“It’s just like you always suspected. Everything is vibrating and everything

is listening. Everything is recording and if you have the right equipment

you can play it all back. More or less.”

—Laurie Anderson

For fans of Laurie Anderson, and I certainly count myself as one, the book Everything I Lost in the Flood archives her forty-plus-year art career, beginning with a 1974 performance piece called Duets on Ice. This work, even in its simplicity, constellates a certain inscrutable attitude in the artist’s relationship with performance, technology, space, time, and presence. In this case, it was Anderson’s waifish persona in Genoa, Italy, as she stood on a block of ice with skates on and played a violin that had a built-in speaker; it was, in her words, “a self-playing violin. Half the music was on tape, coming out of the violin. The other half was played simultaneously, live.” The performance was over when the ice melted. Anderson stood at the Porta Soprana Gate—an architectural artifact conceptually important to her piece in that it commemorated the birthplace of Christopher Columbus, who, after all, had connected the Americas to Europe in a kind of Renaissance, early imperialist coup d’état. I think about the diminutive Anderson in that very conservative northern Italian city, in baggy white pants and barrettes in her long hair, looking like a postmodern ragamuffin—not at all the image of a post-punk, internationally acclaimed multi-media whiz kid that she would shortly become.

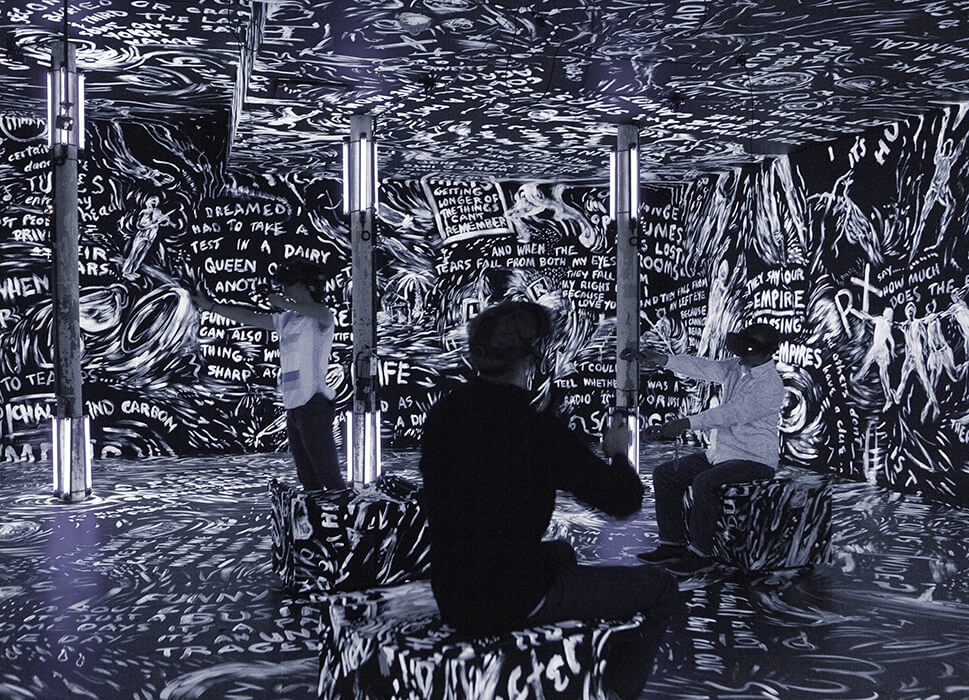

Anderson is a student of history along with being a lover of words and books and the fractal nature of art and language—whether it’s visual, verbal, musical, or a weird system of signs known as ERST (Electronic Reproduction of Spoken Text), a digital code at once visual and abstract. And I suppose the questions that initially surrounded Anderson’s rationale for employing her unusual instruments, her droll, mesmerizing voice, and her uncanny storytelling would be superseded by a critical mass of fame once she made the Pop Charts with “Oh Superman” in the early 1980s. Anderson’s ability to fuse a feral anxiety with wildly fascinating, allegorical content would become a hallmark of her process. And although I would never call what Anderson creates “entertainment” per se—is reading Moby Dick a form of entertainment?—she has the ability to hold an audience enthralled and direct its attention to the biggest of big pictures: a vast and metaphysical swirling, yet highly orchestrated canvas punctuated with metaphors regarding the cycles of life, death, loss, and love—our essential Bardo state that accompanies us from our birth to our last breath. Anderson’s exquisite movie, Heart of a Dog, from 2015, is a deeply affecting meditation about her own essential Bardo-ness wrapping and unwrapping itself around her, from near-death experiences as a child to states of unconditional love—for her dog Lollabelle, for example, and her late husband, Lou Reed. So the history of Anderson’s art making is the history of her elliptical existential journeys, one after another, inquiring always what it means to be human and how best to tell stories about our collective Fate.

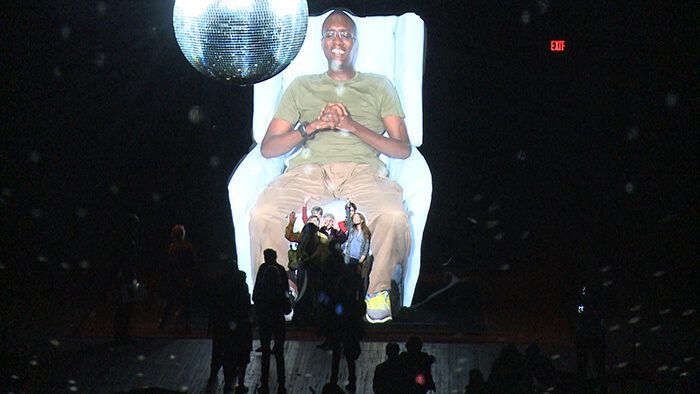

As the first (and the last) artist-in-residence for NASA in the early aughts, Anderson would wind up creating The End of the Moon (2004), a haunting and intensely melancholy work. Here, Big Science got kneaded into a lethal lumpy dough of shock and awe as she layered her impressions of the art and science dyad into the realities of living in lower Manhattan during and after 9/11, followed by the reckoning with a post-9/11 American zeitgeist. In this new world order assigned to us, Anderson suggests we will now live in a complex psychological and philosophical state for the foreseeable future, conditioned by the falling ashes of vigilance and nearly unendurable regret. Apropos to 9/11 and its aftermath comes one of Anderson’s more recent pieces, Habeas Corpus. It represents a stunning crossroads of crime, punishment, and the near ruin of one young man’s life in Guantanamo Bay detention camp: Mohammed el Gharani, falsely accused as a terrorist. The truth is he was eleven years old when al Qaeda struck the Twin Towers. One aspect of Habeas Corpus was the live streaming projections of el Gharani from his post-imprisonment but stateless exile in West Africa into the cavernous space of the Park Avenue Armory in New York.

The depth of Anderson’s beguiling visions and the breadth of her talents as writer, storyteller, musician, installation artist, illustrator, filmmaker, electronic wizard, philosopher, and entrepreneur of dream bodies—all of these incarnations carry the reality of Laurie Anderson, sinking and swimming in the ethos, with all of her genius intact.