Albuquerque Museum, Albuquerque

Dec 1, 2018 – Summer 2019

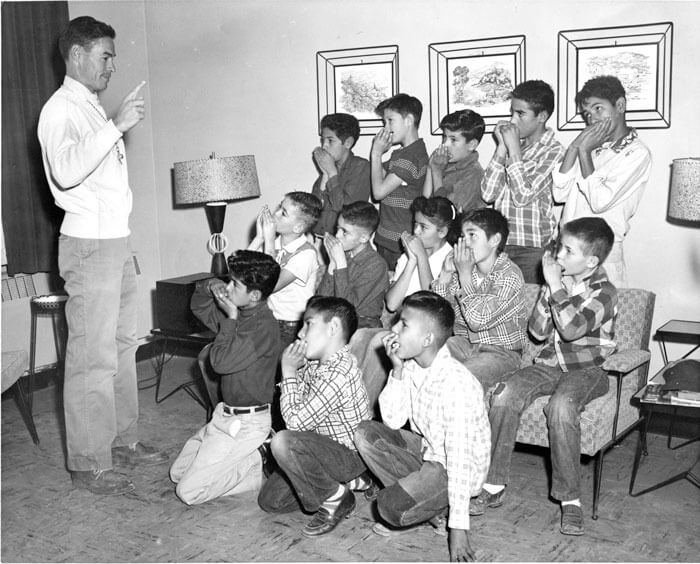

The photos in Everyday People: The Photography of Clarence E. Redman at the Albuquerque Museum remind me of essayist Joan Didion’s ability to remove herself from her stories. In her recountings of discussions between Hollywood stars and their directors, she is completely absent from the room. Likewise, C.E. Redman’s photos, though mostly posed, have a way of disappearing the photographer and camera. These are slice-of-life images of Albuquerque in the 1940s and ’50s, portraits of people and ways of life that continued long before and after there was a camera in front of them.

Redman lived in Albuquerque with his wife Bess from 1930 until his death in 1970. He worked for three years at the Ward Hicks Advertising Agency, where he began shooting photos for his ads, honing the craft that would become his life’s work. In 1933 he opened his own commercial photography studio, where he captured images of weddings, anniversaries, graduations, and other big and small events throughout the city.

Redman took photos of mechanics working in their garages, Future Farmers of America members posing with their prized steer, rodeo queen contestants, and soldiers purchasing postcards and candy at the Kirtland Field Post Exchange. His photos captured everyday moments of a way of life that’s now largely defunct—or changed so much that it’s unrecognizable. Although his choice of subject doesn’t often reflect the racial diversity of Albuquerque’s population, especially the huge number of Native Americans who live here, his lens did turn to working class and white-collar subjects fairly equally.

These prints are working photos: tight crops all around, with the occasional editing mark still visible, reminding Redman to change the developing time or aperture. The anthropological value of these photos only becomes apparent in retrospect, when we want to know how people filled their days without smartphones or the twenty-four-hour news cycle.

A photo called Three girls work a booth at a community health fair (1958) shows three middle- school-age girls standing behind a table filled with fruits and print materials about healthy eating—the girl on the right smiles sheepishly, her arm across her waist, clutching her side in an awkward gesture. The other two girls smile with what looks like genuine comfort. Although we don’t know what story or ad this photo was printed with at the time, there is a story simply in the look of teenage body discomfort presented here. In the context of this event centered on diet and health, all sorts of stories can be read into this girl’s unease. It’s a reminder that some things change and some remain exactly the same.

One photo in the series stands out, simply because the subject is so personal. Jean Redman dips her toe into the water at Ernie Pyle Beach is the caption—Jean Redman was C.E.’s daughter, and Ernie Pyle Beach is now Tingley Beach, the little lake by the Bosque Trail that’s now stocked with trout. The setting is so familiar to most Burqueños, but the curly-haired young woman in a striped bathing dress is certainly of another era. Jean gives a wry smile down into the dark water as she dips her toe in, a “leave me alone, dad” expression.

In Getting ready for the circus (1950) we see one man applying face paint to a younger man, both of them white. I do a double take at this photo and wonder at the context that I cannot see: Is that… blackface? The paint that he’s applying is black, but there’s too little of it to know if it’s going to become a full mask or just part of more a innocuous clown mask. More questions follow: If it is blackface, did Redman know when he started shooting? Did he end up actually using this shot in some publication or promotional material? If he did, does that use imply that he condoned the practice? There are only so many questions that an archive can answer, and the rest have to hang in the air, reminding us that some things have changed—but perhaps not enough.