Diné artist, writer, and educator Brendan Basham approaches writing as he does life: as a process of transformation.

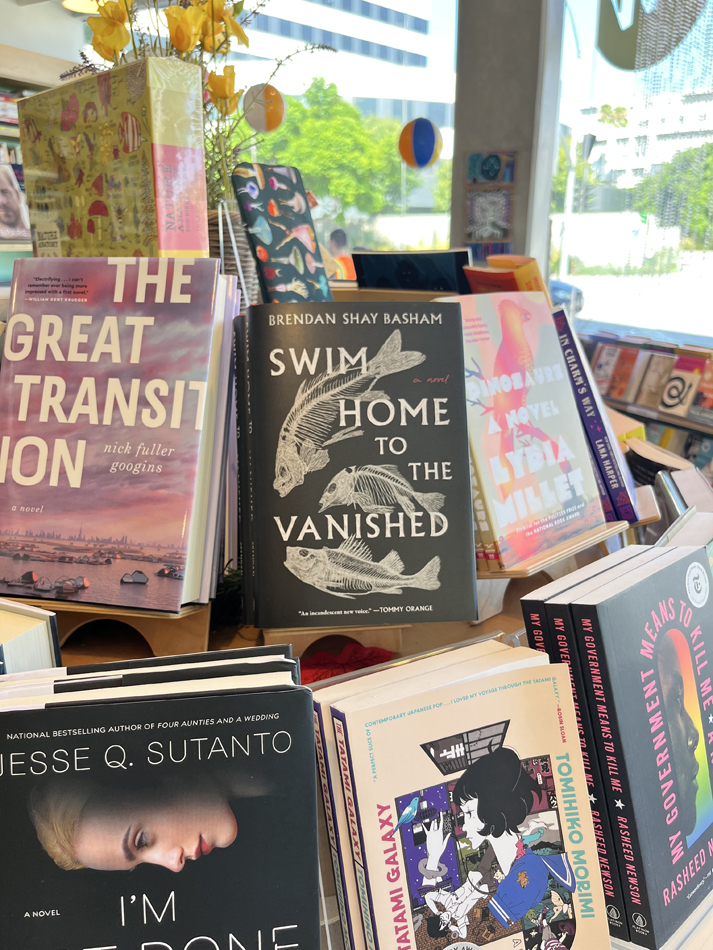

Words can provide a scaffolding for experience—novels, entire homes. For New Mexico-based writer Brendan Basham (Diné), a book begins with a feeling. In the case of his debut novel, Swim Home to the Vanished, which HarperCollins released last fall, two words encapsulated the feelings he wanted to write into.

“I was obsessed with the [Portuguese] word saudade,” Basham says, which “is this extreme sadness with no equivalent in English. It’s like a longing for something you can’t get.” Similarly, the Welsh word hiraeth means “to miss your home because it no longer exists, or never existed in the first place.” Curious about synonyms in Navajo, Basham learned the word ch’ééná from his aunt, who said it was rooted in the experience of the Long Walk. It describes the depression of having lost your home, or the feeling of returning home only to discover it is no longer yours.

Though he’s grappled with a feeling of displacement for a long time, Basham isn’t searching for home, exactly. He has come to understand his travels as integral to the person he is—a feature of his life, not a symptom. Basham was born in Alaska and raised in Northern Arizona and has lived in New Mexico (where he received his MFA from the Institute of American Indian Arts), Washington, Oregon, and Maryland. For Basham, moving and traveling is a process of collection—of community-building—and writing provides a mechanism for synthesis and reflection.

“A novel is a great place to explore and slow down, and slowly fold it all together,” Basham explains. An artist, educator, and former chef, he has an array of anecdotes to contemplate, and he reaches easily for sourdough as a metaphor for his artmaking. “You have to let it rise, garment, and build its own culture. Then you have to punch it down, fold it, flip it, let it rise again. Forget about it.”

Swim Home to the Vanished is equal parts autobiographical and fantastical. Shortly after the death of his younger brother by apparent suicide, Basham moved to Puerto Rico, where he spent years working as a chef. The loss of his brother and his time in the kitchen informs a lot of the novel’s content. In the book, the protagonist, Damien, is indeed a chef reeling after the death of his brother, but his grief has physical qualities beyond the norm: as he mourns, he turns into a fish.

Basham sees this magical realism as a true representation of grief. “I loved thinking about memory, and the fragmentation process of it,” Basham explains. “When we grieve, we lose parts of that memory, or we rewrite it. And our bodies remember differently than our brains do,” he continues. “That’s why I equated grief to the transmutation into a fish, or the losing of a limb.”

Alchemy is essential to cooking, and to writing. For Basham, writing is an act of transmutation; in his work, he combines images and multiple languages to create new forms. “Using a noun to represent something other than it is is a really wonderful thing. That’s what metaphor is all about. I love the idea of giving nouns that much power. Like a limb—a limb isn’t a limb unless you define it. It’s grief, or it’s your brother.”

His latest project—a novel still in its early days—started as an emotional response to the socio-political landscape of the Trump presidency. “I wish I could be the guy who could burn things down,” Basham says, “but I’m a writer, so I can make the guy who can do that. It’s a bit of a vengeance story. It’s about an Indian who’s come to his senses.”

A variety of sources and senses figure prominently in Basham’s writing. In Swim Home, Basham focuses on smell. “It’s a memory sense. It’s the closest sense we have for recall,” he says. Humans have developed predominantly visual cultures, but “marginal” writing, as Basham sees it, invokes more senses, using them to create a hybrid language to describe experience. “Playing with verbs—like using a noun as a verb, synesthesia. It’s kind of another neurodivergence.”

In this way, Basham understands language as generative, not just descriptive. “I’ve always thought my clan name, Tó Ts’ohnii, meant ‘big water,’ and I was attracted to rivers and lakes, and oceans,” he explains. “What I learned later, though, is that it’s not ‘big water,’ but ‘expansive water,’ which is so different. That little idea of shifting the meaning of one word, one idea, can change the way I think about myself and about my own brain.”

But how do we stay in this generative space, and sidestep the categorical constraints of language? Basham considers this, and chuckles drily. “Constant change.”