Del Harrow, a Colorado-based ceramicist, combines ancient practices and contemporary technologies to create historically informed objects that tell stories informing a more sustainable future.

It’s all in the name. Del Harrow’s Instagram handle, parametric_pottery, is a fusion of two halves. On one hand, “parametric”—a reference to parametric modeling, a computer-based methodology borrowed from architecture; on the other, “pottery”—an ancient craft of molding clay, shaping earth. Each is integral to Harrow’s practice as an artist and teacher.

When Harrow, who is represented by Harvey Preston Gallery in Aspen, Colorado, and Haw Contemporary in Kansas City, Missouri, first started exploring the relationship between clay and computer in 2007, there was a lot more optimism around developing technologies. “People thought new digital processes would help us solve problems of sustainability and facilitate biomimicry in design,” the Fort Collins, Colorado-based artist recalls. “But A.I. has opened this whole other complexity. The thing about A.I. that feels destructive is disembodied intelligence.” In other words, it doesn’t have any of the physical restrictions that come along with human bodies, “Like fear of death, or the empathy that comes from the fear of your actions,” Harrow explains.

Harrow’s work is a kind of panacea for our digital age, a model of coexistence between human and machine. Computer-aided design is a key feature of Harrow’s creative and professional practices—he’s a professor of sculpture, digital fabrication, and ceramics at Colorado State University alongside his wife, the potter Sanam Emami—but all his work is grounded in form. “Even when I’m using computer-controlled design, I also have a process using the hand, using craft, the embodied labor of making,” Harrow says. Computer and clay are always in conversation.

Harrow’s sculptures have animate qualities, some more obvious than others. “[When we look at sculpture], we’re trying to experience in an empathetic way what it would be like to make a thing—we can almost feel it in our bodies,” Harrow says. Take the Matrix series, which are computer-generated isosurfaces—three-dimensional visualizations of values—rendered meticulously by hand. They look like fleshy conduits, passageways cut through the earth, or the body. The right angles add palpable tension: clay wants to be stretched, but a vertical sculpture requires structural integrity, too.

Harrow’s latest exhibition, No Ideas but in Things at Haw Contemporary, explores this tension between material and idea. “There was a feeling at this opening that people were really looking at all of the parts, knowing they make sense, but they couldn’t quite describe why,” says Harrow, who has his own thesis. “I see [my work] as a touchstone. When you come to it, you realize, I am in my body. These are my hands.”

Inspired by object-oriented ontology—which regards an object as a thing in its own right, not just relative to human beings—Harrow challenges the typical hierarchies of methods and materials. He describes the three years that went into the show as a process of organic accumulation.

“Often the individual parts [of the show] came out of simple, fragmentary ideas,” he says. “These are the practical things that get [me] to the studio: what material do I have on hand, what am I gonna do today? Through the process of making that form—asking questions about the form type, the material—the form branches and connects to others.” The finished objects, then, were something of a surprise.

The first room of the show includes two wall-mounted, plywood cabinets filled with small objects that echo some of the large pieces in form and color.

“They’re a collection of the material debris from making all the other work in the show. I would give myself the rule: there’s a pile of scrap, I’m going to quickly turn it into an object. Then I would glaze and fire it along with the other work.” The cabinets reflect the show’s organizing principle, or central line of questioning: What exactly are these things? Are they art objects, or refuse? Are they intentional, or accidental?

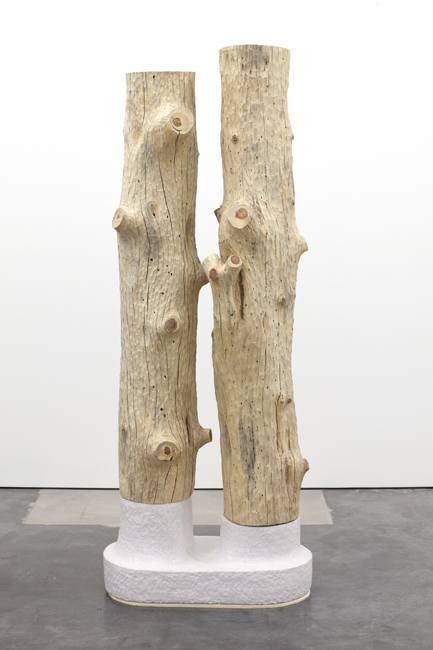

These questions extend across the show. The pine used in the bench pieces was essentially rubble from Harrow’s studio construction project in Colorado—the felled tree sat outside, slowly rotting, for years before Harrow started experimenting with pieces from it. The primacy of the object is clear: the viewer experiences each element of the show, however it came to be, as art.

Lately, Harrow has spent more time among the scraps, considering the items and information we discard. His current project, The Ceramic Materials Atlas, is an interactive website following the myriad paths industrial materials take to get from their origins to the end user.

“This started as a mapping project, but now it’s more like a storytelling project,” Harrow says. Atlas includes about fifty-odd materials common to the pottery studio, like feldspars from South Dakota and Canada, or barium carbonate, which accounts for the emerald green sheen on Artemis, another wall-mounted piece in the Haw Contemporary show. Artemis (2023) is a series of tiles patterned with digitally-made molds and hand-cut textures, then coated with the vibrant barium glaze—it looks like a wall of leaves. Harrow has traced his barium back to an open-pit mine in Bulgaria, where it is the byproduct of a steel refinery. “Barium is coming out of a tailings pond,” Harrow says. This gem-like sheen comes from waste sludge.

With Atlas, Harrow aims to elevate a material’s story—its history—to the same level as its function or presentation. “There are lots of materials we have aesthetic responses to that are complicated by ethical understandings of their origins,” he says. “I’m thinking about diamonds or animal fur. The hope with this project is that we add these layers of meaning to other materials with which we don’t tend to experience complexities or conflicts.” Harrow probes: what is the role of the artist in the global economy? How should an artist consider sustainability and social justice within the context of their material choices?

A material’s fraught history doesn’t necessarily mean artists should stop using it. Regardless of intentions, this doesn’t always have the desired effect.

“Even if every artist stopped using cobalt, we’d continue to mine it at the same scale,” says Harrow about the material—it’s the metal that helps the lithium-ion rechargeable batteries in laptops and cell phones stay powered up, and it’s been mined to disastrous effects in the Congo. Instead, Harrow says, “Adding depth to the way we collectively apprehend the material”—complicating one-dimensional narratives—“is the most generative and potentially positive way we [as artists] can contribute.”

The question of intention, which is so prevalent in discussions of technology’s role in art-making, obsesses Harrow. “When we’re working on something, there’s the thing we think we’re working on, and then there’s the thing happening in the margins,” Harrow says, chuckling drily. “Maybe the thing is the margins is the actual thing.”