BOOKS AS EXHIBITIONS

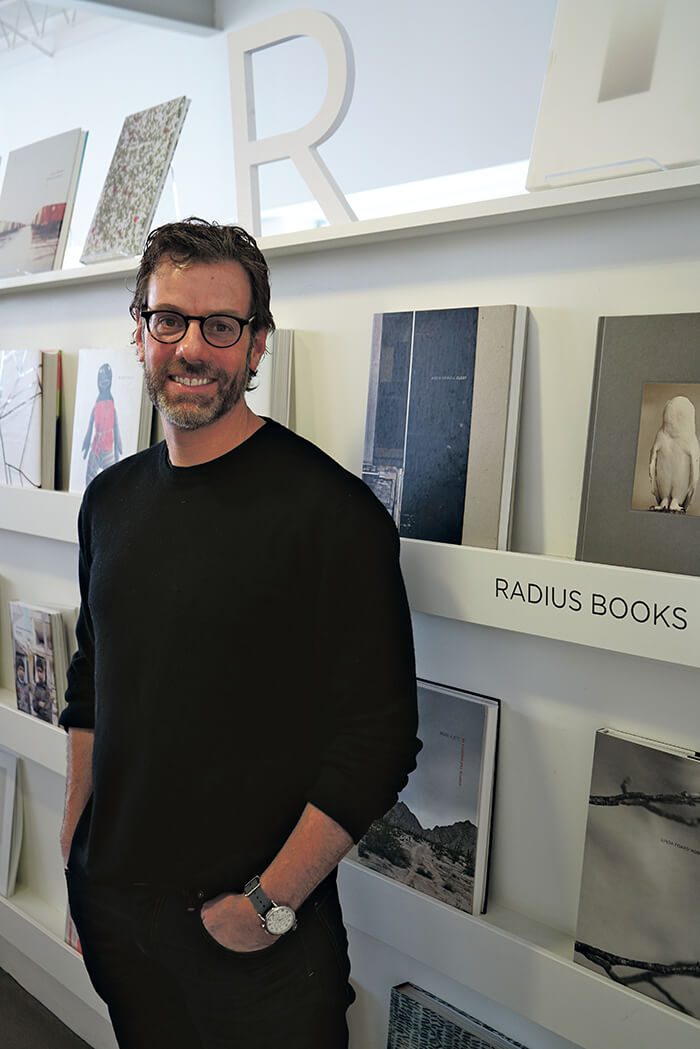

“We do this bookstore every December,” says David Chickey. He stands in the lofty, second floor office of Radius Books on Palace Avenue, a rare example of midcentury modern architecture in Santa Fe. On one end of the open floor plan, Chickey maintains a project space that currently houses a vast museum of books designed by the nonprofit publishing house. “Every one of them has quite a long story,” he points out, touching one of Radius’s covers.

A little over 25 years ago, Chickey was working for Sotheby’s in London when he visited Santa Fe for a friend’s wedding. The bride was determined to set him up with another guest, Trey Jordan. “It was a recipe for disaster,” says Chickey. Jordan had recently earned his architecture degree in New York and was looking for a new place to launch his career. Chickey is originally from Nashville, and Jordan is from Galveston, Texas, and grew up visiting Santa Fe.

They returned to the city where they met in 1991. Jordan opened an architecture firm, and Chickey tapped his art world connections to launch a for-profit graphic design business.

“We figured out in our 20’s how to build a life here,” says Chickey, strolling past Jordan’s sector of their shared office (Trey Jordan Architecture) and into a small kitchen. “When I started my design office and most of my clients were in New York, it was actually to my benefit to be here and travel there. I was only available for 3 or 4 days at a time, so you couldn’t put me off until next week.” For anyone who collaborates with artists—or New Yorkers—that’s a definite advantage.

One project led to another: Chickey would design an artist book, and catch the eye of a gallery or museum where the artist was showing. He made monographs and catalogues, signage and business cards. It was the perfect environment for his curatorial and design skills to organically merge. “I took it as my mission to make a book that’s similar to a museum exhibition,” Chickey says. “An exhibition should be the best reflection of what an artist does. A book can do the same thing.”

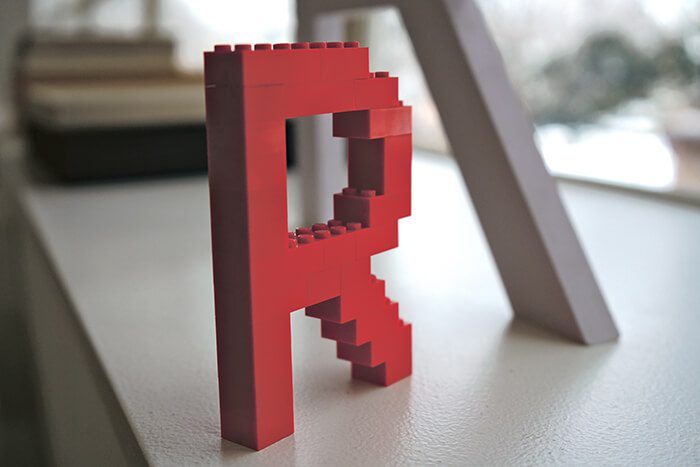

Chickey pours some coffee and quiets down his three rescue dogs, who have gathered around his feet. His philosophy of design unspools over the next hour, and it’s dotted with surprising comparisons. In Chickey’s mind, books are highly portable art exhibitions without a closing date, but they’re also canaries in a coal mine, organisms that change and grow; they are alsoart objects in their own right. “Our books are pushing the envelope of what a book can be,” he says.

BOOKS AS CANARIES

Years ago, a publishing company contracted Chickey to work with a Barcelona-based photographer who’d recently completed a project in Mexico City. “She had photographed these gardens that were burial sites,” he says. “They had a checkered history of complicated sociopolitical situations, where people had been put into open graves.” These sites of tragedy and horror had slowly transformed into lush green sanctuaries, a tribute to nature’s healing power.

“Complicated work, right?” Chickey says. He and the artist were shocked when the publisher suggested reaching out to Martha Stewart to write text for the book. “They thought she would really respond to the nature and the landscape,” he says. “This was borne out of nothing more than the idea that they’d get more press and sell more copies.”

Chickey felt the pressure of the publisher—he estimates that large imprints must sell 3,000 copies of a book to break even—but he wondered if there was a better way to serve artists and readers without having to sell out. At a publishing seminar, he learned that audience demographics for art books were rapidly narrowing. “If libraries were having budget squeezes, it was easier to cut out the expensive books than it was to cut out everything,” Chickey says. “[Art books] were the first to go. It was the canary in the coal mine, to some degree.”

If well-heeled art collectors were the only people buying art books, what was their contemporary significance? “That’s a pretty small world,” says Chickey. “I wondered if I could put this into a different model, and deliver it to an unlimited audience.” In 2007, he launched the nonprofit company Radius Books—and freed the canary.

BOOKS AS ORGANISMS

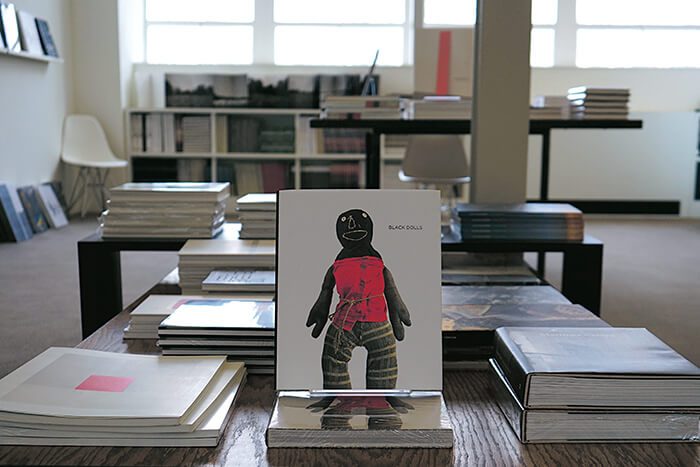

Chickey still runs his for-profit design firm along with Radius Books, working with a small team (currently, four employees and an intern) to produce hundreds of books. In both endeavors, the books are for sale online and in bookstores and museums. Through Radius, Chickey also donates art books to underfunded libraries, schools and literacy programs across the country. As the nonprofit approaches its 10th anniversary this fall, Chickey says they’ve given away over 50,000 books.

“It’s about trying to be accessible to as many audiences as possible,” says Chickey. “It’s important that people are buying them as well as being given them, because that legitimizes everything about the books in a broader sense. We didn’t do this so we could exclude one audience or another.” At first, Chickey was nervous that libraries might not consider art books a priority, but the program has been wildly successful. A librarian from Albuquerque called Chickey after an early round of donations, and told him that an art book hadn’t been added to the entire Albuquerque library system for over eight years.

Whether he’s wearing his for-profit or nonprofit hat, Chickey fiercely upholds a transmutational philosophy of design. The books often take between one and four years to complete, and by the end he has analyzed the narrative purpose of each and every design choice. “If you inhabit the art and spend time with the artist at their studio, or you’re with the estate or museum, things start to naturally evolve,” Chickey says. “You need to let that happen.”

In 2013, Radius published a volume on the artworks of Rudolf de Crignis, a New York abstract painter who died tragically in 2006 at 58 years old. “Mr. de Crignis made seemingly monochrome paintings, often in radiant blues or subtle grays, built up from numerous thin layers of different colors,” wrote Roberta Smith in his New York Times obituary. His works possess the alchemical power of Mark Rothko’s black paintings in Houston’s Rothko Chapel, with surprising hues emerging as the viewer’s perception subtly shifts over time.

This is a notoriously tricky effect to capture in a printed reproduction, but Chickey was determined to discover a design solution. “I back printed the title on the jacket, so it just looks like grey type on a minimalist cover,” he says. “But if you spend some time looking at it, each one of the letters starts to glow in a very subtle, different way that’s totally reflective of that.”

Contemporary graphic design leans heavily on digital technologies, but Chickey’s process is surprisingly tactile. He runs his fingers over every material, and prints countless proofs of each project to review it in the physical world. “Each book should have this environmental, experiential quality. What are ways in which we can expand on this idea of what an artist does?” he says.

BOOKS AS ART

As a project approaches completion, Chickey travels to Italy to meet with his printers. He’s worked with presses across the world, from Iceland to Singapore, but there’s nothing quite like a European bookmaker. “Italy and Germany have, essentially, the longest history of putting ink on paper,” he points out.

Even for the finest press, Chickey’s requests can be challenging. “A few years ago, we worked with an artist who had done these incredible images of plastic floaty toys in Hawaii,” he says. “That artificial color was an inspiration for her in terms of how she made images.” Chickey went to an Italian bookbindery in search of a plastic material that could hypostatize the artist’s color theory.

“They’re used to me now. I have a reputation for this,” says Chickey. “I said, ‘I want a jacket material that will be durable, but I want it to look like you cut it from a plastic raft.’” After a long hunt, they finally found a workable material with the semi-transparent quality that he pursued.

Chickey’s innovations extend far deeper than his book’s covers. He’s created inserts, foldouts, pockets and myriad other elements in service of his collaborators’ creative visions. Among his high profile collaborators are Lee Friedlander, Marlene Dumas, and Doug Wheeler. I ask Chickey if he considers his books to be sculptures. His immediate answer is an effusive “yes,” but then he adds a caveat. “There’s an economic reality here, too,” he says. “There are artists who make books that are one-of-a-kind, handmade objects. What we do is slightly different in that we’re making an object that’s meant to go to a mass audience. We have to figure out ways to do that affordably, and make it go out into the world.”

Last February, a profile on Chickey appeared in the Wall Street Journal. His grammar school art teacher, Rose Pickle, saw the piece and contacted him. “She’s taught at that school for 40 years,” he says. “She said, ‘I always wondered what happened to you. I knew you would do something in the art world.’” He returned to his hometown of Nashville last fall to be a guest lecturer in several of Pickle’s classes. Her students were surprised to hear that you could still make a living in the publishing industry, but the real breakthrough occurred when Chickey encouraged them to look through his books at the end of class.

“They were all so into holding the books and looking through them, they didn’t want to go to the next class,” Chickey says. “We still love books, and crave them, and like touching them. They carry a certain power.”