Early in her artistic career, Daisy Quezada came across a real-life scene with all the power of an omen. She and her mother had ventured to their old house in Jalisco, Mexico, which was long abandoned. They leapt across the tall stepping-stones in the enclosed yard outside—formerly a pigpen—and found the interior ransacked. It was common for people to hide money and valuables in the walls or floors of their homes, so strangers had torn the place apart in the time since the family moved back to the United States.

In a tiny second-floor room, among scattered family photos and upended furniture, was her mother’s bright pink quinceañera dress piled atop a chest and illuminated by a narrow glass skylight. This accidental art installation with all its intrinsic symbolism—of presence and absence, ceremony and desecration, home and departure—would make an indelible mark on Quezada’s aesthetic vocabulary.

Seven years later, Quezada ushers me through her Santa Fe home and into her garage, where ghostly white porcelain forms shaped like blouses, t-shirts, and pants hang from various objects and surfaces. The artist uses an adapted lace draping technique to manipulate garments culled from her own closet or donated by people on either side of the U.S.-Mexico border. She coats the clothes in porcelain slip to freeze their folds in place and fires them in a kiln so that the fibers burn away but the fine details of the garments are preserved in clay.

Quezada pairs these sculptures with found objects from the borderlands (gardening tools, shipping crates, salvaged sections of the border fence). The combinations she creates are loaded with the complex personal, cultural, and political meanings that this connected-but-divided region endlessly generates. She encourages me to pick up one of the finished ceramics, and it feels heavier than I expect but fragile as an eggshell. I realize I’m holding my breath, as though a life is in my hands.

You were born in California in 1990 to immigrant parents and moved back to Mexico as a small child. Did you understand what the border was during that move?

I just understood that it was a huge divide. I remember our drive going down there being really intense and having to be planned out extensively. The back seat of the truck was packed with four or five people, and it was raised with a board, so we could shove everything we could underneath. It was really strange to have all of these bodies lined up. I remember it being really hard—and really stinky because sometimes our stomachs got upset. It was extremely hot.

What did you find on the other side?

As soon as we got to Mexico, it was an amazing place to be. I felt free. I went to school in Jalisco for a little bit, to pre-kindergarten. My parents were working the farms, so my mom sent us to this teacher to keep us entertained. I don’t remember the actual school, but the journey of getting there. I was terrified of cows, and I had to go over this huge rock wall and there was a bull there. Cows and bulls don’t like me, so they would chase me. I remember running to get to the other wall and jumping over that, because the bull couldn’t get through it.

So there were lots of adventures—and misadventures, which can be just as good in retrospect.

I still think of it as that kind of place. There’s just something about the earth there and the sky there. The arroyo is beautiful; the mountains there are great; the food that we grow in the ground is so good. I miss it a lot. If I lived there and had to eat beans every day, it would be perfect. I would never be upset. In the U.S., things are just “go, go, go.” You have to get things done; you have to keep the momentum going.

If I lived [in Mexico] and had to eat beans every day, it would be perfect.

Your family moved back to the United States so that you and your two sisters could attend school here, and you lived between southern New Mexico and Arizona. Do you remember learning about border issues in school?

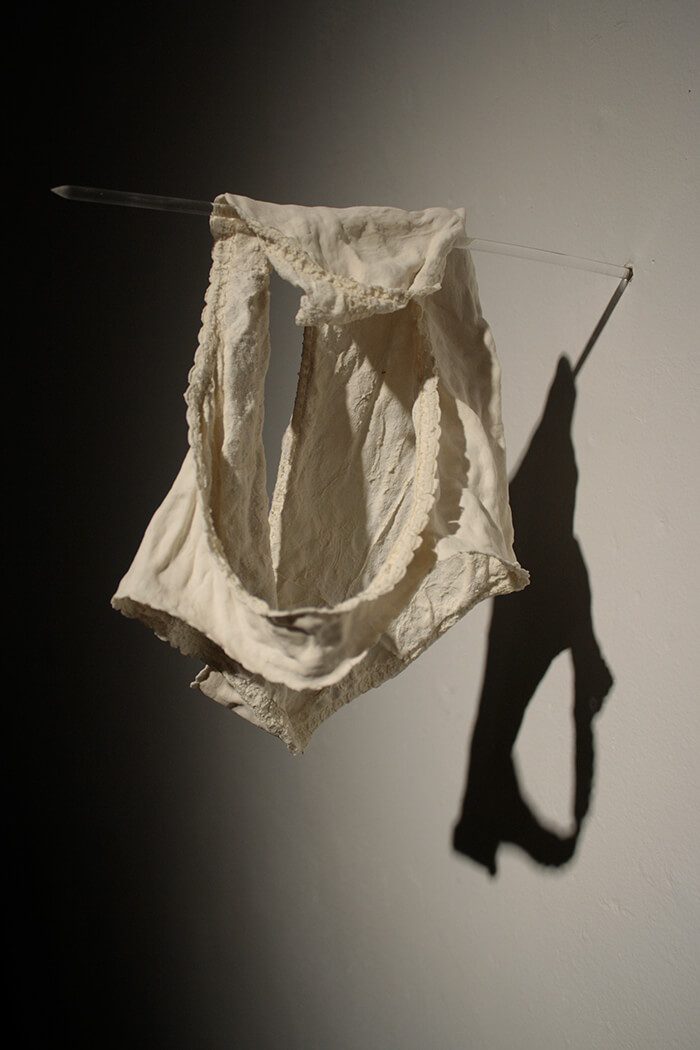

In high school, in Tucson, there was this activist guy that came into Mr. Leon’s class, and he was talking about the rape trees [in the Sonoran Desert], where the coyotes would split up the men and women. They would rape the women and hang their panties in a tree. I ended up making a piece on the rape trees when I was in graduate school, and I went back to old drawings that I did in high school. Even at that time, I was trying to process that story through art.

2014, porcelain in Sonoran Desert.

College of Santa Fe was in its final year when you enrolled there on a tennis scholarship, and then you returned the next year when it became Santa Fe University of Art and Design (SFUAD). What was the focus of your undergraduate studies?

I was doing studio arts and was interested in sculpture at the time. I remember meeting Susan York my freshman year at College of Santa Fe. I was in the ceramics studio doing some project that I was trying to finish up. She didn’t know who I was, and I didn’t know who she was. She said, “You know, you can do this technique, and it’ll give you the effect that you want. It’s much easier.” After I left New Mexico for grad school, I came back to SFUAD, and Susan York and Tom Miller pretty much pushed me and gave me the motivation I needed to keep going.

I couldn’t bring the dress back, because that’s where it needed to be. I didn’t have a right to take it out of that space.

What ideas were you exploring as an undergraduate?

That’s where I started more on personal identity. I was having rich memories of me and my mom walking through her childhood home back in Jalisco. When we found my mom’s quinceañera dress, she said, “That was the first article of clothing that actually belonged to me, that wasn’t passed down.” It was amazing, the stories and emotions that were being shared. I couldn’t bring the dress back, because that’s where it needed to be. I didn’t have a right to take it out of that space. My mom had three photos of herself in this dress, so we sat in her kitchen with my dad, and we recreated the dress. We measured it on my body, and that became the first large-scale porcelain piece I made. I finished it right as I was graduating. It had a huge impact on me, that piece, and it carried on through all of my work.

After completing your BFA, you got a full scholarship for the MFA program at the University of Delaware. In past interviews, you’ve talked about how difficult that time was for you.

I went out there, and it was a huge culture shock. I had never been out East—that was the first time—and it was really strange to me to experience people’s understanding—or lack of understanding—of the border and what takes place. I remember having to explain what coyotes were. There wasn’t anywhere to speak Spanish there, and I remember constantly being categorized as “the Mexican.” No one actually said that, but I felt it.

I think the border doesn’t stop at the exact division that’s parting us, but it spans further and absorbs and consumes everything. It’s not necessarily even New Mexico; it could be out in Delaware.

I was really isolated there, so I had a need to connect back. I was reaching to try to understand the relationship between where I was and where I was from. I started making the rape tree works, the Árbol de Violencia series, which were undergarments hanging on acrylic rods. Then I started making these coffin pieces with garments and raised segments of soil, thinking about the burial of individuals during the femicide in Ciudad Juárez. The idea was to raise up soil so that it would obstruct someone’s path, so they couldn’t just walk past it or over it. So I was really expanding from telling just personal stories to working with other people and looking at these larger issues.

Were you able to find that connection, between the East Coast and the Southwest?

I think the border doesn’t stop at the exact division that’s parting us, but it spans further and absorbs and consumes everything. It’s not necessarily even New Mexico; it could be out in Delaware. Even in places where we’re not literally butting up against Mexico itself, we still are.

[My work] expanded much more when I removed myself from what some people call our safe zone. I took myself completely out of what I felt to be a secure and comfortable space and placed myself in this environment where we didn’t necessarily share the same customs, traditions, or philosophy. It kind of woke me up a bit more. I feel like I need to do that again to myself, as uncomfortable as it is.

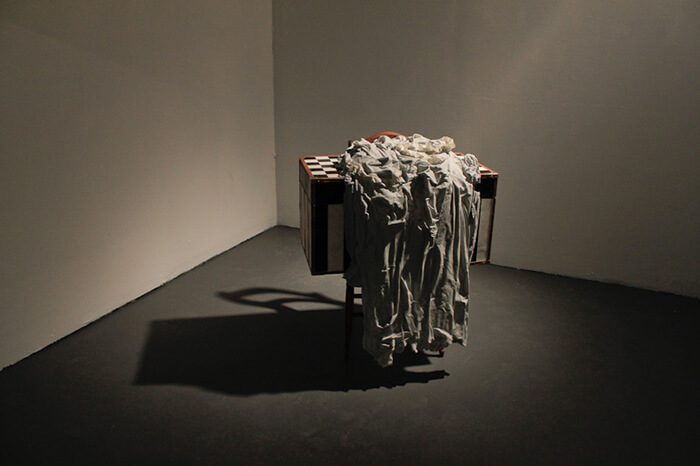

2017, porcelain, concrete, metal, cardboard, & audio, Photo by Jeff Well. Courtesy the Denver Art Museum.

You moved back to Santa Fe in 2014. Since then, you’ve worked at SFUAD in various roles, exhibited in major shows regionally and internationally, completed a residency at Santa Fe Art Institute, and received a Fulcrum Fund grant. You’ve engaged a lot with public school kids throughout this time, gathering garments and stories. Tell me about that process.

For this group show, Mi Tierra, at the Denver Art Museum [in 2017], I was working with youth in Santa Fe and Aurora, Colorado. They donated articles of clothing that belonged to them or their families. Some of them couldn’t afford to donate a full article, so it was scraps or segments of pieces that they cherished very much. It was a huge trust thing, because you can’t recover the original articles at the end of the process.

I wanted to get to know them and learn their stories, so I wasn’t just an individual going into a community, gathering stuff, and then abandoning them. Before the opening at DAM, I wanted to make sure they were aware of what happened with the pieces and how they were in conversation with other works in the show. After the show ended, I actually gave each student the piece that I made from their article.

It’s a good way to approach these big, complicated issues in the borderlands. You always start with individual stories.

I feel like that’s the easiest way of understanding it. If you try to relate to people and what they’re experiencing, that’s a read directly on what’s happening, how it’s affecting them individually. With the students, we’ll tell stories and speak with one another jokingly, and then we’ll get very serious at other times. You can’t just read a paper and assume you know the world and what’s going on. You have to be out there with people and talking to them.

All the individuals that are being affected by policies that are being passed, they are experiencing the same sort of oppression that’s taking place. For me, it’s one person, and it’s a whole at the same time.

You’ve been making larger groupings of the sculptures lately. Are you widening the scope of your storytelling?

I am. I’m interested in what a collective can do, so that’s where I’m going. I’ve been getting upset with how certain people are viewed or perceived. It’s really strange how the media is portraying things [on the border]. It’s distancing what is actually personally happening with these people, and kind of just categorizing them. “Oh, these are just people that came in a caravan.” All the individuals that are being affected by policies that are being passed, they are experiencing the same sort of oppression that’s taking place. For me, it’s one person, and it’s a whole at the same time.

Garments are such a strong representation of that idea.

I feel like the pieces are individuals. It’s articles that we’re carrying, that we’re holding against the body. It is that individual that was imprinted.

You’re working with fiber, but it’s gone by the end of the process. Do you feel like you’re a fiber artist as well as a ceramicist?

I wouldn’t take either of those titles. I would just call myself a sculptor or an installation-based artist. I don’t think I’m a ceramicist by any means. I’m not well-versed enough in functional pottery, in that traditional sense. I don’t think I’ve ever taken a fiber arts course, outside of having a conversation with Jane Lackey.

It does look like a normal, everyday garment, but the strength that it has and the space that it holds is different.

I guess the work hovers at the edge of all these things. It’s hard to categorize, just like people.

With the piece that was at 516 Arts [for the 2018 show The U.S.-Mexico Border: Place, Imagination, and Possibility], people were like, “Oh, look, it’s just a shirt.” After a while, they were like, “Oh, no, this is porcelain.” They could see the imprinting of the embroidery that I had stained on it, so it was really strange for them to have that push and pull. It does look like a normal, everyday garment, but the strength that it has and the space that it holds is different. At least for some people.