Complementing and circumventing traditional gallery relationships, artists in Colorado find financial and material support through corporate and private clients via third-party advisors.

This article is part of our Medium + Support series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 8.

DENVER—A mere thirty seconds spent perusing Crane Watch Denver’s website reveals just how many construction projects the city currently has underway. But who is making the art for these developments? Rising demand for art in commercial and residential spaces has contemporary artists in Colorado supplementing and bypassing gallery management to place their work in office parks, hotel breakfast nooks, and even the metaverse. Leveraging a lesser discussed—yet well-established—system of patronage aided by third-party advisors, artists are cooperating with clients to make and sell works that fit distinct venues and briefs.

In August 2022, Chris Roth, founder and principal of CR Projects, contacted Boulder-based ceramicist Liz Quan to create work for Boulder’s new “high-end” Pearl East Business Park in collaboration with the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art. “It was a big job… one of the biggest jobs I’ve done,” says Quan. Roth, whom she calls “a total advocate,” was Quan’s go-between, facilitating communication with designers, architects, and other project supervisors.

Commissions are often based on previous work and according to Quan, clients either “want something that you’ve done before… or like [that] but three times bigger.” She sketched proposals and met with developers to pinpoint her design, collaborating with Roth to finalize composition, color, and size. Her triptych, Wandering About (2023), was officially installed in May.

“I feel like they’re all different, but of the ones I’ve done, this was unique maybe because of the scale and the investment for [the client],” explains Quan about this assignment. She has recently sent work to Vancouver, British Columbia, created commissioned sculptures for a private home on Lake Michigan, and is currently tackling two other residential projects.

Notably, collaborations like these happen inside and outside conventional gallery relationships. Quan went solo almost two years ago, citing increased management complexity for artists. While not all creatives want to assume complete sale of their work, they are “way more in control of that than they used to be,” she observes. Fees are part of this equation: although “there’s always going to be a middle person,” galleries are more likely to take a larger percentage than an art advisor, says Quan. Plus, “you’re always dictating your price.”

As increased costs of living intersect with artist-as-entrepreneur trends in the Colorado art market, it’s unsurprising that creatives capitalize on various revenue streams, even if their work is usually managed by someone else. Roth says that it’s approximately “a fifty-fifty split” between artists that he collaborates with individually “versus artists whose work I purchase through a gallery.” Regardless, he insists on working directly with creatives to ensure clear communication.

Roth started CR Projects in 2019 and relishes his role because he connects clients with “deserving” artists who make “cool” work. Formerly at Nine dot Arts, one of numerous art consulting firms in Colorado, Roth’s career is built on “cultivation and stewardship of patrons of the arts.” He enjoys being the intermediary, observing that “the two ends of the spectrum don’t always speak each other’s languages.”

Though advisors focus on clients—understanding tastes and needs, facilitating installation within strict budgets and timelines—Roth is motivated to help artists. Misconceptions about what great art is (and can be) affect collecting practices, and Roth’s position helps him “open people up” to expand the breadth of corporate holdings. And he doesn’t just propose artists who’ve completed specific work—Roth also recommends those who might do something new if given the chance.

For Studio B in Aspen and Boulder, a similarly “inclusive” process means sourcing art for everything from appliances to stagings to virtual walk-throughs. According to project architect Sarah Harkins and designer Olivia Kleespies, clients frequently possess existing collections, so design, lighting, and materials are selected with that art in mind even as the firm periodically sources new work for the space. “Artist collaborations have yielded distinctive doors, furniture, custom pieces, and finishes, reflecting diverse creative partnerships aligned with individual client preferences,” says principal Mike Piché. One such collaboration is with multidisciplinary artist Jamie Kripke, whose work was temporarily exhibited during the firm’s Villa H staging.

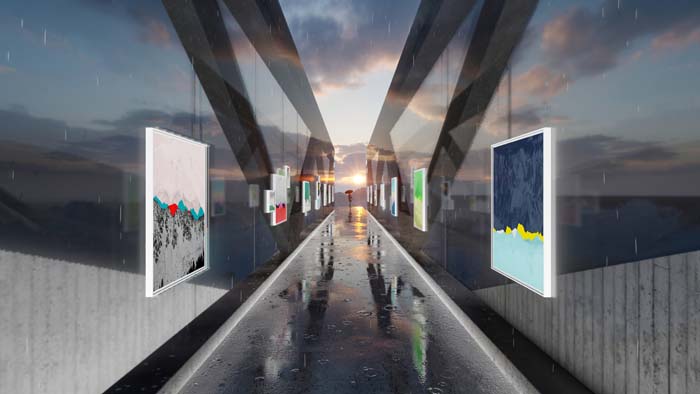

Studio B also utilizes virtual reality as an architectural design tool to support artists, resulting in a metaverse museum of Kripke’s latest collection, The Divide. “As an alternative medium for patrons to experience his latest collection of work,” the museum is also “a step towards shaping how we interact and experience ecommerce, marketplaces, and product presentation,” states the firm. And in Studio B’s framework, virtual reality “allows us to really see how the art will look in relationship to the home when hung in its actual context,” Piché states.

So why now? Though some corporations view art as a “frill,” explains Roth, “others understand the impact it has… and see it as essential to differentiate a space from the competition in the market.” So while developers continue to expand, artists and intermediaries see the opportunity to divert a better percentage of that growth into a cultural sector grappling with affordability, consistency, and funding. Advisor-led patronage won’t cure everything that ails the local art scene (the client comes first after all, and “local” is a relative term), but by connecting potential collectors with new art, this system ensures that artists can get more of what they need in return.