Selective histories have long defined Santa Fe’s main gallery district. Kyle Maier’s digital Canyon Road History project aims to round out the picture.

The scene opens on Cristo Rey Church, seen from a moving car as the road bends, changing from Camino Cabra to East Alameda and dividing Canyon Road in two. The car cruises onto lower Canyon, passing low-slung adobe buildings, wooden fences, spring-green trees, dust blowing in the street. Aside from vintage Fords and retro street signs, the video is difficult to locate in time, and could be from any point during the last seventy-odd years.

But because this is an Instagram Reel, we know from the caption that it’s 1966. The drive is set to the Shins song “New Slang,” a plaintive ode to a fucked-up past. The combined effect of image and song is transporting: for less than thirty seconds, viewers are granted a glimpse of a bygone world that’s also eerily familiar. The range of memories and emotions the clip elicits are reflected in the comments:

“I was baptized at Christo Rey [sic] 1971.”

“I can remember when nothing but Latinos owned their homes on Canon [sic].”

“Lol back when Santa Fe was affordable for real people and artists.”

“Still mad at my Dad for selling our house on acequia madre [sic].”

“Home.”

And, from the author of the post: “nothing has changed and everything has changed.”

The reel is the most popular among dozens of clips and historical photographs spanning more than a century that were rediscovered and curated by Kyle Maier, an Albuquerque-based filmmaker behind the account @canyonroadhistory. Maier, who was born in the 1980s, grew up in Las Cruces and felt no special connection to Canyon Road or Santa Fe until he returned to New Mexico as an adult after living for five years in another history-heavy town, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. He recalls revisiting Canyon, a notorious arts district, for the first time in many years: “A boomer with a gray ponytail told me about how he first came to Santa Fe in 1969 [with] all these hippies,” Maier says. “He painted this bohemian, wild scene in my head. I was awestruck. […] Then a car drove by, a Ferrari or something, and I thought, how does this happen? This doesn’t just happen—what occurred for this intersection of worlds to take place?”

Today, Canyon Road is a tourist hotspot, a commercial gallery district, and one of the largest art markets in the country. Maier notes that since the opening of the Santa Fe Trail in the 1840s, the interest in and demand for New Mexican goods and artwork has only grown.

The images Maier presents are collated from public archives and personal collections. He shares Doug Magnus’s ’70s party reels, Eva Scott Fényes’s late 19th-century views of Atalaya and Picacho peaks, his own contemporary Polaroids. Maier is fascinated by long-held constructs that scaffold our ideas about what Canyon Road is and how it came to be, and committed to interrogating them via interviews and research. The central tenet of his project is that the story collectively told about Canyon Road (via the forces of media, economics, and politics) is incomplete, and it can elide other perspectives that were instrumental in making the street a central player in the ongoing story of American art.

While the History of Canyon Road project is Insta-centric, it’s also continuous, evolving, and multimedia, encompassing a YouTube channel, postcard series with QR codes (that lead to short films on YouTube), and talks put on through the Historic Santa Fe Foundation, Maier’s fiscal sponsor.

In person, Maier is quietly passionate: he speaks with detailed knowledge about his work, but he’s a good listener, too. He’s the kind of guy who strikes up conversations with folks on the street, and a person people trust with their stories. He’s also quick to cite his intellectual forebears (Chris Wilson, author of The Myth of Santa Fe: Creating a Modern Regional Tradition, is a biggie).

Maier characterizes many of his encounters as something like kismet. “Santa Fe kinda grabbed me by the throat,” he says. “It’s been six years now, and things just happen, they fall like dominoes. […] Santa Fe, I give her a lot of credit—it’s a feminine town for me—something about that city, something will land in my lap.” Maier is also gregarious, and it’s served him well.

Santa Fe is both: it’s the renown of the artists who bring their brilliance and contribute to the fabric of the community, and the old-school New Mexico families.

A couple years ago, he recalls admiring artist Fremont Ellis’s former home and studio when the director of the Thaw Charitable Trust, whose office is in the building came outside and they started chatting. Thaw ended up granting Maier $10,000 toward his project, which he used to pay half a dozen collaborators. He’s also received funding from Nedra Matteucci Galleries and the Women’s International Study Center, the nonprofit behind the Acequia Madre house, which was built in the 1920s by Fényes, a wealthy, New York–born patron, photographer, and painter who arrived in 1889.

Few would dispute that history is alive on Canyon, that different eras jostle against the present—a ’70s Chicano mural by Los Artes Guadalupaños de Aztlán sits in the middle of a paid parking lot; the faded lettering for the corner store Gormley’s remains on what’s now Nüart Gallery—but the nature of the past, and whose stories should be told, is contested. In particular, Maier highlights the New Mexico Museum of Art as controlling an outsized share of the narrative.

“The history of the art museum starts [in the 1910s] with Carlos Vierra and Edgar Lee Hewett, Robert Henri, John Sloan, Randall Davey, and Sheldon Parsons,” he says. “It’s a true story. But what they’re doing is selling it as the history of American art in Santa Fe and conflating it with a larger story. […] There was already an art scene. If we don’t look at the 1890s, we miss out on important cultural contributions of people who were here.” Maier also points out that centuries-old arts traditions (from Chimayó weaving to Pueblo pottery to bultos) significantly pre-date the American era, and points to Cristo Rey Church, constructed in 1939 just off Canyon, as a metaphor for collaboration and a case for telling more complex stories.

“John Gaw Meem designed it and that’s all you hear about,” he says. “But Cristo Rey was built by the community. The families volunteered their time and resources and built it with their own hands. Santa Fe is both: it’s the renown of the artists who bring their brilliance and contribute to the fabric of the community, and the old-school New Mexico families. Both are what made Santa Fe a cultural capital of the West, and half of the story isn’t celebrated among institutions.”

One way Maier grounds abstract ideas is exploring how they’re embodied in individuals. He cites Fényes as a personal hero, who he says loved Santa Fe for what it already was, sensed it was on the precipice of creative proliferation, and understood her role in cultivating and documenting the art colony she helped establish.

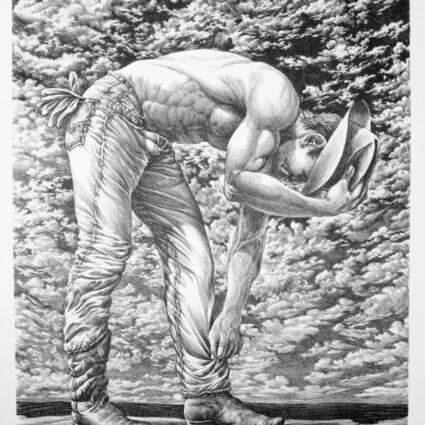

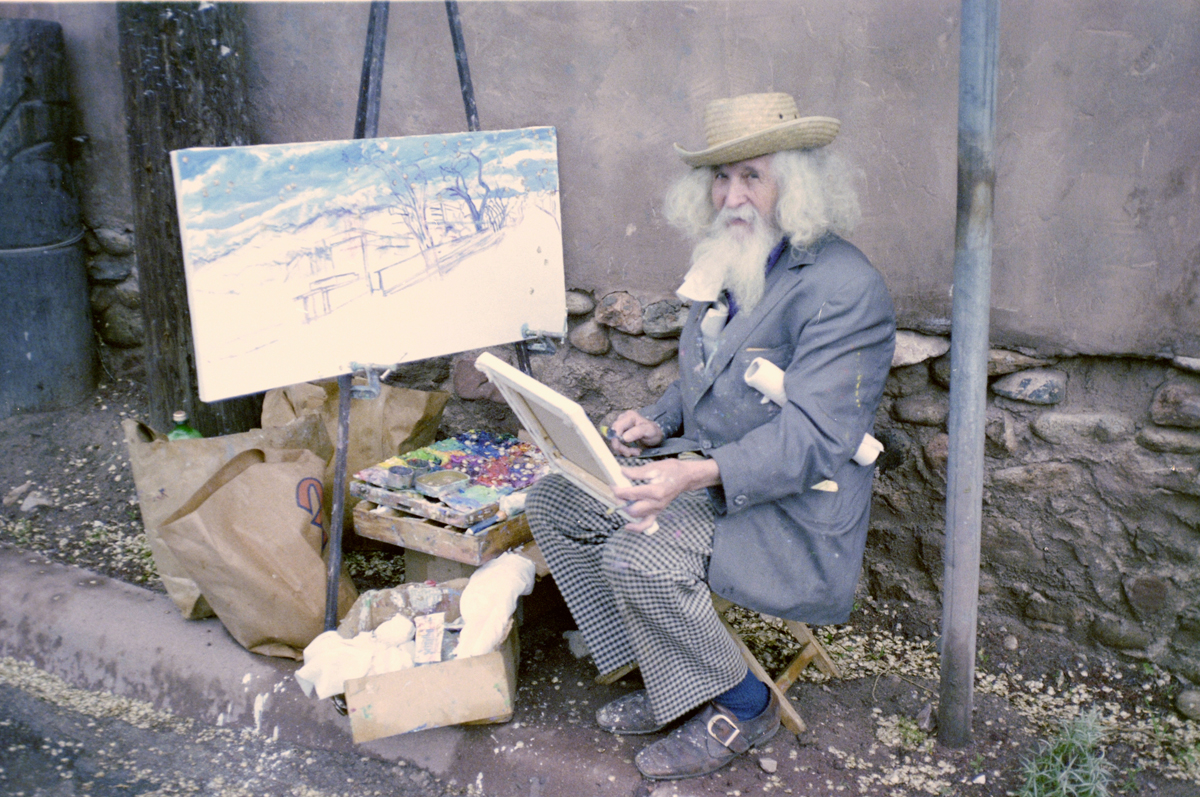

Artist Tommy Macaione is another frequent subject. His eccentric personal style, flowing white beard, and plein-air painting are captured on Magnus’s film rolls and reels from the 1960s and ’70s. Macaione, like Fényes, was special among transplants because he retained a sense of humility and knew how to live in community, unlike “those white boys who came here and named themselves the Cinco Pintores,” Maier says. Los Cinco Pintores, or the five painters, were five white, male artists who moved to Santa Fe and formed an influential collective in the early 1920s. Macaione, on the other hand, “lived in abject poverty, wasn’t predatory, and was mentally unwell, a hoarder,” Maier says. “But he was kind. He showed up. […] Multiple women have told me stories about their grandmothers who were best friends with Tommy. They’d feed his twenty dogs because he’d come to their houses and paint their gardens.”

Maier is critical of the waves of American capitalism that have cycled through Santa Fe, from the opening of the Santa Fe Trail in 1821 and the tourist-centric campaign for statehood at the turn of the last century to Ralph Lauren and Esquire magazine’s appropriative redefinition of “Santa Fe style” via glossy ad campaigns in the ’80s.

It makes me feel as if we’ve been disconnected from the original history of how Canyon Road became what it is.

“It makes me feel as if we’ve been disconnected from the original history of how Canyon Road became what it is,” he says, noting that the spiffy parts of Santa Fe often lack a friendliness, which is “a cultural dynamic you can still find anywhere else in New Mexico.”

As he develops relationships with certain art world elites such as Matteuci, Maier maintains that his creative independence has never been questioned, and that in order to continue telling new stories about Canyon Road, a certain amount of collaboration with the establishment is necessary. “There’s a lot of variation even within the stakeholder power class,” he says. Maier describes himself as a “conduit” for stories, but he’s a character on Canyon, too, by virtue of his own curiosity and the way he transmutes his enthusiasm to other kindred, chronically online spirits.

For all the “hoopla” generated by flashier decades like the free love/cheap rent ’60s and the art colony heyday of the ’20s, Maier, if he had a time machine, would travel back to Canyon Road circa 1930. “The Great Depression hit and the art colony fizzled out,” he says. “But the art scene hung on. FDR gave federal money to artists. You had Olive Rush, Gustave Baumann, [Will] Shuster, Ellis, these big names stuck it out through the ’30s, but it was still old-world New Mexico. The big changes hadn’t really started to take shape. That’s where my imagination lives.”

Collective imagination is alive in @canyonroadhistory’s posts and Reels, too, in the shared act of viewing and commenting on images and films together, saying what seeing these pieces of the past means to us, mourning what’s gone and wondering about what might have been, while hopefully also understanding that we aren’t static in history, nor is it a foregone conclusion. Canyon Road—the idea and the asphalt—belongs to everyone in Santa Fe who cares about art, as we belong to her.