Public art finds itself at the center of a number of our era’s flashpoints: the controversy over Confederate monuments; a questionably placed statue of a Fearless Girl in front of a Charging Bull on Wall Street; the role of signs and graffiti in public protest. In a world of screens and mediation, works of public art still manage to call our attention to our physical surroundings and spark curiosity.

Who is behind the “END ICE” installation on the Rail Trail? When did someone scratch out the word “savage” on the obelisk in the Plaza, and why has it been left that way? What possessed a resident to recreate Guernica on their adobe wall? Public artworks can be a vehicle for the state’s assertion of power over a place’s narrative, but they can also make space for renegade political or aesthetic interventions in shared spaces. In New Mexico, public works of art bring attention to the erasures and rewritings of history (see also: “Unpacking the Archives” on the Gilberto Guzmán mural), remembrance of legacies some would sooner forget, and playful awareness of the immediacy of the present moment.

Bruce Nauman, The Center of the Universe

1988, poured concrete, six sodium vapor lamps, iron grate, 50 x 50 x 50 ft.

Location: Albuquerque / Yale Mall, University of New Mexico

In the middle of the iron grate floor inside a cross-shaped concrete structure between Yale Mall and the UNM Duck Pond, a brass plaque designates this location as The Center of the Universe. The significance of the structure is probably lost on many pedestrians and cyclists who use the sculpture as a passage from one location to the next, but no matter. It’s either an ironic joke or a Zen koan, and how we interpret it, like any work of art, remains subjective. Nauman employed the same structure of three intersecting tunnels in at least two earlier works, both titled Room with My Soul Left Out, Room That Does Not Care. They serve, in their relatively smaller scale, as maquettes for the UNM work.

—Chelsea Weathers

Estella Loretto, Kateri Tekakwitha

2003, bronze, 90 x 36 x 36 in.

Location: Santa Fe / St. Francis Cathedral

At the Cathedral of St. Francis, the plaza includes a sculpture of the obscure Kateri Tekakwitha. A Mohawk native who died in 1680, she was canonized in 2012, the first Native saint in the Catholic Church. Her story is one of suffering, beginning with the smallpox that killed her family and left her face disfigured. Refusing to marry anyone but Christ, she practiced self-mortification and died at only twenty-four. According to some, with death her body lost its scars and became beautiful—a sign of favor from God. The artist, Estella Loretto, depicts St. Kateri’s post-mortem transmogrification, but it’s a mannered look that’s almost creepy. Clad in Pueblo clothing, the figure appears out of proportion. The joy she radiates belies her appearance, ultimately flatlining the sculpture’s success.

—Kathryn M Davis

Friends of the Orphan Signs, Donut Mart

Location: Albuquerque / Lomas Ave

In June, I moved back to the North Campus neighborhood of Albuquerque, and the routes of my daily life changed, redirecting me more and more often down Lomas Avenue. There, on the billboard of the shuttered Donut Mart, near the intersection with University Ave, was advertised: “Insomnia 99¢.” In the months that came, I noticed the mysterious signage change often, hawking new wares: “Destinies 99¢”; “Softest seas”; “Una tienda de nubes”; “Sin miedo a nadie”; “You amaze me often.” These concise poems, crafted by local nonprofit Friends of the Orphan Signs, are created with the letters left behind when the former Donut Mart closed shop: “Any size fountain 99¢ ATM EBT inside.” An exercise in poetic economy and creativity, Donut Mart (the poem, the project) continually re-awakens me to what public art can inject into what too often feels banal but is really the stuff of life—the commute, the idle minutes at a stoplight.

—Maggie Grimason

Jodie Herrera, Dolores

Location: Albuquerque / Broadway Blvd

Small in scale, extending the height of a low cement wall and only a few feet in length is Jodie Herrera’s portrait of Dolores Huerta on Broadway Avenue near the intersection of Lead, a passage to the heart of downtown. A classic Herrera design marrying portraiture and geometry, this simple ode to the labor and civil rights activist painted over desert-y browns and golds is understated; its small size makes it feel special. It’s not secret—the mural is on a busy corner—but it is exemplary of the ways both art and activism are embroidered everywhere on scales both big and small into Albuquerque’s fabric—and the ways in which these practices powerfully intersect.

—Maggie Grimason

John Cerney, Cowboy Ruckus

2016, wood, 18 ft.

Location: 73 miles north of Roswell / Highway 285

Seventy-three miles north of Roswell, you’ll intersect a showdown across the peripheries of Highway 285. Two sky-scraping wooden cowboys, painted by John Cerney in 2016, are frozen mid-standoff. One shrugs back beside the northbound lane as if inquiring “and what of it?” and the second, with knees bent, points a finger accusatorily across lanes of traffic. The cowboys depict the likeness of two brothers who own the land, and passersby become immediately implicated in their quarrel. I like these cowboys best in retrospect (they’re eighteen feet tall and painted on both sides) as I drive beyond them, watching the pair grow small through the lens of my rearview mirror until they are mere silhouettes on the horizon.

—Annika Berry

Reynaldo Rivera, Juan de Oñate

1991, bronze

Location: Alcalde, New Mexico, and SITE Santa Fe, foot recast anonymously in 2018

Five hundred years after the fact, karma announced itself in Alcalde, New Mexico (north of Española). The foot of a statue honoring Juan de Oñate was infamously removed one night in the late nineties, as retribution (and metaphor) for the conquistador’s sixteenth-century violence against the Acoma Pueblo and his cruel punishment of amputating the right feet of Pueblo men after the Spaniards’ takeover. While the statue’s appendage has since been re-cast and patched, no one is much interested in forgetting the charged message of its careful removal. Today, the gesture is immortalized in a ceramic-cast replica at the 2018 SITE biennial, where it sits—a carefully curated ghost—in a well-lit niche.

—Annika Berry

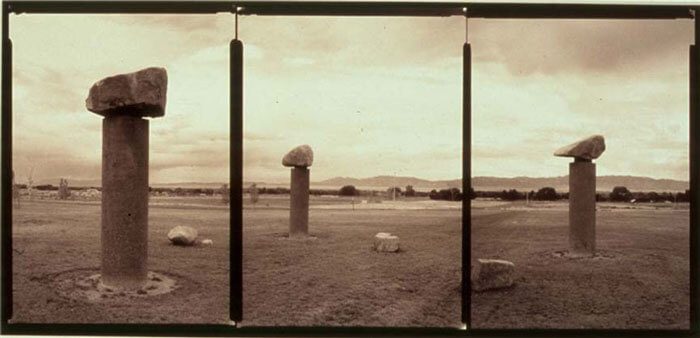

Paula Castillo, Aquila

2001, concrete and granite, 100 x 100 x 16 ft.

Location: Belen, New Mexico

Belen High School, home of the Eagles, sits near I-25 on the outskirts of town. Nearby Eagle Park can be crowded on a Saturday. A group of children play hide-and-seek; a boy crouches behind one of many boulders in a field of thick grass. The boulder, as it happens, is also a star—one in a representation of the Aquila constellation, created by Paula Castillo for the park in 2001. Aquila is Latin for eagle, and the bird appears in various Greco-Roman mythologies. In the sky, its wings trace three main stars, which Castillo represents with three massive granite rocks fixed atop cylindrical concrete pillars. The arrangement of stones across the park, of various sizes and heights, mimics the distance of the constellation’s stars from Earth and grounds mythology in the playful everyday.

—Chelsea Weathers

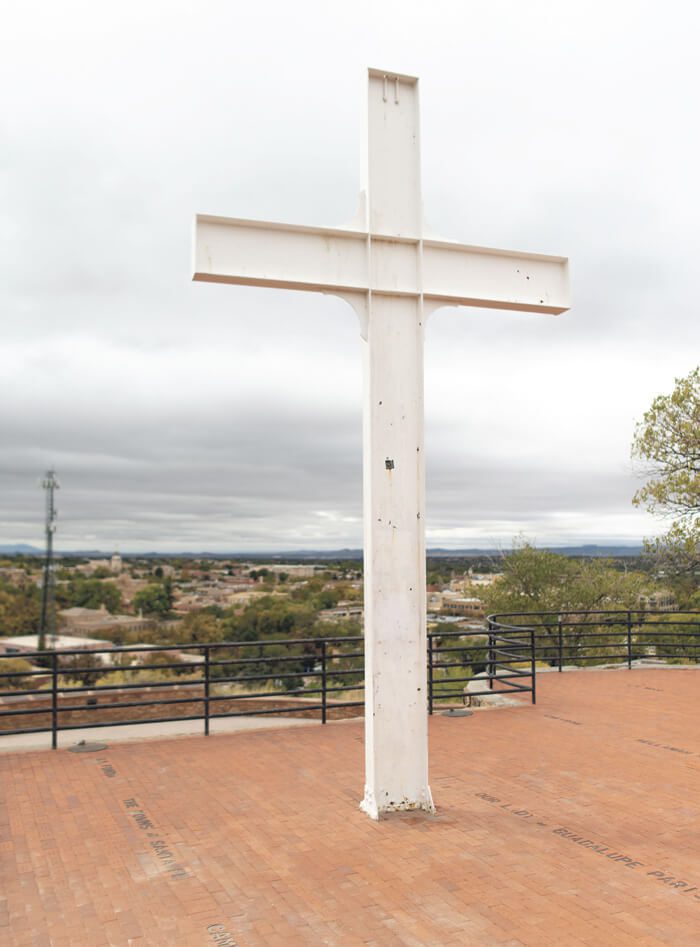

Ralph E. Twitchell, Edgar L. Street, and Walter G. Turley, Cross of the Martyrs

1977, steel.

Location: Santa Fe / Fort Marcy Park, 616 Paseo de Loma

If you hike up the switchback staircase to Cross of the Martyrs, a monument on a hilltop just northeast of downtown Santa Fe, you’ll pass a series of placards espousing a decidedly colonialist history of our city. I usually approach from Kearney Avenue and through the Fort Marcy Park entrance, so that I can stroll down the staircase and unwind Santa Fe’s bloody history one invasion at a time. The Indigenous communities of New Mexico had a similar idea in 1680, when they initiated Popé’s Rebellion (or the Pueblo Revolt) and drove Spanish colonists from their ancestral lands. There were numerous casualties on both sides of the conflict, including the twenty-one Franciscan priests listed on this 25-foot-tall steel cross. The sculpture is a peculiar relic in a city that’s obsessed with commemorating colonial “victories.” Here, history is told by the losers, and no number of bronze placards can erase the twelve remarkable years when Santa Fe’s still-unceded Tewa land was free.

—Jordan Eddy

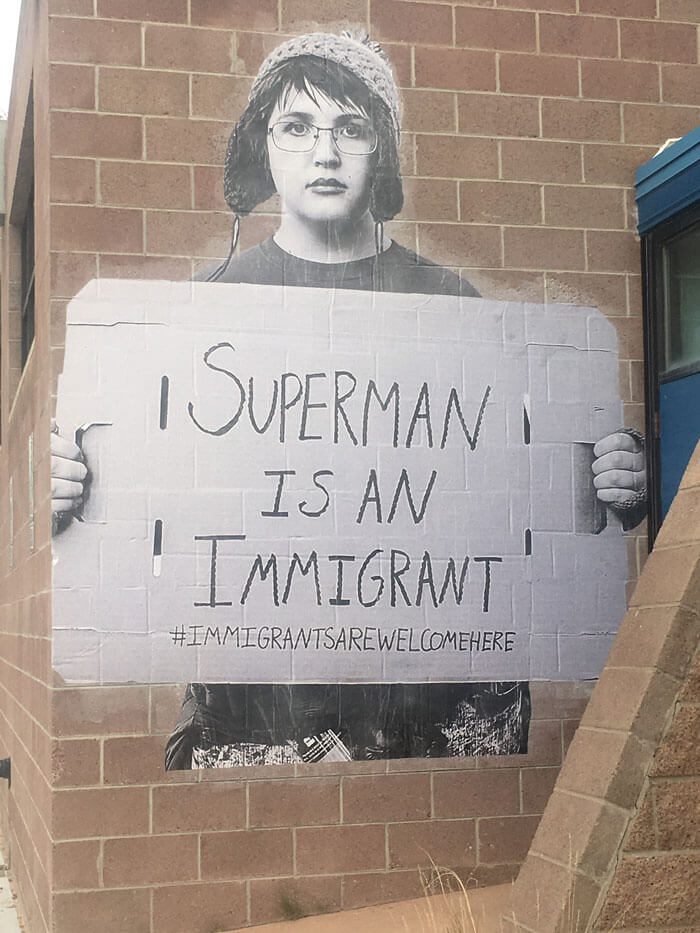

Santa Fe Dreamers Project Murals

Location: Santa Fe / La Farge Library, Railyard Park, United Way

On the side of La Farge Library, a woman holds a sign that reads “Superman is an immigrant.” She is a story tall and she isn’t smiling. This mural is part of an ongoing series of public works from the Santa Fe Dreamers Project featuring photos of Santa Fe residents who are immigrants themselves or immigrant supporters, taken by six local photographers. Some of the murals incorporate signs in both Spanish and English, and members of the community collaborate with their installation and removal. The murals call public attention to the ongoing attacks on immigrants and their rights under the current administration. They also make a direct connection between the viewer and the larger mission of the Santa Fe Dreamers Project: to provide free legal services for immigrants in New Mexico. Find out more about their important work at santafedreamersproject.org.

—Jenn Shapland

Santa Fe Interfaith Council and Labyrinth Resource Group, Frenchy’s Field Labyrinth

1998, clay and straw

Location: Santa Fe / 2001 Agua Fria St

Six weeks ago, Frenchy’s Field was circled in Cowpen daisies and its labyrinth was half-hidden under a blanket of gold. Created in 1998 and maintained by the LRG (Labyrinth Resource Group—a Santa Fe nonprofit committed to the “power of the labyrinth”), the Frenchy’s Field Labyrinth has seven circuits that rise upward so that, as you follow the pathway, you descend into a hidden interior. The last time I visited, I discovered a friendship bracelet, a coiled leather belt, and a journal filled with unrequited love notes safely tucked within its walls. “The labyrinth is like the path of life,” the LRG states on its website. It is, in the case of Frenchy’s Field, certainly a peek into the lives of others.

—Annika Berry

Stone Monument to Japanese Internment

Location: Santa Fe / Frank S. Ortiz Dog Park

2002

A stone perched on the edge of the dog park in the Casa Solana neighborhood, behind the Coop, is the only public indication of what was once an internment camp for a total of nearly 4,500 Japanese people in Santa Fe. During WWII, New Mexico had four Japanese internment camps, and the US incarcerated over 120,000 Japanese people. The Santa Fe camp also held some German and Italian immigrants during the war. While held at the camp, many people lost their homes and other belongings, unable to maintain their bank accounts or pay their mortgages. The Santa Fe camp remained in use until April 1946, though many locals were unaware of its existence or what went on there (some, though, tried to storm the camp during the war to harm the prisoners). The ongoing internment of immigrants along the US-Mexico border in detention facilities, the separation of families: in the context of the monument, these events feel all too familiar.

—Jenn Shapland

Mac Vaughan, Thomas Silvestri Macaione, “el Diferente”

Location: Santa Fe / Thomas Macaione Park

1995

In a place that’s jam-packed with artists—and artists’ ghosts—it takes a particularly colorful character to score a memorial that’s referred to as “The Artist.” The not-quite-life-size bronze sculpture depicts Thomas Silvestri Macaione, and it stands at the center of a downtown park that bears his name (but is casually known as Triangle Park). Tommy was an American artist of Sicilian descent, born in Boston in 1907. He arrived here in 1958 with plans to continue on to California, but we all know how that goes. As indicated by the gooey palette balanced on a crate at his feet and the textured canvas on his easel, Tommy painted in an impasto style inspired by the Impressionists. Among his many nicknames was “the Van Gogh of Santa Fe.” A button on his jacket reads “World Peace,” a reference to the signature issue of his many political campaigns—for mayor, governor, president, etc. The puppy at his feet represents his passion for adopting pets (which got him in trouble with the city later in his life), and his wild hair is its own long-running joke: Tommy was also a professional barber. He died in 1992, but his legend lives on through this sculpture and “Tommy Macaione Day,” which is on November 13.

—Jordan Eddy

Georgina Farias, Virgen de Guadalupe

Location: Santa Fe / Santuario de Guadalupe, 100 S Guadalupe St.

2008

Outside the Santuario de Guadalupe, the oldest shrine in the USA to the Mother of the Americas, stands a cast bronze of La Virgen. Beloved by many, Catholic or not, this Mary is one of the people. The sculpture’s monumental size makes it all the more effective. Unfortunately, the face we gaze upward into lacks the sweet tranquility of the original Guadalupe from 1531. Still, everything else about the figure—from the blue mantle of stars on her back, to each separate glimmer of light that radiates from her form, to the eagle-winged angel who holds her aloft—is spot on. This is a public installation that serves its purpose well, whether the viewer is deeply devout or merely a curious onlooker.

—Kathryn M Davis