Santa Fe Style

I tucked myself between the open front door and an elegant, old wood easel next to the Acequia Madre House’s immense living room’s antique grand piano, taking a moment in my hiding place to observe the extraordinary space, rarely open to the public. I took in the deeply stained beams in the grand sala (an extra-large, often quite tall living room, a traditional architectural component of wealthy Spanish homes), the large arched opening into the dining room with its traditional kiva fireplace, the collection of antiques from all over the Spanish empire, and the gorgeous, massive European-style fireplace with Talavera tiles so delicate that they seemed really old and possibly Portuguese. The front door was open to allow more light into the space while I took 360-degree photos, so I could revisit the space when I needed more detailed information for the Historic Cultural Inventory Form I was preparing. I looked out through the open door towards the mountains over the rare jewel of a lawn and enjoyed the view from the Spanish Pueblo Revival porch. Something prickled at me. This building had been described in books and in previous documentations as Territorial style. But, while it has elements of Territorial style (brick copings, pedimented wood trim, and shutters), it also has details from Spanish Pueblo Revival, including an inset porch with carved wood posts, corbels, beams, and vigas, and windows and doors set in the rounded inset openings architects call “bullnosed.” Those details didn’t fit Territorial style—plus the flow from room to room on the front half of the house’s plan echoed Santa Fe’s Indigenous and Hispanic architectures, while the back half of the house’s central hall, mudrooms, and two unusual sitting rooms with Colonial Revival fireplaces seemed to embrace earlier American styles.

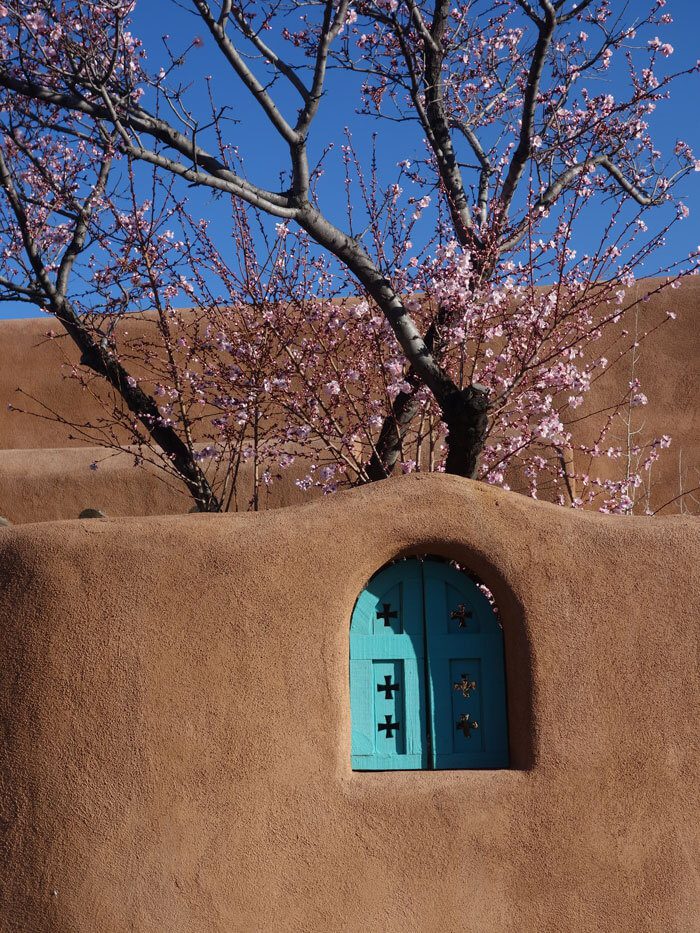

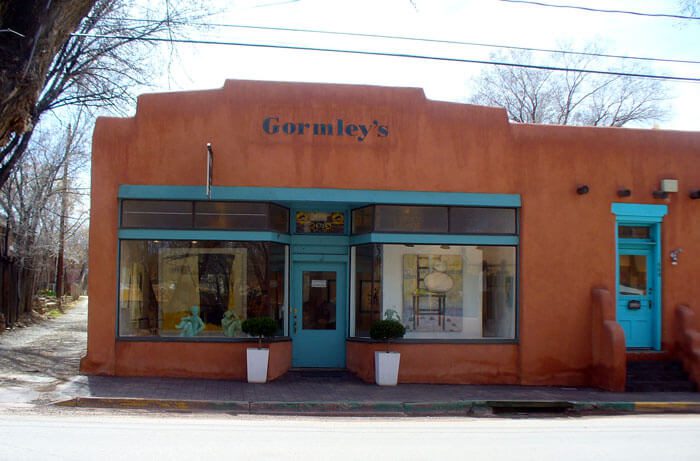

For me, this combination of elements placed the house squarely in the signature Santa Fe Style: an architectural assemblage of parts borrowed from precedent styles and codified by the City’s Historic Preservation Zoning Ordinance in 1957 as the only architectural style allowable in Santa Fe, which still applies today. A Santa Fe Style building might take on aspects of Puebloan terraced puddled adobe blocks or the simple lines and elegant wooden and adobe block structures of Hispanic vernacular homes. It will often have Territorial details like the Greek-style pediments over windows and doors, delicate wooden porch details, and brick copings on the porches of El Zaguán and many other homes along Canyon Road. It might even feature a Victorian detail or two. Or it might have details of California Mission style, like the Guadalupe Church or the old Santa Fe Depot. Really, Santa Fe Style is based on simple precedent forms put together in inventive ways, a compilation designed to give that “Santa Fe feeling.”

Spanish Pueblo Revival Style

My curiosity demanded I explore every nook, turn, and stairwell to discover what magic was next.

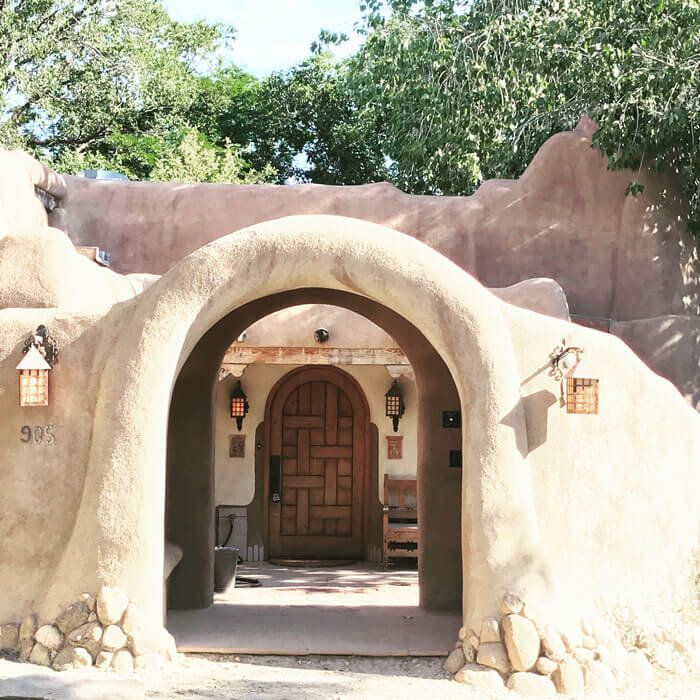

Some years ago, before I moved to New Mexico, I was walking around La Fonda on the Plaza, and there were so many layers of openings and wall surfaces—an effect that architects call “massing”—that I could not figure out how to get inside. I walked right past two entrances, thinking they were storefronts, until I looked up and discovered the places where the doors have taller massing from raised and stepped parapets. Once inside, everywhere I turned were layers: layers of spaces, layers of surfaces, layers of colors, and so many rich textures and finishes the space felt incredibly decadent. My curiosity demanded I explore every nook, turn, and stairwell to discover what magic was next. I was completely taken in by the hand-forged iron railings and lighting, tinwork sconces and chandeliers, and spectacular hand-carved wooden details—romantic vestiges of the way the Arts and Crafts movement influenced (and some might say reinvented) New Mexican traditional crafts. This was my first real introduction to Spanish Pueblo Revival style, conceived in the early-mid twentieth century, about the same time as Santa Fe Style, and implemented by wealthy white transplants who hired architects to accomplish something “better” than the extraordinary multicultural architecture vocabulary that was already in place with “Old” Santa Fe Style.

Reflecting Backward, Moving Ahead

As I was preparing to give a talk a couple of weeks back celebrating my ten years of preservation work in New Mexico, I reflected on these formative moments and how they shifted my paradigm of design. I thought back on the five hundred or so homes I had surveyed in Santa Fe, Acoma, Taos, and Taos’s outlier villages and how many times I had been wrong in my assessments of those places, because I was looking purely at the architecture and not really attempting to understand the culture(s) that made them. I forgot about the “why.” The “why” of Santa Fe Style was to formalize what people loved about the culturally rich architectural fabric after many of our local styles were usurped in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century in order to entice tourism and white settlement, which would encourage the U.S. to make New Mexico a state and recognize Santa Fe as its capital. And the “why” of Spanish Pueblo Revival was to take all the design techniques that make New Mexico architecture great, to streamline them, and to re-form them into something new. Spanish Pueblo Revival architects sought to make the style elite in every way by adding layers of meaning and expense, while also being “philanthropic” to the local builders and craftsmen by giving them good work within revived craft traditions that echoed those of their ancestors—but at a more opulent level than the originals. The luck in these early examples of creative placemaking was that these well-intentioned, wealthy (and often female) advocates might have just saved some important cultural traditions by resurrecting disappearing traditions of pottery, building, and craft along the way. (Whew. Score one for good intentions!)

My point of view on these styles also changed when I developed a disability. As it happens, I am going blind from macular degeneration, and currently I also have a busted hip. These two impediments prevent me from driving at night and generally slow me down. However, they have also lit up my other senses. My hearing is more attuned. My sense of temperature has changed, so I am aware of minor fluctuations like the draft from an unlocked window or the warmth of sunlight streaming into a space. I want to touch things to experience their texture and their coolness or heat now. I even enjoy tasting my architectural subjects from time to time, a trick I learned from Pueblo friends that reveals hidden building materials.

This sense of being more fully present brought about by my disabilities has changed the way I “see” buildings. I notice the difference between the efficient and orderly Territorial-style buildings, which seem to say, “Come in, here’s where to go, thank you, and have a nice day,” and the exploration-inducing “Come in and stay awhile” layering of Spanish Pueblo Revival. I physically experience how the Hispanic period buildings grew one room and one door opening at a time as families expanded. The hallway was relatively unknown until the Americans decided to make sure they did not have to go through everyone’s bedroom to go “make water,” as my grandma says.

I’m learning to hear the difference in the way earth plaster and stucco tink when thunked.

There’s a difference to the way each of these spaces feels as you move through them because of the way they unfold onto each other. I feel the coolness, smell the earthen walls and floors, and feel pops of light and rushes of air from the tiny windows and doors of the earliest Indigenous and then Hispanic architecture. I bask in warm sunlight through the large windows that the railroad made possible, bringing larger spans of glass and lengths of wood from early wood mills. I can even walk by a sunny window and feel what direction I am facing. I can hear someone’s heels clacking on the floor and tell you what kind of surface they are walking on. I’m learning to hear the difference in the way earth plaster and stucco tink when thunked. I’m learning to really be in the space. My heightened senses and lots of practice make this happen almost instantly for me. But these kinds of awareness are available to anyone who wants to practice this, just by becoming very still and really present.

Architecture has become an experience that I have, rather than an object to behold. Exploring buildings this way teaches me that there is so much more to our architecture than we typically take time to see.

In order to apply for a permit to do work on a historic building in Santa Fe, the applicant must establish the building’s style and associated time period. Assessing the style has been made more difficult because the State of New Mexico treats Santa Fe style differently than the City of Santa Fe. In the State Historic Preservation Division’s 2013 draft classifications, probably the best current guideline for identifying historic building styles in New Mexico, Santa Fe Style is never mentioned. The invisibility of Santa Fe Style in the state guidelines complicates preservation, renovation, and even new construction, as it is in direct contradiction with the city ordinance of 1957, shepherded by John Gaw Meem, that requires buildings in the historic districts to adhere to Santa Fe Style. What’s confounding about this is that if Santa Fe Style were a building, an age of 61 years and the association with a major New Mexican architect (let alone several) would qualify it for the National Register of Historic Places, which the state administers. If a building in the style is eligible for recognition at a national level, and if the city mandates the style be followed, how can the style not be acknowledged by the state?

Historians have sometimes had to utilize Spanish Pueblo Revival to describe Santa Fe Style because that is the closest option available within the state’s recognized styles. Then, some half a century ago, someone put a slash between the two styles so that Santa Fe Style/Spanish Pueblo Revival style was acceptable, as if the two styles are simply different interpretations of the same architectural language. But beyond what I can see, my senses have taught me that these are not the same, or even interchangeable. If Santa Fe Style were a bowl, every precedent style—Puebloan, Hispanic Vernacular, Territorial, Northern New Mexico, Mission, Bungalow, Spanish Pueblo Revival, etc.—would be a different fruit in that bowl. Most of those fruits are those sweet little apples and pears and apricots that grow so well here: they are smaller and have a simpler taste profile, but they are perfectly adjusted to the climate and are deeply connected to this place, flourishing even in heat and drought. Spanish Pueblo Revival just happens to be the most magnificent, most expensive, most flamboyant fruit in that bowl—Strawberries Arnaud of Santa Fe, if you will. But, like the other styles that might be combined to make a building Santa Fe Style, it is not only Santa Fe’s—it belongs to everyone (with enough money) in New Mexico.

In order for Santa Fe to find a sustainable path through the next hundred years, I hope our leaders make the effort to reconcile the limitations Santa Fe’s Land Use Department has imposed on work in the historic district and those that have been imposed by the State. I, for one, would like us to really think about what we really are and where we want to go. I would like the City, and our leaders, architects, and preservationists, to appeal for the formal recognition of Santa Fe style, because this unique architecture really starts to encapsulate more of the complete history of Santa Fe—with all of our architectures, our arts, our stories, and our peoples represented.