Ben Coleman, a Denver-based sound and performance artist, explores the aesthetic and conceptual contours of noise, music, and the body through installations and live events.

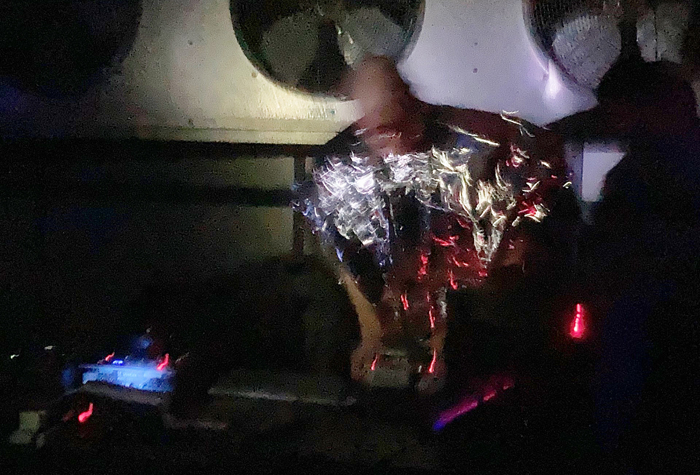

Standing behind a folding table in a dark recess of the soon-to-be-demolished iMAC building in Denver’s RiNo District, artist Ben Coleman strips off his shirt, then dons a headlamp and Mylar cape. For the next several minutes, he leans into various effects pedals scattered atop the table, pounding them with his fists and producing a relentless wall of abrasive noise.

Moments later, Coleman grabs a small, plastic megaphone retrofitted with a pick-up and screams into the apparatus. His voice, amplified by the megaphone and distorted by whatever sonic gadget he has affixed to it, emanates throughout the space in an electro-animalistic howl.

As he screams through the device, the artist walks around the table and into the audience. He drops to his knees and pounds a fist against the concrete flooring, wailing the entire time. The Mylar cape rises and falls in unison with Coleman’s movements, reflecting the dim ambient lighting with pink, blue, and white flashes.

And, just like that, the performance ends.

While it may have resembled an exorcism swaddled in a sonic assault, Coleman conceptualizes this performance as something much different. Sitting in his Denver area studio a week later, the artist mentions that “it’s about joy and catharsis. Yes, [last week’s performance] was sonically aggressive, but, for me, it’s rooted in things like dance music and techno. It’s about physical joy, whether it’s in repetition or extremity. So, for me, it was a gleeful performance, I was having so much fun. I didn’t feel like there was any anger I wanted to get out—just energy.”

By reframing an outwardly aggressive performance as an inward expression of joy, glee, and a cathartic energy release, Coleman undercuts his external presentation with a gentle, conceptual understanding of his work. Such contradiction opens up a space where presentation belies purpose, allowing an audience to reimagine or reassess our cultural assumptions about the meaning of a sound or appearance.

The United Kingdom-born Coleman began his creative career in theater and performance; although he soon shifted his focus to music, moved to London, and began playing the club circuit. However, he notes that the city was “really hard for musicians. It was impossible to move gear, own gear, have a drum kit, or find a drummer. And it was just so expensive.”

Feeling these material and financial pressures endemic to London, Coleman relocated to the States in 2003 where he immersed himself in Atlanta’s experimental and improvisational music scenes and founded a band. “I could do circuit bending gigs and stuff like that,” he says, because “there were all these great fucking musicians everywhere… who wanted to do weird things.”

While he thoroughly enjoyed the Atlanta music world, all good things come to an end. The co-founder of Coleman’s band moved to Chicago to work for Wilco as a keyboard tech, sending Coleman’s group into an extended hiatus.

Instead of forming a new outfit, Coleman decided to lean into his theater and performance art past.

“I used the trappings of live music to make the performance happen. I would still have a live band—the difference being that I would dress like a seagull and put myself in the hospital or whatever it might be,” explains Coleman about a performance in which he had to seek medical care after smashing himself with a mirror. “Just upping the ante on that side of things. I was really into a lot of esoteric shit, such as spell casting. It gave me an excuse to do all the weird things that I wanted to do, like ritual performance.”

In 2019, Coleman relocated once again—this time to Denver, where he was awarded a RedLine Contemporary Art Center residency. The geographic move coincided with an aesthetic and conceptual shift to sound installations that read more as sculptural art than performance art.

For instance, his artwork titled Drown, which first appeared at the now defunct Friend of a Friend gallery in Evans School, consisted of five mop buckets filled with water. Each bucket held a mop protruding upward with a small speaker affixed to the top of their handles. The speakers amplified the recordings of “about twenty-five folks saying the word ‘shush’—and the idea was that it was human-made white noise. A shifting cloud of white noise. You would never hear the same two shushes together circulating around this space.”

While the sounds of Drown were integral to its execution as an installation work, so were the objects he chose to employ and his desire “to do something visually appealing. The fact that [the gallery] was in an old school gave me memories of janitorial supplies. The smell of bleach and cheap disinfectant reminded me of comprehensive school in the UK in the ‘80s and produced a strong sense memory.” Likewise, Coleman adds, that he likes “to do surreal shit just for the sake of it because it gives me kicks.”

More recently, Coleman participated in the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver’s Breakthroughs, a fifteen-year retrospective group show featuring various RedLine artists. For the exhibition, the artist contributed Eavesdroppings (Exchange), which was situated along a hallway corner. On the one side of the corner, a bank of twenty-five tin cans stacked upon their sides rested upon a white pedestal. Strings affixed to their bottoms met at a singular point along the rear wall. On the other side of the wall, strings emanated from a singular point and radiated out and upward toward the ceiling. Tin cans on the end of each string hung from the ceiling with thin fishing wire, so it appeared as though they were magically levitating or frozen in flight. Synthesized voices from virtual assistant technology emanated from a hidden sound source. The articulated phrases were mundane snippets of language that programmers use to train AI voice algorithms.

Eavesdroppings (Exchange), according to the artist, is about “introducing an absurd solution to [counteract] being surveyed. Don’t use a cellphone or smartphone, use a tin can on a string instead. I was reading a lot of pataphysics at the time [and embraced] the idea of imaginary solutions to problems. [In this way], it’s an effective way of communicating and [avoiding] the general fetishization of tech in the art world.”

And what does the future hold for an artist whose practice varies so widely from performance to installation to theater to composition?

“I’m working with various obsolete media,” Coleman says. “I own a wire recorder that I hope to rehabilitate because the material you record on is so beautiful. Wire recorders predate tape, but it’s the same principle. You use very thin, stainless steel wire on two reels that passes through a magnet and leaves the sound magnetized on the wire. I’m interested in the materiality of the stainless-steel wire and would like to do some installation work with that—the idea of sound crystalized in space.”

“I have all kinds of weird ideas. For example, I want to compose a drama for cassette: a dialogue-driven play that is activated by the play and pause buttons on the decks.”

Whether his future work explores wire recorders, cassette recorders, or something else entirely, one can only assume that Coleman’s output will be quirky, absurdist, conceptual, and, of course, sound-based.