Duwawisioma’s (Victor Masayesva Jr.) retrospective exhibition Màatakuyma at Andrew Smith Gallery in Tucson solidifies the Hopi artist’s importance in contemporary photographic and Indigenous artistic discourse.

Duwawisioma (Victor Masayesva Jr.): Màatakuyma

November 30, 2023–March 23, 2024

Andrew Smith Gallery, Tucson

Màatakuyma, or “Now it is becoming clearer to me,” at Andrew Smith Gallery is a solo exhibition of work by Duwawisioma that compellingly demonstrates the scope and significance of his practice. After showing the Hopi artist’s work consistently for over thirty years, Smith now presents a retrospective, highlighting the artist’s lengthy career and influential role in contemporary photography. Despite only recent large-scale institutional interest, Duwawisioma is arguably one of the most prescient contemporary artists of the American West for his clever use of collage and color to integrate sociocultural themes.

Born in 1951 in Hotevilla, Arizona, Duwawisioma (Victor Masayesva Jr.) is primarily known as a lens-based artist, but also works in sculpture, printmaking, and video. He studied literature and photography with Emmet Gowin at Princeton University, but returned to the Hopi lands where he lives and works from today.

Duwawisioma’s photographic work is uniquely both painterly and sculptural. His colorful, layered compositions portray ancient Hopi traditions through contemporary visual language. Ultimately, he reveals how Indigenous experience has simultaneously evolved counter to—and alongside—those traditions through forced assimilation, technological development, and climate change.

Màatakuyma is on view in primarily two rooms, with a few images in the third room among other works in the gallery’s collection. The first room features early work and Tuuviki (Mask), an ongoing project in which the artist crafts digital katsinam. Inspired by traditional migration patterns, Tuuviki is the Hopi practice of imagining spirit personalities associated with specific places or natural occurrences. The second room is dominated by Natwani, a set of twelve prints that narratively examine the Hopi lunar and agricultural calendar. Each image represents a cycle stage and its corresponding event, be it planting, moisture, dancing, or the pervasive sound of the wind. Natwani is displayed alongside two sculptures, an artist book, and a video.

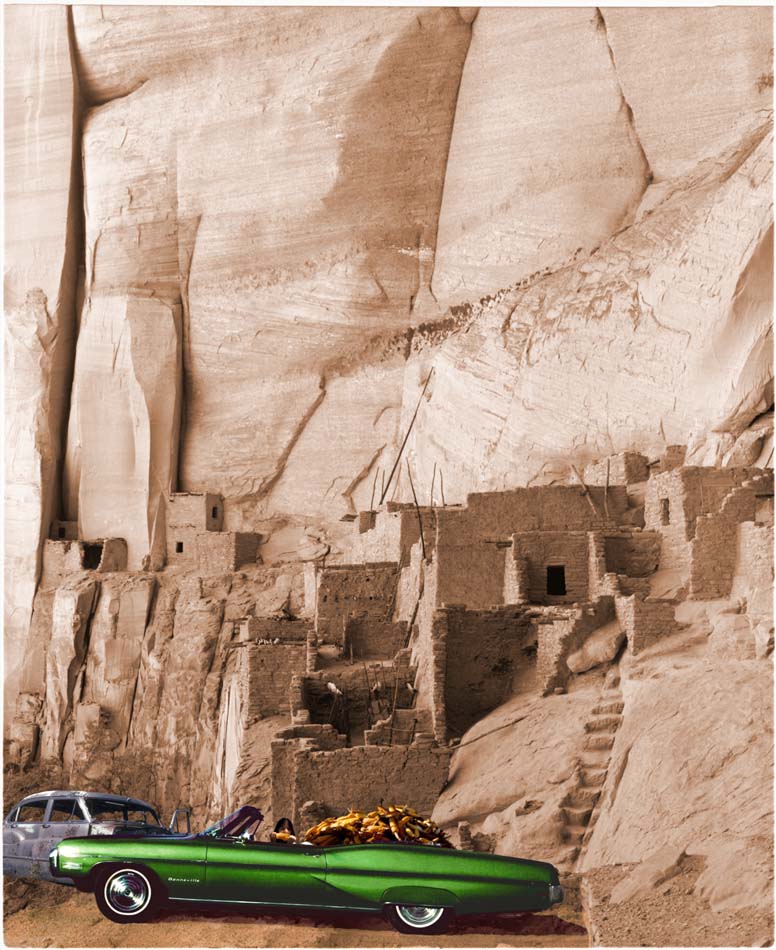

In Tupepta (from Natwani) (1997), a girl eats from a pile of corn inside a metallic green Pontiac Bonneville parked at the Kawestima ruins. At first glance an offbeat juxtaposition of pigment and texture, Tupepta asserts the preservation of agricultural customs across Hopi generations. While ruins tend to symbolize death and abandonment, Tupepta stages a living history despite the sociocultural differences between today and when the ruins were occupied; the modern car sits still at the ruins and carries the tribe’s primary food source.

Nanavöga (from Tuuviki) (1996) illustrates a katsina resting on a bed of cash and dried pine needles, looking forebodingly across a bridge towards the viewer; one of its eyes is a casino slot machine and the other a film reel.

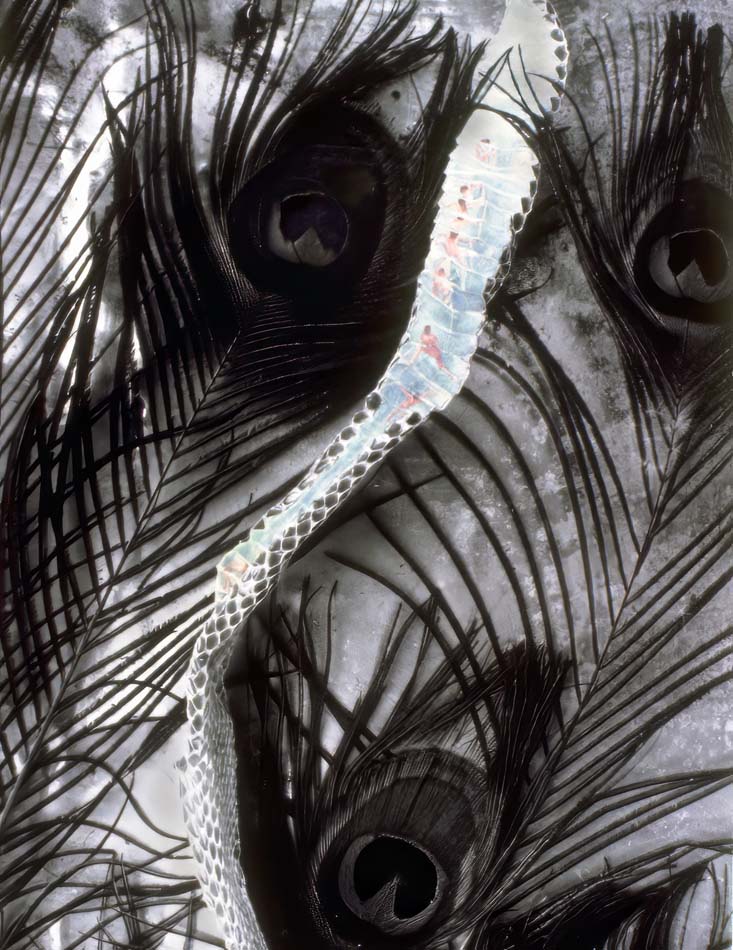

Öngtupga (The Grand Canyon) (from Tuuviki) (1990/2023) depicts a colorful snakeskin lying curved among peacock feathers, as if slithering through them. Painted men climb up the snake’s scales, journeying along its underbody on, in the artist’s words, “an ancient pilgrimage to a salt deposit in what is now known as the Grand Canyon.” The feathers’ eye-like design intimates a katsina watching the men on their difficult trek. At the same time, the faded paint colors point to an evaporating tradition of pilgrimage, and the singular peacock feathers—typically iridescent and sold in stores for costume and decoration—could imply nature falling apart.

Overall, Màatakuyma is a strong, broad presentation of Duwawisioma’s work. Joining elements of Hopi spiritual culture, agricultural practice, and relevant history, the artist inductively paints a portrait of Hopi experience over his lifetime, expressing the ways in which the local can represent the universal. While the gallery offers enough wall text for in-person visits, the exhibition webpage offers a deeper examination into Duwawisioma’s life through direct account. Especially for those new to the artist, the gallery could have better described his importance within photography in the physical show. As the art world has turned its gaze towards Indigenous artists in recent years, witnessing Duwawisioma’s significant career and practice provides opportunity for a more thorough study of contemporary photography.