Archival research can often feel like one percent intuition and ninety-nine percent dumb luck. That was certainly how it seemed last September when I chanced across a receipt buried among the voluminous correspondence of American artist Georgia O’Keeffe, stacks of which are housed at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library in New Haven. This receipt from Santa Fe Upholstery Co. listed the costs of hardware and labor for the installation of a new window. After two frustrating weeks of research at the Beinecke and several months of fruitless searching in the archives of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, this handwritten receipt finally answered the question that had stumped me for so long: when exactly had New Mexico’s foremost modern painter knocked out the wall of her sitting room and replaced it with a massive picture window? Hidden in an archival folder titled “General Correspondence, S” that I had pulled on a whim and out of sheer desperation, here at last was the key date: October 22, 1964.

My inquiry into the elusive origins of this window came at the behest of the team currently creating a conservation management plan for O’Keeffe’s National Historic Register–listed home in Abiquiu, New Mexico. When I met with the conservation team in April 2019, they were in the process of evaluating the structure’s material condition. Over the course of a warm spring day, I watched the team—comprised of historic architects, adobe conservators, historic site managers, and structural, environmental, and geo engineers—examine many areas of concern in, around, and on top of the adobe house, using radar, infrared imaging, and digital resistance probes. As an academic architectural historian, I spend more time looking at floor plans in archives than actually touching buildings, much less climbing on their roofs. This was a whole new world. My role in this project was to provide additional historical context about the house’s architecture and how O’Keeffe made it her own—details that might help inform the team’s recommendations. Based on their findings, the team narrowed in on a few areas of focus that they wanted me to address, including the wall-spanning window in the sitting room.

Far from being merely panes of glass in a simple, custom-made wooden frame, this inscrutable window is a portal into a particularly productive and undervalued part of the artist’s career.

On purely visual grounds, this three-paned picture window flanked by two screened vent doors is a stunning architectural intervention. From the inside, looking out, the window with its white curtains frames a feathery tamarisk tree: lush and verdant in summer, stripped and austere in winter. From the outside, looking in, some 16,400 visitors in 2019 peered through to catch a glimpse of O’Keeffe’s immaculately furnished sitting room. But the conservation team became particularly interested in and concerned about this window when they realized that it is not structurally connected to the rest of the room. That is to say, the sitting room’s vigas—the large wooden beams that tie opposing walls together and support the roof in traditional New Mexican architecture—run parallel to the window. This means that the wall containing the window is floating on its foundation, with only the mass of the stacked adobe bricks of the surrounding walls “pinching” it in place. In order to make important decisions about the material conservation of the window, we needed to know more about exactly when O’Keeffe installed it and why.

After years of stalled negotiations, O’Keeffe succeeded in purchasing the site at Abiquiu from the Catholic Church in 1945. Maria Chabot, O’Keeffe’s resourceful but mercurial friend (and sometime Ghost Ranch housemate), oversaw the initial reconstruction of the house with the help of local builders. For the most part, Chabot’s design followed the existing floor plan of the nineteenth-century Spanish hacienda, occasionally knocking out a wall or opening up a new doorway—as in the sitting room, where the demolition of a wall between two smaller bedrooms created one long living space. Chabot’s design became the template that O’Keeffe would revise, update, and remodel during her long occupancy in the house, from 1949 until she relocated to Santa Fe in 1984 (two years before her death at age 98).

What was going on in the artist’s life and career that prompted her to undertake this particular renovation in late 1964?

As was the case with her enigmatic black patio door, O’Keeffe frequently painted the same subject over and over again in series to work out compositional ideas. She brought that same strategy to her houses, restlessly reinventing many of their key rooms. Over the course of her thirty-five years at Abiquiu, O’Keeffe added and moved fireplaces, replaced flooring, and changed wall colors. But the sitting room was the locus of O’Keeffe’s tendency towards domestic reinvention. Around the same time that the picture window was installed, she had two adobe hassocks added to this space, only to have them removed again and replaced with movable, upholstered versions some ten years later. Sometime in the late 1960s or early ’70s, O’Keeffe also had the sitting-room fireplace moved so that she could enjoy a fire’s warmth while sitting on the adobe banco near the new window. Furniture, rugs, and art were rotated frequently, and the walls went from lustrous white to adobe brown in the early 1970s.

Piecing together a rough timeline of these changes proved a considerable challenge—a process that left my office looking a little like the den of a conspiracy theorist with its litter of floor plans and vintage photographs. My discovery of the dated receipt at the Beinecke Library was a relief but raised a whole new host of questions: What was going on in the artist’s life and career that prompted her to undertake this particular renovation in late 1964? Was O’Keeffe inspired by a particular architectural precedent or aesthetic concept?

The window has long invited multiple interpretations, based on the viewer’s own background and history. On the first tour I took of the house in 2017, one of the visitors in my group remarked that the window seemed “very Frank Lloyd Wright.” Giustina Renzoni, the historic properties manager at Abiquiu, has a background in Spanish colonial art and sees a biombo screen. I’ve also heard docents compare it to a painted trifold Japanese screen or a Japanese woodblock print. I personally could not get over how similar O’Keeffe’s window appears to the one in the living room of the Bauhaus-inflected Walter Gropius House (built 1938) in Lincoln, Massachusetts. Part of the window’s appeal is that it supports all these different readings, mirroring our own expectations back to us. But my research showed that the window can tell us a lot about the creative life of O’Keeffe. Far from being merely panes of glass in a simple, custom-made wooden frame, this inscrutable window is a portal into a particularly productive and undervalued part of the artist’s career.

REVELATION 1: AS O’KEEFFE’S CANVASES GOT BIGGER, SO DID HER WINDOWS.

O’Keeffe frequently talked about “thinking on a wall” and the necessity of blank, neutral wall space for her process of visualizing a composition. (1)

1 Chris Eyre, director, Memories of Miss O’Keeffe (2017). In fact, Maria Chabot’s original design for the reconstruction of the Abiquiu house accounted for this tendency by purposefully including large stretches of uninterrupted wall space where the artist could envision her paintings or actually hang them to test the reactions of visitors.

Around 1960, O’Keeffe started producing paintings in a much larger format. Many of her larger canvases from this period draw on the views that the artist had glimpsed from an airplane window during her recent international travels. As O’Keeffe painted these ethereal visions from above the clouds, she frequently hung them on her sitting-room walls. When journalist Ralph Looney visited the artist in 1962, Sky with Flat White Cloud (1962) graced one of the sitting-room walls. O’Keeffe reported that she had even considered painting the composition directly on the sitting room walls as a mural, but decided against it because it “would take too much time.” (2)

These abstract, airplane window–inspired visions coincided with a period in which the artist was enlarging several windows at both Ghost Ranch and Abiquiu. In 1964 (the same year that the Abiquiu window was created), O’Keeffe hired her old friend Maria Chabot to renovate her kitchen at Ghost Ranch and install a wraparound corner window in a new breakfast nook. Whereas the new kitchen windows opened up a dramatic, panoramic view over the mesas of Ghost Ranch, the Abiquiu window tightly frames the tamarisk tree outside in a way that is more atmospheric than expansive. Nonetheless, like O’Keeffe’s vision of a sitting-room mural from “above the clouds,” the window creates a feeling of spaciousness that alters the experience of the room.

REVELATION 2: THE NEW SITTING ROOM WAS DESIGNED TO BE PHOTOGRAPHED.

Photographers and journalists had been coming to O’Keeffe’s Abiquiu house since she had moved to New Mexico permanently in 1949, but the 1960s marked a shift in how the artist and her home were represented in print. Earlier print coverage of O’Keeffe’s homes had focused on their functionalism and eclecticism—usually highlighting their exteriors or framing tight interior close-ups. But by the mid-1960s, O’Keeffe’s interiors were held up not just as emblematic of the artist’s personal taste but also as fashionable, stylish, and even aspirational for a larger reading audience.

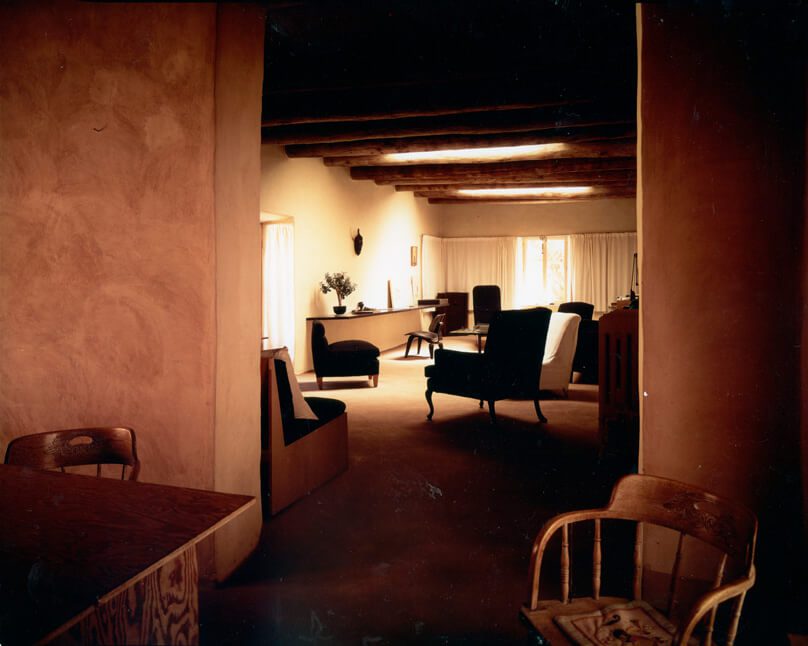

This transition is most evident in architectural photographer Balthazar Korab’s dramatic color images [reproduced here in grayscale] of 1965 for House & Garden: generous wide-angle shots open up the interiors of the Abiquiu house, showing interior landscapes as colorful and composed as O’Keeffe’s paintings. Korab later described the house as “adobe combined with hard-edge modern, chairs by Eames, Saarinen, Bertoia, Navajo rugs and her loved collection of stones, bones and roots. […] I was shooting away, without as much as moving a chair. Everything was right in place….” (3) The addition of the sitting-room window was key to this effect, fundamentally transforming the feeling of the space from cozy and cave-like to open and airy. Photographs taken through the 1960s and into the 1970s document how the furnishings, wall color, and overall atmosphere continued to evolve—yet in each of these images, the dramatic window and the tamarisk tree beyond remained essential to the total impression.

REVELATION 3: ALEXANDER GIRARD PLAYED A MAJOR ROLE.

The 1960s also marked a period of close friendship between O’Keeffe and designer Alexander Girard and his wife Susan. During this decade, the artist spent many evenings and holidays at the Girards’ Santa Fe house. Their rambling adobe home served as both a display space for their collection of international folk art and a showcase for midcentury-modern design pieces created by friends such as Ray and Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen. Most significantly to my architectural sleuthing, the house featured a generous picture window that looked out over a courtyard with a tamarisk tree. It’s not too hard to imagine O’Keeffe comfortably ensconced on the banco abutting this window after a dinner party, watching the evening light fade over the courtyard and thinking such a vignette might also enhance her own living space.

It also wouldn’t be far-fetched to think that perhaps the Girards may have made a similar suggestion during one of their frequent visits to Abiquiu. Their correspondence indicates that during their regular trips to New York, “Sandro” and Susan regularly sourced designer textiles for O’Keeffe and even helped her acquire a second Eames side chair after she enjoyed her first one so much. Girard’s design influence is undeniable in the Korab photographs, which show the newly renovated sitting room bedecked with bright, folk-inflected pillows. The complete midcentury interior shown in these 1965 images reads as Girardian maximalism tempered and restrained by O’Keeffe’s more minimalist tendencies.

REVELATION 4: O’KEEFFE AS ENTERTAINER.

Contrary to O’Keeffe’s reputation as a hermit, the artist hosted many lunches and dinners at her Abiquiu house. Indeed, O’Keeffe’s diverse social circle in the 1960s was a testament to her broad interest in the world around her—a group that included other artists, her Abiquiu neighbors, and even nuclear scientists. Even if O’Keeffe herself was not usually the chef of every course, oral histories from her guests agree that the meal planning was always exquisite, frequently incorporating healthy dishes prepared simply.

The generosity and ease of the meals themselves was reflected in the atmosphere of the house. Many friends who attended those events vividly remembered the artist’s sitting-room window as a place where people naturally congregated and children played before or after a meal. With screened doors to allow in fresh air, the window blurred the line between indoors and outdoors, while keeping the mosquitoes that plagued the flood-irrigated garden at bay. On the adobe ledge beneath the window, the artist-curated selections from her sizable rock collection. This was more than just a display space; some guests even remember being encouraged to “play with the lovely stones she had on the windowsill.” (4)

Like so many things O’Keeffe did, her sitting-room window brings together function and comfort, aesthetics and practicality. And though we can understand the window as an artifact of O’Keeffe’s friendships and artistic practice from the 1960s, it is also, I think, a representation of her much larger doctrine “of filling a space in a beautiful way.” In describing what might be done with this ethos, O’Keeffe included not only “how you address a letter or a stamp” and “what shoes you choose and how you comb your hair” but also “where you have the windows and door in a house.”

Notes

(1) Chris Eyre, director, Memories of Miss O’Keeffe (2017).

(2) Ralph Looney, O’Keeffe and Me: A Treasured Friendship (Niwot: Univ. Press of Colorado, 1995), 13. 7.

(3) Balthazar Korab, “A Fine Day in Abiquiu, April 1965,” personal reminiscence, August 1997. Collection of the Michael S. Engl Family Foundation Library at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Research Center.

(4) Elizabeth Bode Allred, interview with Sarah Burt, March 4, 2003, transcript, Georgia O’Keeffe Oral History Project, 11. Collection of the Michael S. Engl Family Foundation Library at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Research Center. O’Keeffe, n.p.