The Albuquerque Museum tells the compelling story of African American homesteading in New Mexico in the exhibition Facing the Rising Sun.

ALBUQUERQUE, NM—Homesteading in New Mexico was both a fruitful and back-breaking affair for many African American families leaving the American South and other eastern points during the early half of the 20th century.

Brenda Jones, a descendant of the Williams family, one of the original African American homesteaders in the Las Cruces area, says that her ancestors and other visionary Black families were finally able to create productive and satisfying lives after years of enslavement.

Ray Collins, whose grandparents were some of the first African American homesteaders in Albuquerque, adds that the day-to-day was both exciting and difficult.

“Back then life was so hard that my grandmother told us in the morning to go to the highway and try to get fresh kill, like rabbits. If it wasn’t on the side of the road, we’d have to chase them down,” laughs Collins. “We had onion sacks on our feet and not $100 Nikes.”

Jones and Collins, who recounted their unique family histories during a March 13, 2022 panel discussion at the Albuquerque Museum, are part of an under-told history of New Mexico’s homesteading families, who settled in Albuquerque, Blackdom, Las Cruces, and Vado (located in unincorporated Doña Ana County between Las Cruces and El Paso, Texas) starting in the early 1900s.

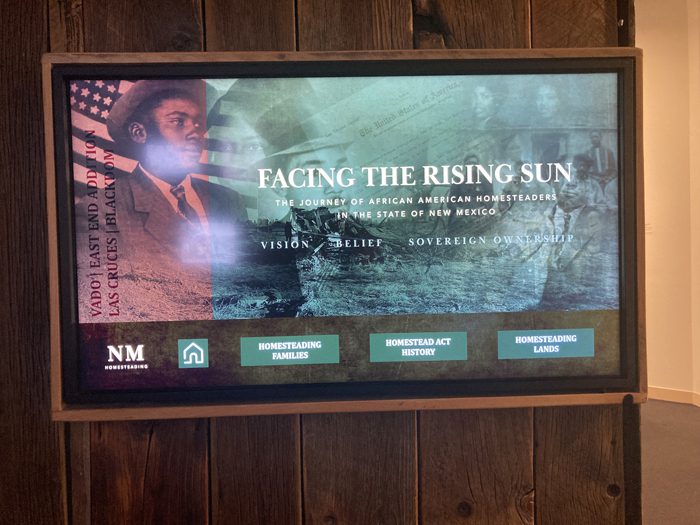

Facing the Rising Sun: The Journey of African American Homesteaders in New Mexico, Vision, Belief, and Sovereign Ownership, an exhibition currently on display at the Albuquerque Museum, highlights visionary Black families (with last names such as Boyer, Fuller, Holsome, and Pettes) who built homesteading communities full of ingenuity, business sense, and economic success. The first-of-its-kind exhibition is scheduled to remain on display through July 10, 2022, presented in partnership with the African American Museum and Cultural Center of New Mexico and the City of Albuquerque Department of Arts and Culture, and featuring design and fabrication by Albuquerque-based Electric Playhouse.

After president Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act in May 1862, which gave away many traditional and treaty lands of Native Americans, United States citizens and future citizens were able to purchase up to 160 acres of cheap land. With the Homestead Act of 1866 and the 1869 passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, which granted citizenship to newly freed African Americans slaves, Black families were encouraged to participate in homesteading ventures.

According to exhibition materials, the acreage allowance in the West would increase to 320 acres and then to 640 acres, and families could do whatever they wanted with the land.

That all sounds like utopia. However, according to family descendants, it was nothing like setting up shop today with modern conveniences at the ready. Sometimes, homesteaders were usurped by railroad companies, who often snatched the choicest parcels, leaving families with land that wasn’t arable. This was problematic because the Homestead Act required families to live on their land and grow crops for five years. In order to make money, some citizens of Blackdom, perhaps the best known of the African American homesteading communities, found jobs in neighboring Artesia.

In spite of the hard living, homesteading allowed Frank and Ella Boyer, who helped establish New Mexico’s first African American settlement Blackdom in 1903, to live autonomously. The exhibition explains that Blackdom, which was located in Chaves County in the southeastern part of the state, was often omitted from mainstream maps, allowing Black families to go unnoticed in a territory that adhered to Jim Crow laws. (New Mexico became the country’s forty-seventh state in 1912.)

More settlements popped up across the state, according to the Facing the Rising Sun exhibition, which chronicles the journeys of these families through historic maps, digital displays, and a sixty-minute film of the same name.

The Boyers, who left Blackdom in the 1920s due to a lack of water, found success in Vado, a thriving African American community of more than 500 people. The Holsome family started a 640-acre settlement outside of Las Cruces under the 1916 Homestead Act while the Collins family helped establish Albuquerque’s East End Addition starting in 1917. Down the line, the Lewis and Glover Ballou families helped the East End Addition flourish while the Pettes and Williams families contributed to the Las Cruces-area plot.

The exhibition has been met with a bit of controversy. According to a Santa Fe New Mexican report, Timothy E. Nelson, a New Mexican historian who has published in-depth research on Blackdom, resigned from New Mexico’s Black Education Act Advisory Council in January 2022. Nelson claims that the Albuquerque Museum and the New Mexico State University Art Museum in Las Cruces had both failed to give him credit for his research that was used in Facing the Rising Sun and artist Nikesha Breeze’s Four Sites of Return: Ritual, Remembrance, Reparation, and Reclamation exhibition at NMSU.

Though sites such as Blackdom are long abandoned, family legacies endure. The grandchildren of James Williams, who became a spokesperson and civil-rights activist for the Negro Homesteaders, can still lay claim to a majority of the 640 acres that Williams settled near Las Cruces. And the grandchildren of Robert A. Pettes and son Grover, who went on to establish a water utility company later named Mesa Development Center, Inc., retain ownership of some of the land in southeastern New Mexico.

Facing the Rising Sun: The Journey of African American Homesteaders in New Mexico, Vision, Belief, and Sovereign Ownership is scheduled to hang through July 10, 2022 at the Albuquerque Museum, 2000 Mountain Road NW.