Images in Silver begins with a quote from famed French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. “Photographers deal in things which are continually vanishing,” it goes, “and when they have vanished, there is no contrivance on earth which can make them come back again.” Photography, then, is a managed slice of time. Bounded by a frame, light and form are mingled and distilled. The end result is something more substantial than a passing moment. We might construct a narrative around a picture in our imaginations, but in the object itself there is no before or after, there is nothing outside the frame.

In this beautifully compiled collection of 180 photos from the more than 130,000 contained within the Albuquerque Museum collection, longtime archivist Glenn Fye has condensed the museum’s repository down to a little more than 200 pages, arranged in sections that showcase the work of three commercial studios, and three independent, amateur photographers. The subjects vary tremendously—there are ghostly portraits of those once young and lively, whose stares conjure something like memento mori; a large collection of early aviation photographs; striking cityscapes that are just barely recognizable; a patient’s humble quarters in a sanatorium; and trains idling through town with smoke drifting up into the cloudless desert sky.

The choice to preface the collection with a thought from Cartier-Bresson is apt. Cartier-Bresson’s romantic philosophy of the art of photography hinged largely on finding and capturing the perfect moment, in which all external forces take harmonious shape. He posited photography as reactive, as “presentiment to the way life itself unfolds,” seizing passing beauty and holding it. Here hundreds of distinct, fleeting moments create an aura of stratified time—our lives are playing out here on the very same Albuquerque city blocks, and even within the same buildings as these people. Though our time and theirs is spread out across a vast timeline, our physical place is the same. These photos are quite literally the presentiment, the anticipation, of ourselves and the city as it stands around us now.

There is precious little text in Images in Silver, beyond the necessary blips of context, and a few pages of words by former archivist Mo Palmer and former curator Byron A. Johnson, with a foreword by current museum director Cathy Wright. This move allows the images themselves greater primacy and for the book as a whole to avoid some of the nostalgia that is often difficult to sidestep in broad, historical collections such as this.

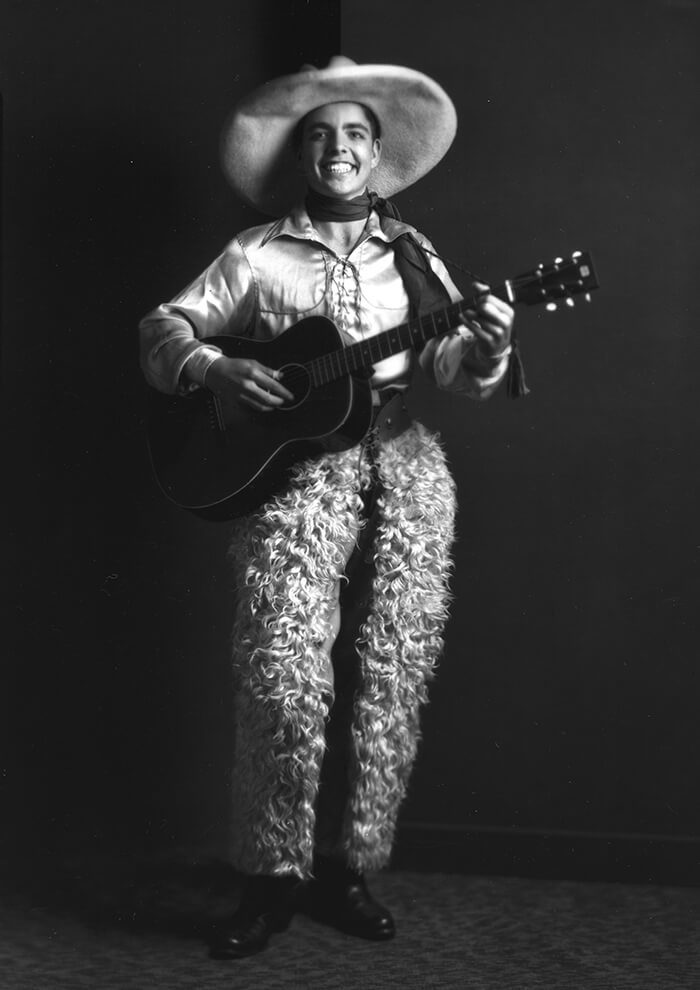

What resonates with me most are the portraits contained within the book—and there are many—containing bygone fashions and the particular affects of the times. I recognize the careful posturing, with each element well chosen. In our experience today “everything exists to end in a photograph,” as Susan Sontag put it. The ubiquity of photography has only exacerbated the act of performing for the photo. We see that staged quality plainly in these markedly less casual photographs. Though decades removed, we perceive certain enduring qualities underneath the ’30s-style bobs and pin curls, or smart newsboy caps, though the contexts for the medium and the way it is understood have changed dramatically.

While image doesn’t necessarily equal truth, as Johnson points out in the opening essay, these pre-digital photos also do the work of filling in the thin record of the time—cataloguing the city even as it was in the midst of change. They offer a visual account of a time and place ever in flux.

There are so many beautiful words that have been written about photography that speak to what it feels like to flip through Images in Silver, wherein so much is familiar—the KiMo, a stretch of Second Street—and yet out of reach. “The photograph repeats what can never be repeated existentially,” Roland Barthes wrote in Camera Lucida. That reiteration of the march of time—the reminder of death and change ever on our heels—is important to return to often. Just so, it is moving to peer into this collection in order to remember the full latitude of time and its passage.