When the Lubbock City Council defunded a popular art event for promoting the “LGBT Agenda,” confirming fears of repressive drag bans in Texas, the art community got fired up.

This summer was a hot one in Lubbock, Texas—and not only because of the triple-digit temperatures. Between righteous “undrag” queens with tempers flaring and the fiery rhetoric of the “family-values” set, the heat was enough to make you lose your wig.

First, there was an uproar within the LGBTQ+ community, claiming that a drag show was censored by the Charles Adams Studio Project at the city’s popular First Friday Art Trail event on July 5, 2024.

Then, on July 23, a Lubbock city councilman moved to strike the funding for FFAT from the Civic Lubbock Cultural Arts Grants, citing a “broader trend across the state” of “sexualized LGBT events” that “target children” and should not be funded by public tax money.

In the middle of the fray is CASP and the Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts, the two major entities that make up the beating heart of Lubbock’s arts district—who are accused on one hand of censoring drag performances, and on the other of promoting them. The resulting fracas—over art and expression, public funds and censorship—demonstrates the ways that political rhetoric can cast a shadow over culture, creating a chilling effect and an atmosphere of fear that disproportionately affect marginalized communities.

This story begins, however, back in May 2023, when the Texas legislature, along with six other bills targeting the LGBTQ+ population, passed Senate Bill 12, the so-called “Drag Ban Bill” that would prohibit “sexually oriented performances” in the presence of minors.

On June 18, Governor Greg Abbott signed the bill into law, which would have gone into effect September 1, 2023, carrying with it up to $10,000 in penalties for any performance perceived as “sexual” in nature, and granting cities and counties the ability to regulate and ban such performances.

The vague language of the bill targeted drag performers by outlawing “accessories and prosthetics that exaggerate… sexual characteristics,” but could also be applied to a wide range of gestures, dance moves, and costumery.

Following the passage of the bill, actors, dancers, performance artists, drag performers, arts organizers, and educators were left in a state of panic and uncertainty.

Following the passage of the bill, actors, dancers, performance artists, drag performers, arts organizers, and educators were left in a state of panic and uncertainty.

In August 2023, after the ACLU filed suit, a federal judge issued a temporary restraining order preventing the law from going into effect. On September 26, SB 12 was ruled unconstitutional.

“We were watching [the situation around SB 12] closely,” says Budd Dees, who is the entertainment coordinator for Lubbock Pride and a drag artist, performing as Cindi TV. This year’s Pride took place on the grounds of LHUCA and featured a drag show. (Unlike First Friday, which is free and open to the public, Pride was a ticketed event, in part due to security concerns.)

Many folks in the art community that I spoke to, however, were unaware of the ACLU lawsuit and the judge’s ruling against SB 12, and were under the impression that its $10,000 fine was enforceable.

To make matters more confusing, ahead of the July First Friday event, rumors had circulated about a local community art space being forced to close and served with a fine for hosting a drag queen story hour. According to executive director Lindsey Maestri, LHUCA and CASP had both received text messages from “leaders in the queer community that we trusted” that the City might be in the process of issuing fines for drag performances.

So when Chad Plunket, the director of CASP, heard that a drag performance was scheduled to take place at CASP’s 5&J Gallery on First Friday—part of a group show entitled Madres Radicales, which sought to “expand traditional narratives about madres/mothering”—he tried to pull the plug on the drag component of the performance.

“I cannot believe I’m having to write this. I was just informed that based on SB-12 that having drag performances will not work. […] this is an attack on… freedom of speech,” wrote one of the exhibition curators, Katy Ballard, to the performers via group text message, according to a statement. This was just moments before thousands of visitors would start to flood the Plaza for the monthly art celebration.

Dees, who was preparing for a performance as Cindi TV replete with a rig that would have transformed him into a “walking projector screen,” was already in full makeup when he got the news. “I was planning these two incredibly ambitious numbers,” he says, describing how his performance would relate to the theme of the show, referencing ideas about drag mothers and chosen families. “I was really thinking about this as a sculptural performance art thing that just happened to be intermingled with drag queens,” he says.

Dees and Ballard even contacted Austin-based drag queen Brigitte Bandit, the plaintiff in the ACLU case, to bolster their argument that SB 12 had indeed been blocked by a federal judge. Plunket pointed to the fact that the law is still on the books, texting Ballard about an hour before FFAT started, “SB 12 is currently state law. To ensure the safety of all participants tonight, CASP cannot allow drag queens to perform during FFAT.”

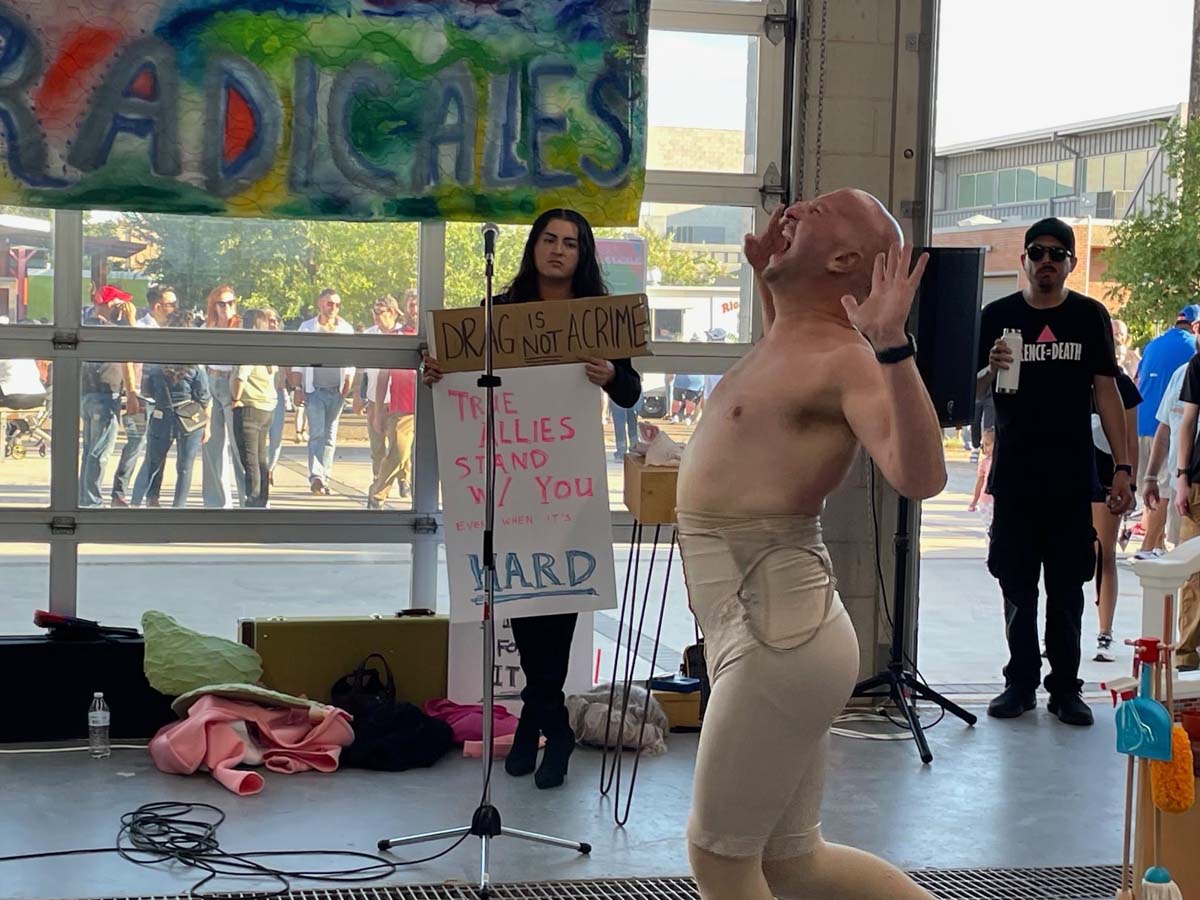

Some of the queens decided not to show up in light of the cancellation. Others, including Cindi TV, Jaxxon Swallows, and Donabela D’Angelo, still wanted a payoff for their hours of makeup, and came to First Friday holding signs reading “Drag is Not a Crime” and “True Allies Stand W/ You, Even When It’s Hard.”

In a decision made moments before the scheduled performance, the performers struck a compromise allowing them to take the stage, but out of drag. By de-dragging, they were essentially trying to sidestep what SB 12 had supposedly criminalized.

I was basically just there in tights and a leotard; I even took off my high heels. I’m getting as far away from drag as I possibly can.

At 5&J Gallery, as the music played, Cindi TV and Donabela D’Angelo took off their wigs and their makeup, removed costumes and padding. “I was basically just there in tights and a leotard; I even took off my high heels,” says Dees. “I’m getting as far away from drag as I possibly can.”

Stripped of any accessories or props, lip-syncing to a revenge-laden song by Lingua Ignota that took on new layers of meaning given the circumstances, Dees delivered a powerfully raw, “undrag” performance that night. Dees reflects, “I was in the mood to give it, so I gave it!”

A statement issued on July 21 by the curators of Madres Radicales gave an account of the dispute and the decisions made that fateful Friday night. Posing such questions as “Who is an ally?” and “How do we support each other?” the statement concludes: “It may be tempting for some to sweep this to the side and dismiss the whole ordeal from July 5th as a misunderstanding, a mere impulsive decision on the heels of fear. Although this may be in part accurate, the harm was done resulting in traumatic realities that will not be forgotten. We have a responsibility to speak up for each other.”

Speaking later with the curators and exhibition organizers, all described the atmosphere that night as extremely tense and angry. Some, like Ballard, claim Plunket’s decision to cancel the drag performance amounted to censorship, driven by misinformation and fear. “We were all in a shit position, and it’s because of a bigger problem,” Ballard told me. “This is about censorship; this is about anti-LGBTQIA artists and lives and any marginalized group that could get attacked.”

When asked about the decision to cancel the drag show and the ensuing fallout, Plunket paused before responding, “I think when you invite the public, you invite your community to your event, your basic number one responsibility is the safety of everybody—performers, artists, staff, and the people coming.” He continued, “On July 5, I had too many questions to say that 5&J Gallery was the right place to do those performances, and so when I said we can’t do this, I did that with a variety of issues swirling around in my head. It certainly hurt when people showed up and protested.”

Ballard, an artist and curator now based in Taos, New Mexico, has deep roots in West Texas and wrote her PhD dissertation on oral histories of drag queens living in Lubbock. She wonders, “How did [Plunket] expect the performers react? We’re talking about marginalized queer performers who are already getting shit on and the fact that laws do exist to keep them from performing.”

I think people were really upset because people thought this was a safe space for us, and the entire First Friday… is a meaningful project for a lot of queer artists.

Immediately following First Friday, many members of the LGBTQ+ community rallied behind the drag queens on social media. Dees says, “I think people were really upset because people thought this was a safe space for us, and the entire First Friday… is a meaningful project for a lot of queer artists.”

A few days after the First Friday fiasco, Plunket, Maestri, Dees, and Scotty Hensler, an artist and exhibition coordinator for Madres Radicales, met to clear the air and find a path forward for LHUCA and CASP. They made a plan and contacted the ACLU and other organizations for legal advice on SB 12 and other local laws that might affect drag performances.

After the meeting, Dees wrote on Facebook: “I believe that all people at the meeting are genuine and well-intentioned actors… and support and affirm LGBTQ+ expression. […] We all agreed that we would like to make decisions based on legal reality, and not rumors.”

What they didn’t know, however, is some powerful actors on the other end of the political spectrum were watching.

Reflecting on what happened next, Dees told me, “The thing that I didn’t really anticipate is there are many other ways to punish drag queens for performing or to punish venues for allowing drag queens to perform.”

On July 23, the Lubbock City Council, in a surprise decision and without seeking public comment, voted to pull up to $30,000 in Hotel Occupancy Tax funding from LHUCA for their operation of FFAT.

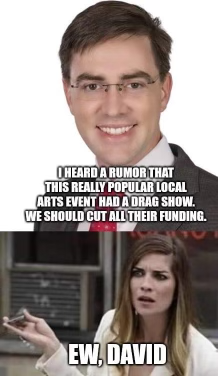

Councilman David Glasheen, who took office in June 2024 after running unopposed for the nonpartisan seat, moved to strike the funding from a grant already approved by Civic Lubbock, Inc., the nonprofit body that administers the HOT funds, which are earmarked for projects that promote tourism and encourage the arts and humanities in Lubbock. The motion to deny funding was an unprecedented move by the City of Lubbock, which—like most municipalities in Texas—generally rubberstamps the grants approved by contracted organizations like CLI.

Councilwoman Christy Martinez-Garcia, who represents the district containing downtown Lubbock, where FFAT takes place, was visibly surprised by Glasheen’s remarks in the meeting.

Glasheen argued that FFAT “promot[ed the] LGBT agenda” through events like drag performances, Lubbock Pride, and a “child-friendly LGBT workshop” that was part of a June exhibition entitled Queering West Texas. “The intention is to offer full drag performances on the Art Trail in the next year,” he stated. There is no evidence for Glasheen’s assertion of LHUCA’s intention to hold drag performances as part of their programming anywhere in their application for the Cultural Arts Grant.

Martinez-Garcia responded in defense of FFAT, bringing up its role in downtown development and the growth of the city. She said, “As this city grows and as the interest of the city to build up downtown I think we need to make it open to everyone and everybody.”

Other council members, unlike Martinez-Garcia, did not appear surprised by Glasheen’s motion. The newly elected mayor Mark McBrayer jumped in to say, “I understand exactly where Mr. Glasheen is coming from.” He agreed, using language that seemed to come straight from SB 12: “The fact of the matter is drag queen performances are sexualized. We have no business spending tax money promoting that to an event that’s supposed to be… family friendly.” McBrayer claimed FFAT programming choices represented a “slippery slope,” stating: “I support the use of this money to enhance our cultural activities in Lubbock but people who do this need to… take the temperature of the community in which they exist.”

After a very brief discussion, the council voted five to two to withdraw the grant from FFAT, allowing it, in one councilman’s words, to “operate without the burden of public funds.” Martinez-Garcia and Councilman Gordon Harris were the two dissenting votes.

Following the decision, Martinez-Garcia placed a resolution on the City Council’s next meeting agenda to reconsider the funding. She later told Texas art publication Glasstire, “I believe the public should be concerned that our dais has been compromised by partisan politics.” Martinez-Garcia also pointed out that “LHUCA is being held to a different set of standards despite following the same guidelines as all the other groups that also applied for the grant funds because of false information.”

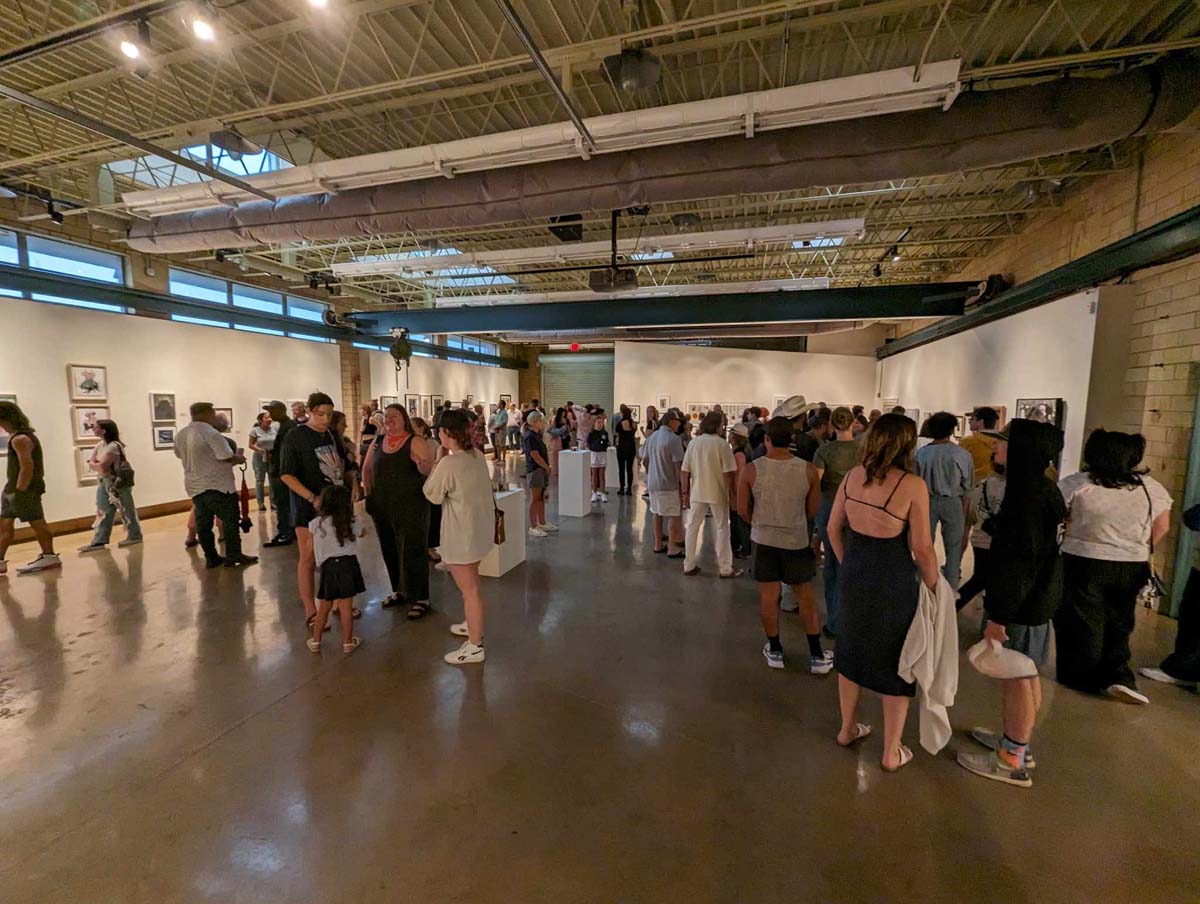

Lubbock’s FFAT, a program of LHUCA that just entered its twentieth year, attracts a staggeringly large audience for art, constituting a broad cross-section of Lubbock residents and visitors: around 5,000 to 7,000 attendees to LHUCA’s Plaza on any given night. In addition to the main art center, LHUCA, there are galleries, CASP artist open studios, craft vendors, food trucks, bands, dance performances, free trolleys bringing people to other venues on the trail, and ample people-watching opportunities. First Friday seems to be continually expanding.

Chris Kiley, the executive director of the nonprofit, nonpartisan arts advocacy organization, Texans for the Arts, holds up Lubbock’s FFAT and the city’s arts district as a “role model” for the successful use of HOT taxes to bolster tourism, growth, and support for the arts. “The economic impact that that one monthly event has is huge,” he says. “And not just for the arts, right? There’re food trucks and other vendors that are out there, and restaurants are busier, and people are coming far and wide, not just from Lubbock.”

A city of around 250,000 on the High Plains of West Texas, home of Texas Tech and music legend Buddy Holly, Lubbock has a unique history. Much of its downtown was destroyed in a tornado in 1970, so Lubbock’s downtown arts district occupies a space that feels more like a ghost town than an urban center most days. Over the last twenty years, downtown revitalization has finally started growing, due, in part, to efforts like the downtown arts district bringing visitors and businesses to the area.

Given FFAT’s popularity in the city, its identity as a keystone art event across the greater West Texas region, and the significant revenue it brings in, many were surprised to find it under attack by the City Council. “The investment and the monetary return that comes from First Friday—it’s huge,” says Maestri. “Cities should be supportive of something that is bringing in that much revenue.”

“Generally speaking, it is very rare if funding is recommended by an organization like Civic Lubbock for the City Council not to make their approvals,” Kiley says.

The Cultural Arts Grants that are funded through a portion of the city’s HOT taxes are awarded each year to eligible projects that do two things: promote tourism and the hotel industry, and encourage the arts and humanities. Besides outlining the major art forms—music, dance, drama, visual arts, etc.—there are no stipulations about types of art, content, nor a requirement that the projects must be “family-friendly” or suitable for certain audiences.

LHUCA applied for the grant funds, which cover between 25 and 30% of the budget of FFAT, to use for security, trolleys, signage, marketing, and musician and artist fees. The application did not contain any information about specific programming or content, and in fact, of the exhibitions and events that Glasheen had brought to the City Council’s attention, none had been funded through that grant, none had taken place within LHUCA’s purview, and some hadn’t even occurred on a First Friday.

In a statement released following the City Council vote to defund FFAT, LHUCA stated, “the programming in question was not held on LHUCA property but rather at [a] separate entity in control of their own creative programming.”

It’s been awful. And it’s awful that they came so directly at the LGBTQ content.

“It’s been awful,” Maestri told me shortly after the July 23 City Council meeting. “And it’s awful that they came so directly at the LGBTQ content.”

Maestri found the subsequent outpouring of support and calls for donations from the community encouraging, however. Asked how she gauged the “temperature” of the community, Maestri said, “I feel like the temperature is supportive of the arts, supportive of progress in downtown, and we are really proud of the vibrant parts of our community and the community definitely feels protective of them.”

Artists made posters, t-shirts, and postcards; a petition was circulated; folks wrote letters to the mayor and their council members. LGBTQ+ leaders and rights advocacy organizations, like Human Rights Campaign, spoke out. People switched their social media profile pictures to show their support and posted under the hashtag #lbkloves. A local business offered proceeds from taco sales to donate to LHUCA. Accounts of the August 2 First Friday attested to soaring attendance numbers, particularly high for such a brutally hot summer night.

Likewise, the August 13 City Council meeting drew a crowd, exceeding the seating of the hall. Nearly sixty Lubbock residents voiced their support for LHUCA, and urged the City Council members to reconsider funding for First Friday. A handful of commenters applauded the City for their decision, and a couple spoke on other topics. But for about three hours, the Council sat and listened to testimonial after testimonial about the value of the Art Trail from artists, vendors, professors, parents, and LGBTQ+ community members.

One impassioned speaker even invoked the “ghost of Louise Hopkins Underwood,” the namesake of LHUCA, to “haunt you until you make the right decision!” Mayor McBrayer did not appreciate this rousing speech and lectured the entire hall for applauding it.

One speaker, who identified as a gay man, related how he grew up mocked and bullied, left Lubbock for twenty-five years, and came back to find that the city had progressed. He said he was finally happy here. “I think your actions have erased much of this,” he stated. “Lubbock, this is what happens to you when 8% of you turn out to vote. This is what you get.”

For about three hours, the Council sat and listened to testimonial after testimonial about the value of the Art Trail from artists, vendors, professors, parents, and LGBTQ+ community members.

Another implored one of the council members, a pediatrician, to acknowledge the higher rate of suicide among LGBTQ+ youth who don’t feel accepted.

In the discussion of the agenda item by the Council, Glasheen appeared to walk back some of his initial anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment, saying, “This is really not even just a LGBT issue, it’s about a broader question of what are some common-sense restrictions on the types of expression that should be supported or promoted by tax dollars.”

Martinez-Garcia countered that the motion to defund First Friday was based entirely on social media and hearsay. LHUCA followed the process, she said, “it is not fair that we hold them to a different set of standards.”

McBrayer pushed back against the notion that the Council was seen as “anti-art.” “We are not censoring artists,” he insisted, claiming, “artists are free to express themselves wherever they want to; they don’t have a right to expect taxpayer money to support everything and anything they do.”

The Council held another vote over the full amount of the funding, which failed (one other council member, Tim Collins, flipped his previous position to support LHUCA). They then debated the issue of public safety, and whether some portion of the grant could be approved, for the trolley service and for security. This failed again.

Finally, McBrayer, who campaigned on a platform of no new taxes, but supports a higher police budget, cast the deciding vote to grant FFAT $5,000 exclusively for security, which goes to pay off-duty police officers for the event. “I think the security aspect of this may be something that we need to think somewhat carefully about,” he said, noting that, “because of the temperature that has been increased, I’m concerned about how things might play out at the First Friday Art Trail going forward, and I’m concerned about our responsibility to them for that.”

On a weekday visit to LHUCA following the City Council meeting, the main hall was empty, but for a 1,260-square-foot piece of white silk billowing overhead in a wave pattern driven by high-powered fans, an installation by Abi Ogle titled Metronome. I overheard the gallery attendant answering a phone call. Yes, First Friday will still be happening, she confirmed, but there might not be trolley service in the future.

Among artists and gallery owners I spoke to, some expressed fear resulting from the targeting of First Friday, and the threat of potential violent backlash—an ever-present concern at any high-profile event, now perhaps looming even larger.

Many, including Dees, feel defeated and saddened by the process the art and LGBTQ+ communities went through with a political majority in city government that at best seemed indifferent to their pleas, at worst, hostile to them. “To explicitly remove funding because of LGBTQ programming seems really targeted and discriminatory,” he says. “It felt like, we’re going to perform this law [SB 12] by other levers of power that we can manipulate.”

Maestri expresses frustration at the position LHUCA was thrust into. “We always feel like we’re under a magnifying glass in some way in the arts,” she says. “Even though [SB 12] had been stayed by a judge, we knew that [Texas Attorney General] Paxton is looking for a way to bring it back up.”

Some, like Melodía Gutiérrez, the Texas state director of Human Rights Campaign, who is based in Lubbock, see the decision to defund as a harbinger of things to come. “It’s unfortunate that the Lubbock City Council is preemptively implementing something that’s not the law of the land,” she says, pointing out that drag performance is a protected form of free speech, and efforts to restrict it amount to discrimination. “It’s unfortunate that they are taking this route for something that is so inclusive, safe, and special and turning it into something that is grossly mischaracterizing our community.”

“Putting drag performances and other LGBTQ+ content-based performances in a category that it is ‘inappropriate’” is wrong, she says. “There’s nothing inherently adult or obscene about drag performances or art that upholds LGBTQ+ visibility. They [City Council] are coloring outside the lines in a really dangerous way here.”

Lubbock, the tenth-largest city in Texas and considered a conservative stronghold in the majority-red state, sometimes acts as a staging ground for conservative policies, particularly those favored by right-wing Christians. In 2021, Lubbock was the first major Texas city to pass a “Sanctuary City for the Unborn” ordinance banning abortion within city limits, anticipating the statewide ban, and ahead of the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade. Gutiérrez points to such examples of “hyperlocalized battles that then build a trajectory into the [state] legislative session.”

On September 6, First Friday arrived yet again with its usual carnivalesque atmosphere. Food trucks with noisy generators, a rock band on the Plaza stage, families with strollers, folks posing for selfies in front of artworks, and young people dressed to the nines. Gallery 5&J, marking its 15th anniversary, was filled with booths for its annual printmaking fair. Someone on the street held a small handwritten sign saying “Free Dream Interpretations.”

When we talk about community, it’s because you show up. […] And, like, that’s real, and I can’t do that on social media. You have to come, you have to be present.

“Our whole thing is: you have to be here,” says Plunket. “When we talk about community, it’s because you show up and we say hi and we shake hands or this guy I fist bump and this person I give a hug. And, like, that’s real, and I can’t do that on social media. You have to come, you have to be present.”

A widespread criticism of Glasheen’s objections to First Friday is that he took offense to exhibitions and performances that he learned about only through social media, experienced only through the prism of conservative outrage. Other council members, including the mayor, have professed to “love First Friday” and “support the arts,” claiming that their actions are not political but rather about policy.

“We talk a lot about inclusivity,” McBrayer said in August, “This is taxpayer money, and so what we want [it] to be used for is something that is inclusive of as many people in our community as possible.”

When confronted with the fact that the exhibitions and drag performances that Glasheen brought up in the initial move to defund FFAT hadn’t taken place on LHUCA grounds or were funded by HOT tax, Glasheen told KCBD, “It doesn’t matter who owns the building. There is no dispute that drag performances took place at a First Friday Art Trail venue and so there has to be accountability for the public that is being used to advertise and promote the First Friday Art Trail.” Glasheen did not respond to multiple requests for an interview with SWC.

Maestri says that LHUCA was able to offset the funds lost from the grant using a surge of community donations following the City Council decision, and saw a rise in their museum memberships. They are actively seeking out other grants and fundraising sources, and seeking an underwriter or partnership to continue the trolley service into the future. Civic Lubbock confirmed that the grant funds denied to LHUCA will simply roll over into the next year’s budget.

Ballard and her collaborator Daniela Cervantes are currently producing a short documentary about Madres Radicales and the night of July 5. “There is a lot of support for LHUCA mixed with an understanding that it was a hard situation for everyone,” she says. “We also learned that there is a deep understanding of the power of art and community.”

The community is still simmering. Multiple people involved with First Friday describe it as a “thankless” endeavor—a lot of work and care was invested in its production and execution, only to be met with knee-jerk politics.

Despite the divisive outcome, the overarching effect of the controversy appears to be a freshly fired-up art community in Lubbock, as artists, arts organizers, and allies entered civic spaces to demonstrate their defiance, resilience, and creativity.