“All my dances are protests,” says one artist from Movements Toward Freedom, a group exhibition that explores how singular and collective bodily expressions can influence society.

DENVER—Brendan Fernandes calls over a small group of dancers to look at his phone. He says he wants to do something he calls “building monuments.” They’ll sequentially construct a living tableau with their bodies, Fernandes explains. One by one the dancers begin to build, the first establishing the foundation.

“Then think about, where do they need support?” Fernandes says as one dancer holds up another’s arm.

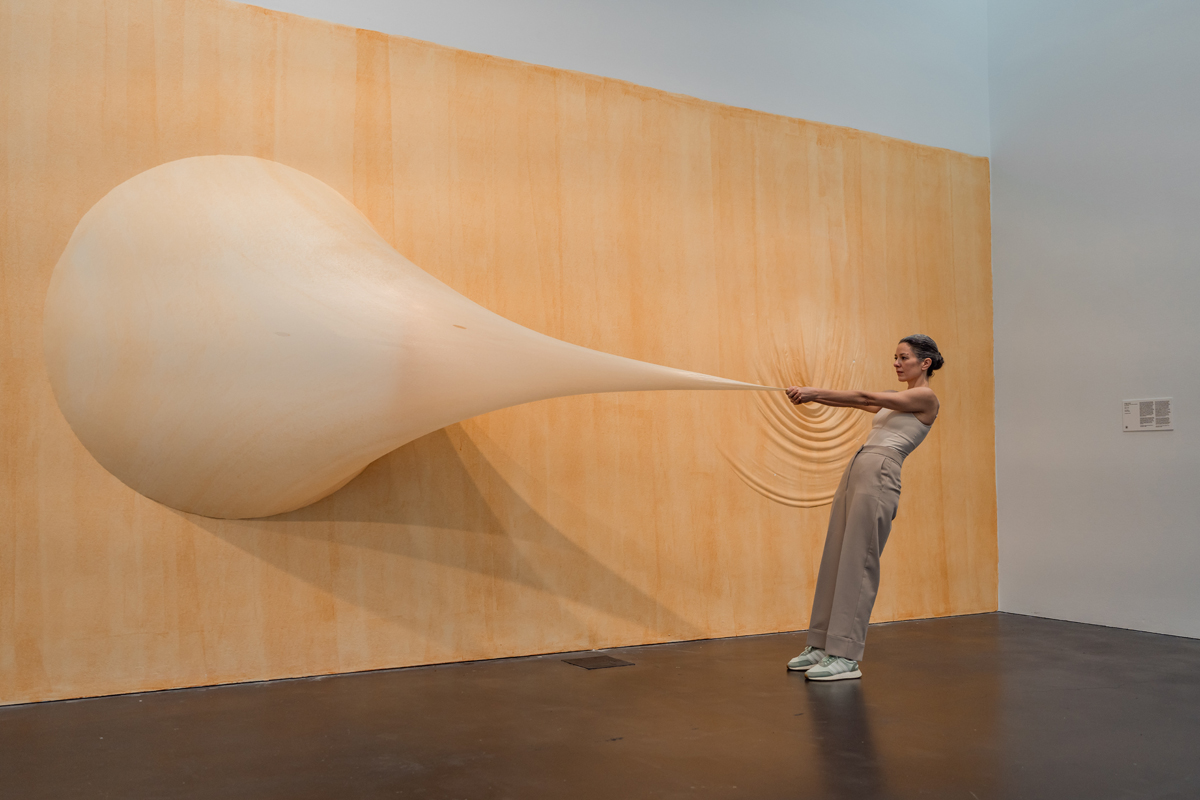

They’re rehearsing for an event tied to an exhibition on view through February 2 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. Movements Toward Freedom connects the physical and social definitions of the word movement, ranging from reflections on concert dance like ballet or modern to social dancing and even the fitness industry. It features work from twenty-one artists, who, through sculpture, video, painting, installation, and performance, examine and question bodies in motion and how the singular and collective expression of movement can impact a society.

Much of the artwork galvanizes the audience through live performance and by inviting viewers to touch and interact with it. And for artists like Fernandes, there’s always been an inherent link between dance movement, the political, and the social.

“All my dances are protests,” Fernandes, whose interdisciplinary work often weaves together dance and visual art, says. “All my dances are ways of gathering and bringing people together… and to make political movements, you need physical action. So I kind of meld them.”

Fernandes was one of the first artists MCA Denver associate curator Leilani Lynch contacted because much of his work is identity-based and steeped in sociopolitical conversations. Lynch also connected with Fernandes’s use of ballet vernacular, which she understands well due to her own rigorous ballet training.

She says her dance background lends a sensitivity to movement-based visual art practices—but it wasn’t a major impetus for this exhibition. Rather, Lynch says Movements Toward Freedom came about due to the disconnectedness many people felt after being online so much during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. The timing of the exhibition’s opening ahead of a presidential election was also top of mind.

Fernandes noticed that the museum’s floor in that area is ‘sprung.’ It’s a rare find in a museum.

“Being in this moment of anxiety, I was thinking about this as an offering and exploration of what it means to be grounded in our bodies. Then thinking about how we can move together, and how powerful and vulnerable that can be,” Lynch says.

Fernandes’s installation We came to dance is an impressionistic yet functional reconstruction of a dance studio on the museum’s basement level. Wooden ballet barres are throughout the space with prompts etched into them, like “a delicate touch” or “a subtle intimacy.” Mirrors are positioned on pedestals or hung on the walls. The studio has been a space for Fernandes to create. It’s also available for community use—a gift “that people can experiment, challenge, grow, and make within.”

The idea took shape after Fernandes noticed that the museum’s floor in that area is “sprung,” meaning it’s shock-absorbent and creates a softer landing for jumping and moving. It’s a rare find in a museum.

“For many dancers, we always think about the floor as a space of resistance,” Fernandes says. “It’s an architectural form that holds the body right, but also as we dance and labor on it… [it] can support or burden the body.” That physical resistance easily translates to political and social resistance.

As for the mirrors, Fernandes thought about how they both reflect our selves and help us learn to know ourselves: “This idea of self-respect and self-love, self-caring. Once you know how to do that for yourself, then you can… build upon that kind of nurture and kindness into a greater community base.”

One floor up, the overarching theme is “movement as memory, and joy as resistance and survival,” Lynch says. The work largely reflects on historically radical spaces for gathering and dancing. That includes Sadie Barnette’s Mirror Bar, a wall-hanging sculpture with neon, vinyl, and mirrored plexiglass that’s part of a larger project referencing San Francisco’s first Black-owned gay bar, which was run by Barnette’s father.

The same space features work by Kambui Olujimi, who was inspired by the public spectacle of dance marathons in the 1920s and ’30s, particularly after the stock market crashed. He was attracted to the “mythic space” these popular events created for participants and spectators, full of soap opera–like drama while giving voice and offering cash prizes to a population who felt disenfranchised.

You literally slept on one another. Your ability to continue is completely contingent on another body.

“The phenomena [were] extremely radical in some ways and not in others,” says Olujimi, who has long incorporated movement into his visual art practice. “There was a class excitement or liberation for white Americans who were already poor or who had become poor to have mobility and visibility.”

He was fascinated by the physical dependence dancers relied on to get through the marathons. “You literally slept on one another. Your ability to continue is completely contingent on another body,” Olujimi says.

But he points out that they were also exploitative, even referred to as “derbies” with the dancers “being treated like horses in a horse race.” There was sort of a perverse enjoyment from crowds in the suffering of others as participants danced nonstop for hours and had their lives exposed to the public. They were also segregated, like the rest of the U.S. at that time.

As Olujimi worked on the series over the last decade-plus, his interest in these dance marathons and their place in American performance history overlapped with major moments in recent history, like the 2008 recession, the first Trump administration, and the founding of the Black Lives Matter movement and BLM protests across the nation in the wake of police killings—”there’s always a voice between the historic and contemporary for me.”

Community organizer, filmmaker, mother, and dance artist Shamell Bell, who has no connection to the MCA Denver show, says bodies occupying space, whether in a choreographed dance or marching in protest, is a powerful political and social statement.

“One of my favorite things is the 5, 6, 7, 8, because when you say ‘5, 6, 7, 8,’ people know to move together in space,” says Bell, who is a lecturer of somatic practices and global performance at Harvard University.

Additionally, Bell calls movement a “healing modality.”

“Dancing as a body scan and getting you into your body and the way that you breathe, that’s what it means to be a healing modality,” she says. “So if we’re setting intentions into our bodies and out into the world, we are setting the intention to heal the world.”

Associate curator Leilani Lynch hopes that, in some ways, there is a dance between visitors and the artwork in this exhibition.

“I think this exhibition shows an interesting facet of contemporary art practice in which the artist is really interested in involving the visitor in their work,” Lynch says. “And so it becomes that duet where the art can exist on its own, but it’s also waiting for you.”