Belonging: Contemporary Native Ceramics from the Southern Plains brings together works by seven artists that range from ceramic vessels to monumental sculptures to installations that radiate outward in space.

Belonging: Contemporary Native Ceramics from the Southern Plains

February 2–March 23, 2024

Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts, Lubbock, TX

As curator and scholar of Native American art Klinton Burgio-Ericson writes in the catalogue, the work in Belonging: Contemporary Native Ceramics from the Southern Plains is not about “identity,” which “often carries a sense of choice in identifying one way, rather than others,” but about “belonging,” which centers around concepts of reciprocity and “mutual obligation.” Like a series of concentric and interlocking circles of belonging, Burgio-Ericson touches upon family, kin, tribe, culture, land, and time in his essay, through multiple works that express those connections through clay. These works range from ceramic vessels to monumental sculptures to installations that radiate outward in space.

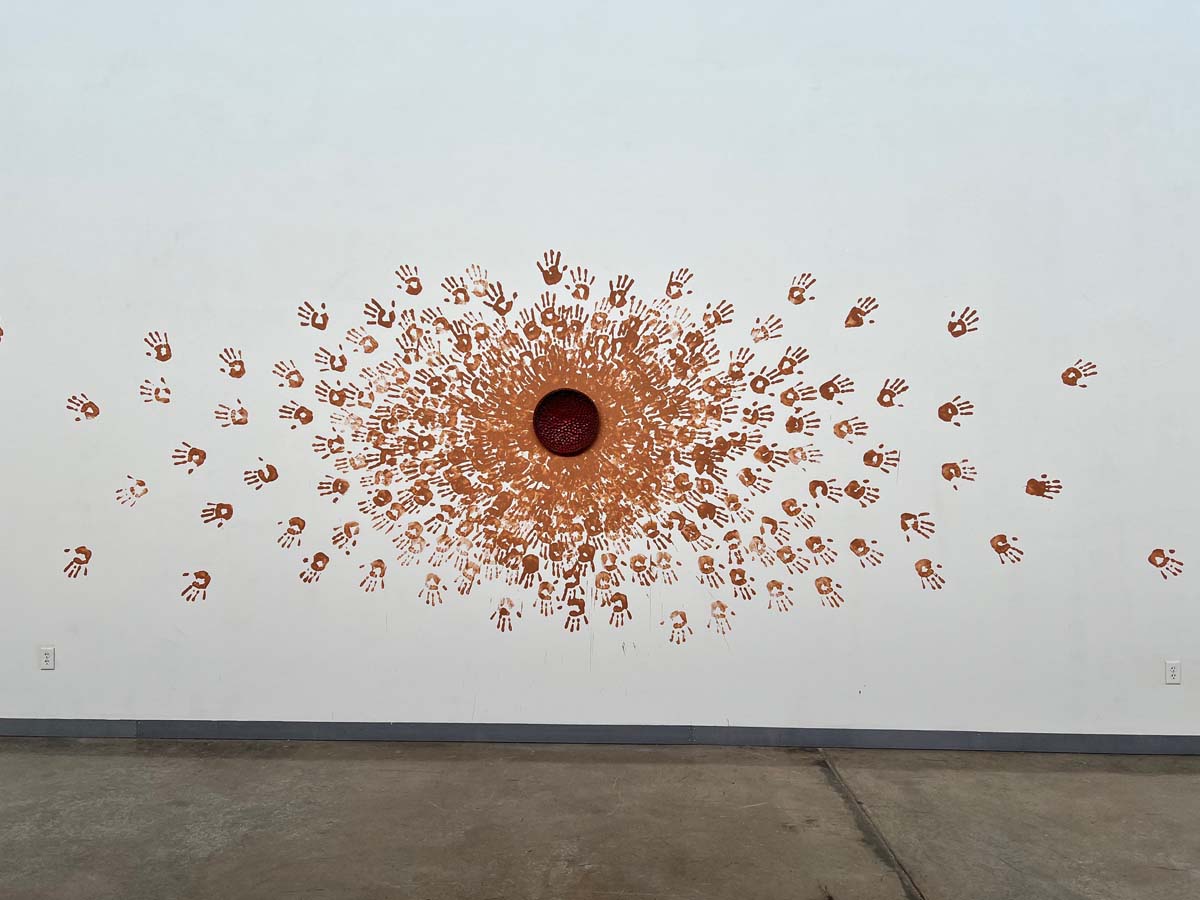

The exhibition, presented in conjunction with Texas Tech University’s 2024 Texas Ceramics Symposium, spreads across both of LHUCA’s main galleries in an evocative arrangement of the seven artists’ work. Raven Halfmoon’s (Caddo, Choctaw, Delaware, Otoe) imposing Cowgirl at Heart (2022) overlooks Anita Fields’s (Osage, Muscogee) Building Fires (2023), a naturalistic stack of clay logs like a campfire waiting to be set. On the wall, Cortney YellowHorse-Metzger’s (Osage) handprints emanate from a central red-glazed stoneware bowl impressed with the artist’s fingerprints, while Jane Osti’s (Cherokee National Treasure) squash pot Circles of Belonging (2023) is incised with flowing, layered spiral patterns, the works opening up a resounding mutual reverberation of patterns and movement that seems to echo and swirl across generations.

Different generations of contemporary Native artists are represented in this show as well. Comanche artist Karita Coffey attended the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, one of its first female students, during the 1960s, and later taught at IAIA for many years. Cannupa Hanska Luger (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Lakota) was one of her students. While his practice spans multiple media, the works on display here—high caliber bullets and gas pump handles of ceramic—may owe their high level of craftsmanship to Coffey’s instruction.

Situated as we are on Comanche land, out here on the Llano Estacado, Coffey’s work in this show anchors it to Indigenous relations to this place and its history. One piece in particular, My First Memory (2000), and its story encapsulates belonging—to place and land, community and kin. Though diminutive in size, it is a centerpiece for the exhibition and one of the first works the viewer encounters: a baby doll body of glazed ceramic, with a room as the torso. Looking into the room from above, there is a group of people sitting in a circle, hands folded in their laps, with kerosene lamps, and a Holy Bible on a side table.

The work represents what Coffey, speaking at the symposium’s keynote address on February 23, described as a “blood memory,” the moment she “came into consciousness” as an eight-month-old baby, in a prayer meeting that took place in her grandfather’s home on the original family allotment. Through the 1887 Dawes Act, allotment dispersed collective landholdings and forced individual ownership of land onto Native families, allowing settlers to buy up the remainder. “The allotments separated us, assimilated us, and Christianized us,” Coffey said. Despite this loss of communal land and culture, Comanche culture persisted, in part through prayer meetings such as the one she experienced as a baby where the performance of Comanche-language hymns and sermons helped preserve language and culture, and the allotments, like Coffey’s, that still remain in the family and do provide a long-standing connection to the land that could otherwise have been lost. The body as a house, as a container for personal and cultural memory, closed in by its four walls yet open to the sky, My First Memory communicates the many layers of belonging, along with its contradictions.

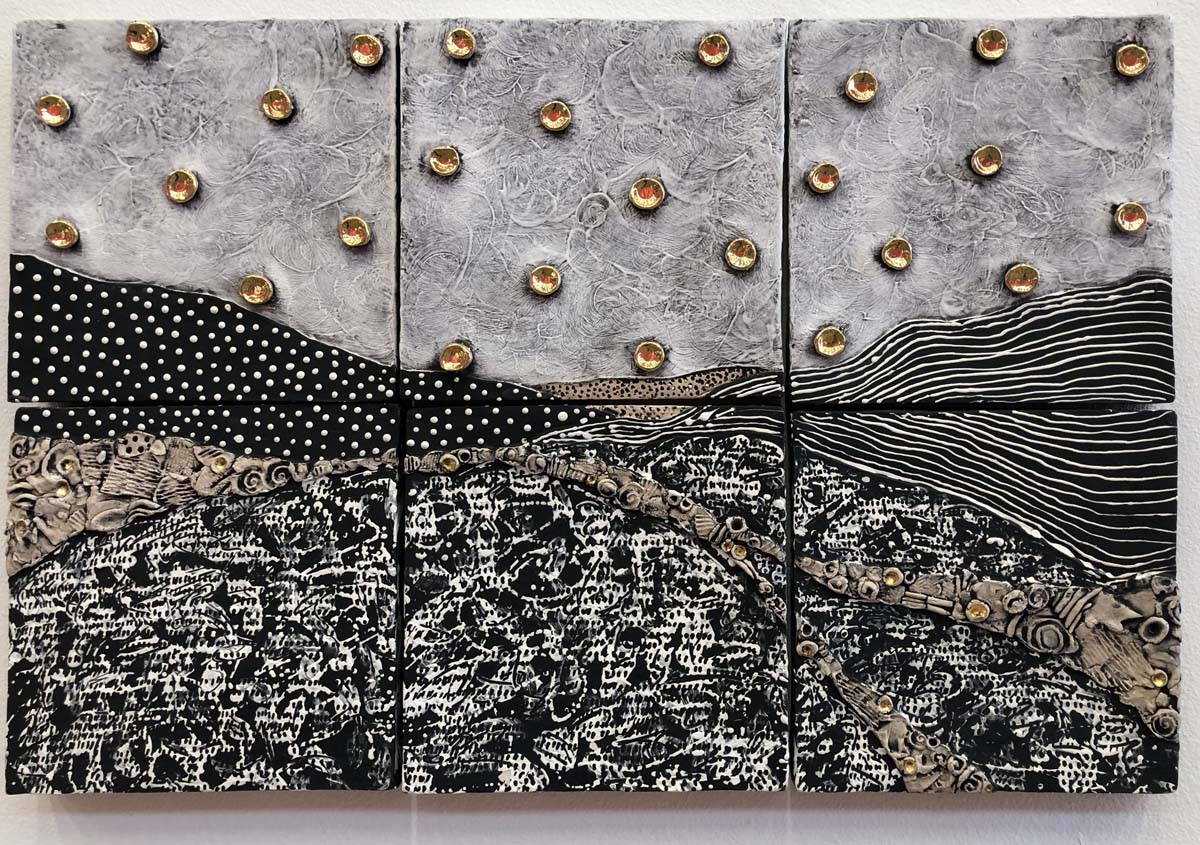

“Clay holds a memory,” Fields reminded us, sharing the stage with Coffey at the symposium’s keynote address. “Clay carries the memory of everything you did to it… very much like humans.” In an artist panel, YellowHorse-Metzger talked of “the clay body,” and working with clay as “connection to the earth mother.” Both artists talked about the land, place, and community as one. “It’s hard to talk about one without the other,” Fields said. They spoke about their connections to the land on the Plains they grew up on and also their ancestral land from which their tribes were displaced. In Fields’s six-paneled wall piece Movement of the Sun II (2011), the landscape is static while the sun appears as a multitude of golden discs across the sky. In YellowHorse-Metzger’s installation Tears of the Sky People (2023-24), hundreds of small fired clay pieces, scattered on the floor and also suspended in the air, hold her tears and the impression of her finger under a blue glaze. Both works mark time and continuity through clay.

Chase Kahwinhut Earles’s (Caddo) practice is focused on faithfully preserving the continuity of ancient and traditional Caddo pottery techniques—from digging his own clay to firing in an open pit—along with the incorporation of contemporary motifs. His work, like Sky People (2023), a disc-like vessel with patterned engravings and figures of a man with a fishing pole and a family taking a selfie with an alien, encompasses elements of past, present, and future all at once. Burgio-Ericson writes that Earles’s works of Indigenous Futurisms are “part of simultaneous temporalities, proposing that as Native people, ‘we exist in all times at the same time.’”

Belonging simultaneously to both past and future, speaking to both ancestors and future generations, these seven artists’ works in clay are rooted in the land while looking to the sky. As a three-fold experience, this exhibition, catalogue, and the symposium show a remarkable dedication to research, attentiveness to place, respect for traditions, and an outlook to futurity, showcasing clay as a medium that continues to evolve and inspire.