Oklahoma-based artist Raven Halfmoon (Caddo) discusses the material and conceptual underpinnings of her large-scale ceramic works.

Raven Halfmoon (Caddo) is known for making monumental clay figures that build on the longstanding tradition of Caddo pottery while drawing on a suite of other influences like fashion, graffiti, or color theory. The result is often embodied in large-scale clay figures, sometimes human, often with many faces, that torque the hierarchical expectations of a stable canon. In the following interview, Halfmoon discusses her relationship to the medium of clay while preparing a major joint exhibition, Flags of our Mothers, which opens this summer at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut, and travels to the Bemis Center for Contemporary Art in Omaha, Nebraska, in 2024.

What is it like packing, shipping, and unpacking your sculptures around the country?

When you start working at this scale and moving these large ceramic works across the country, you have to think about how you are going to build and move the piece before you even start. First you order clay. I went through about 8,000 pounds of clay with my hands. You have to think about the device or pallet that you’re going to build on to hold a sculpture of that size, because once you start building it, you can’t move it. It’s heavy and fragile. Then that thing has to have wheels to slide into a kiln. And then it fires in the kiln for two to three weeks, minimum. Once it comes back out, you have to get tow straps or a company and a crane or a forklift, and then it has to be strapped up, lifted out safely, and either put on a pallet or the bottom of a crate to get shipped across the country. Luckily, once these pieces are fired, they are pretty easy to move around. It’s always nerve-wracking watching my pieces getting uncrated, but I haven’t had any issues yet.

Can you talk about how the Caddo lineage of clay informs your practice?

Clay as a medium was an important part of Caddo traditions for thousands of years, so when I was in school, studying art at the Archeological Survey at the University of Arkansas, holding all these clay pots my ancestors made, I knew that I wanted to continue this tradition of using clay. But I wanted to make things that were contemporary, to make pieces that spoke true to my voice and my experience as a woman, as a Native American living in the 21st century.

Where do you find the clay forms within that nexus of past and present?

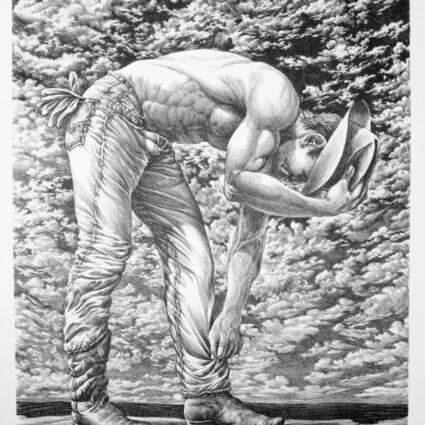

I do a lot of human forms. I do a lot of forms that look like my mother and grandmother. I think that’s where the figure is born. Out of the human experience of what we’ve gone through—not even as a people but me, personally, in my family. I always connect my work back to these two worlds. There’s this world of traditional knowledge and carrying that forward and sharing that history. At the same time, we’re in the 21st century. It’s fast-paced. It’s social media with pop culture, music and Tik Tok reels, and fashion.

I use a lot of Red River iconography—that spiral design that you see on Caddo pottery. Caddo also traditionally had a lot of tattoos, so I’m influenced by tattoo artists. My work ties to color theory as well as contemporary art and classical painters. I’m influenced by graffiti artists and this idea of tagging a work and really placing your work in a moment in time and putting your name on things. I’m the third generation to have my last name, so the element of tagging the work is important as well. My name carries history and culture that I will pass to my children. It’s remembering family and what Native people have been through.

How do material and immaterial parameters of clay and concept meet in the work?

Clay is my most intimate relationship. I’m continuously learning this medium. Not only does it capture fingerprints to an exact tee, it’s tied to time and place. Clay is specific to where it was made on the land. Everything I make, I touch all the pieces. I build them. I’m pushing clay to its max. Because I work with larger kilns making large-scale pieces, I get a lot of breaks in the kiln. I like a lot of those cracks. I want the process to be seen in the work. I want you to feel that human connection, that human experience. They are meant to be emotional.