After living at an abandoned commune in rural Utah for eight years, author Emma Kemp blends history with memoir in her forthcoming book.

Emma Kemp wants to show me Marie’s place.The way she calls her by her first name makes it seem like Marie is an old friend who lives down the road.

But the Marie she’s referring to is Marie Ogden, a soothsayer and religious leader whose Depression-era commune in the desert of southeastern Utah met its end after word got out that members were attempting to reanimate a human corpse with daily milk-and-egg enemas for close to two years.

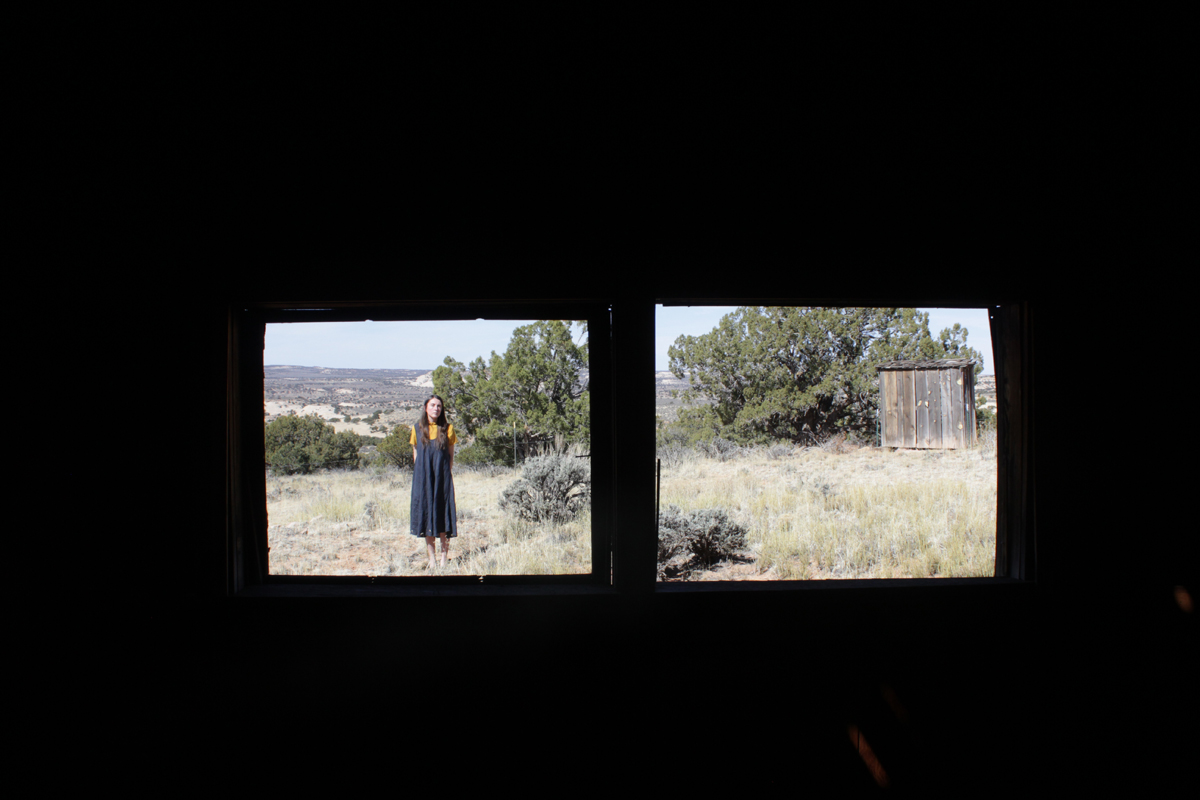

In any case, Emma wants to show me Marie’s place, so we strike off down a narrow path across the property of the former commune, Home of Truth, where Emma Kemp has lived on and off for the past eight years while writing a book about Marie Ogden and her followers. The book, titled Marie’s Place, will be published in 2025.

The landscape lives up to its name, Dry Valley, an unremarkable swath of parched scrubland that pales in comparison to the vibrant red rocks of Indian Creek and Canyonlands National Park just down the road.

“It would be easy to walk around this landscape and these derelict cabins and think this person was a lunatic,” she says. She means Ogden, but all I can think of is Kemp—a Londoner, by the way—spending the better half of a decade staked out in a Utah cabin with no electricity and no cell service investigating, by candlelight, a dead woman’s correspondence with the other side.

We enter Marie’s place, one of the few remaining cabins from the original property that supported about 100 people at its height. The cabin Kemp lives in down the hill has been renovated, but Ogden’s has been left untouched. The windows and most of the walls are long gone.

“I like to come up here and sit when I’m writing,” she says. “I guess I believe in spirits, or at least in the power of your own mind, and so something about coming here, I feel connected.”

Kemp first read about Home of Truth in a footnote more than a decade ago. She can’t remember where exactly, but it was while she was researching other communes established in the desert outside of Los Angeles, where she lives and teaches at Otis College of Art and Design when she’s not being “a total recluse” at the cabin.

“A huge theme in my research and arts practice is women who went rogue from mainstream society,” says Kemp, whose first book, Blue Pool Cecelia, chronicles the tumultuous lives of women in a small town along the Mississippi River. Ogden’s story charmed her immediately.

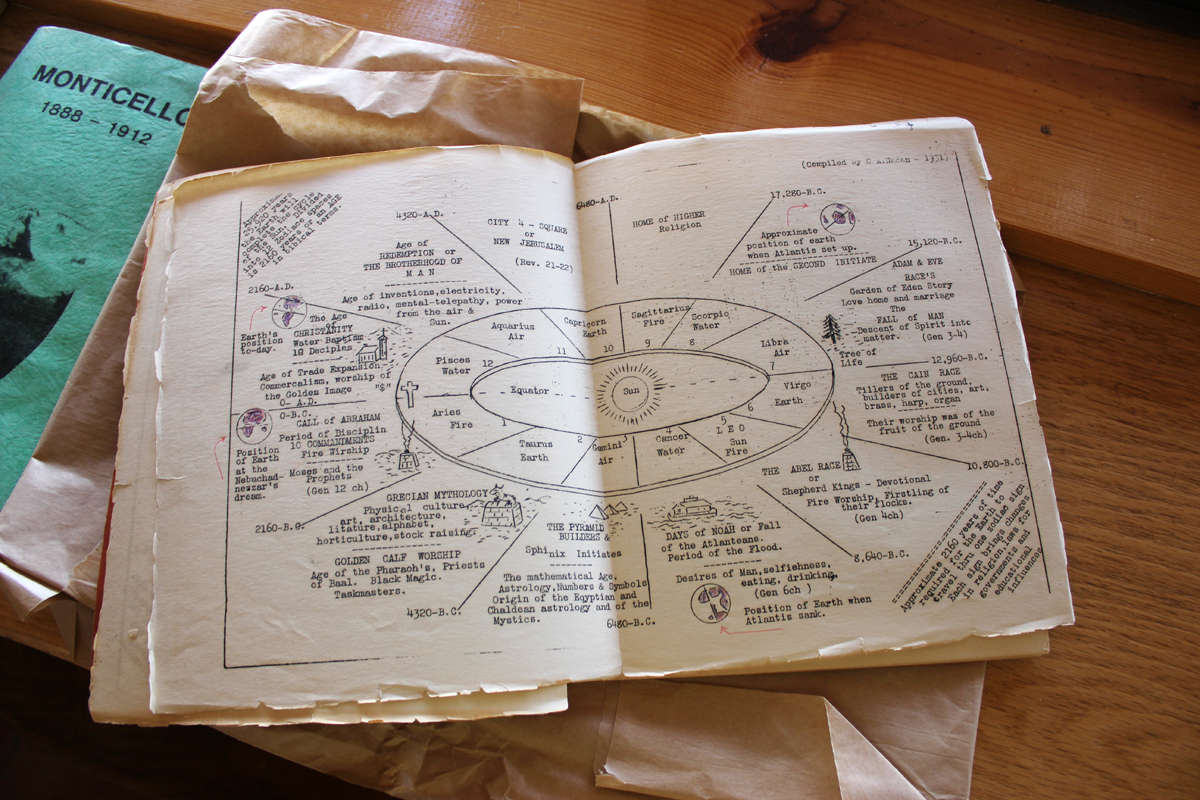

In the early 1930s, following the death of her husband, Ogden quit her life as a New Jersey socialite and began a slow rebrand as a New Age prophet. She became a medium for God’s messages, which were delivered through divine manipulation of her fingertips that would press the keys of her magical keyboard, revealing the word of God one letter at a time.

In 1933, armed with almighty insights and a substantial inheritance, she packed up her Ford coupe and headed west in search of a rock she had seen in a dream. This rock, God advised, would mark the axis of the earth and a special slice of rural America that would be spared from the impending apocalypse. This is where she would establish a community anchored in asceticism, astrology, and numerology. Her followers would abstain from sex, alcohol, tobacco, and meat. They would consult the stars and Christian saints with equal reverence. On her way to Utah, she stopped in the Midwest to recruit people eager to escape the Dust Bowl. For the small price of their entire life savings, she promised them eternity.

When Kemp started writing this book in 2015, there was essentially no trace of Home of Truth anywhere online. “There wasn’t even a Wikipedia page,” she says. And that was part of the appeal. “At first, I thought writing a historical account would be enough.”

Then she met an anthropologist who specializes in mummification. She thought: “I wonder if she could recreate the milk and egg experiment.” The anthropologist could, and she did, on pig cadavers.

That’s when Kemp started to realize that maybe the book was also a memoir, or at least some kind of participatory retelling of history.

“I was learning a lot from the anthropologist about reanimating the flesh using Marie’s techniques, and I realized I wanted to get as close to Marie’s experience as I could,” she says. “I was much more interested in my relationship to Marie.” The book now oscillates between first-person memoir and third-person historical account.

In her practice, Kemp says she prefers to write from within the story rather than from the outside looking in. “Of course, that can be dangerous. Sometimes you get too into it, and you can’t see the bigger picture,” she admits. “But I’d done so much research by that point that it felt right to come out here.”

She followed that feeling one Friday afternoon in 2015 after wrapping up class. She got in her car in Los Angeles and drove more than 700 miles straight through to Utah. “It was a compulsion,” she says. And perhaps something Ogden would have done.

When Ogden first reached Dry Valley, she took one look at Church Rock and knew. No matter that the soil was bad and the aquifer nearly impossible to penetrate, God had spoken through her typewriter: this is where she would build her Home of Truth.

“Or is that revisionist thinking?” Kemp wonders. “Did she really have a vision of this rock formation? Or did she need a reason to choose this place that also happened to be under the Homestead Act?”

The question of revisionist thinking is one Kemp must contend with often, even in primary documents, even in diary entries. She constantly has to wonder: is this actually how it happened?

And for the most part, that’s up to Kemp to decide. There are no other books to reference, no former members left to interview. In fact, the last Home of Truth member to live on the property did Kemp no favors before he died. He burned all of Ogden’s writing from the 1960s and 1970s. “He didn’t want people to think she was a fraud,” Kemp guesses.

Even in her interviews with old-timers from nearby Monticello, Utah, who remember the Home of Truth, she has to consider whether these people are trustworthy narrators of their own memories.

From what she can gather, the majority-Mormon community wasn’t interested in Ogden’s idiosyncratic theology. “But everyone I talk to makes it seem like she was respected, though that could have been different at the time,” she says, acknowledging that perhaps time has enabled a more gracious retelling and at least some mythologizing.

Kemp says she feels a “sense of stewardship for this history” and that the record-keeping process is part of her practice. And with that comes a certain level of anxiety.

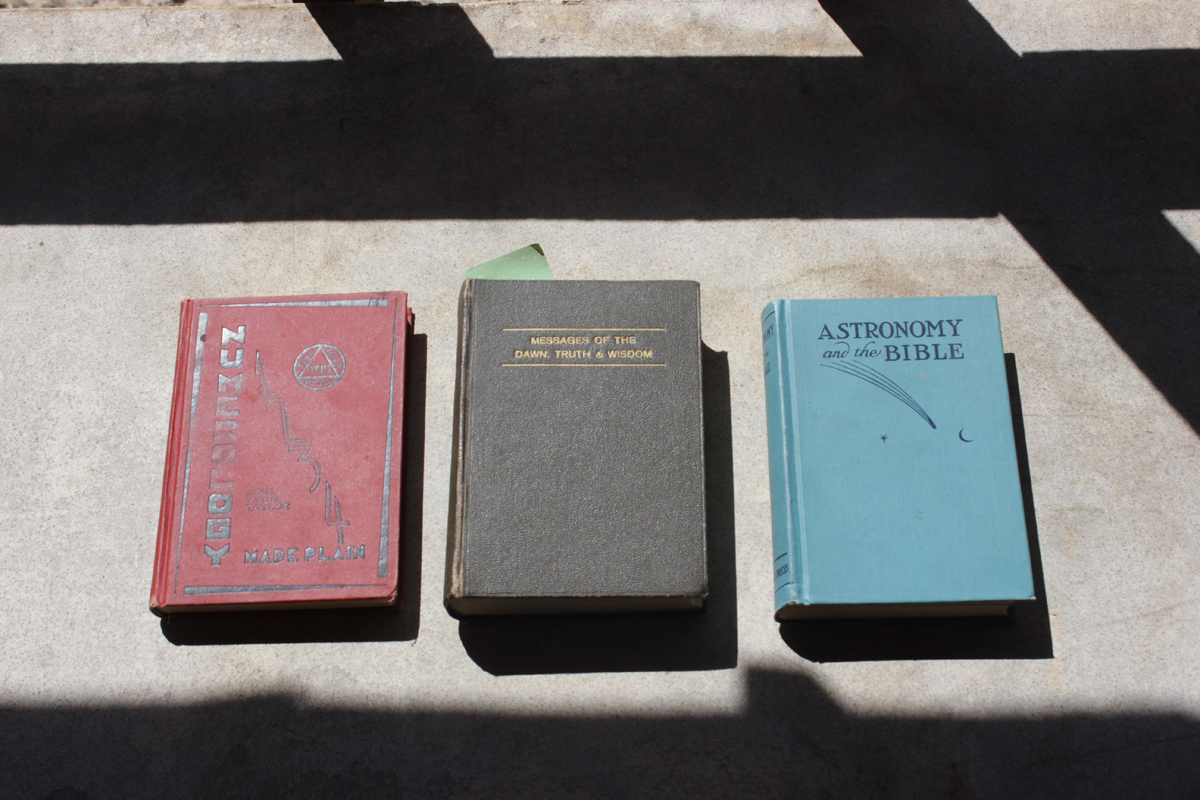

“It’s terrifying because if I don’t find these documents, they’ll disappear,” she says. “I’m surprised I haven’t contracted any rodent diseases. I’ve just been digging around in the cellars of these cabins unearthing mouse-bitten documents of Marie’s writing.”

I’m surprised I haven’t contracted any rodent diseases. I’ve just been digging around in the cellars of these cabins unearthing mouse-bitten documents of Marie’s writing.

Even though much of Ogden’s personal writing from late in her life has been lost, a vast archive of newspaper articles about the Home of Truth has been saved by the San Juan Record, the local newspaper that Ogden purchased and ran from 1934 to 1949.

Ogden used the newspaper to spread her gospel, publishing columns about “Metaphysical Truths” and other updates about the goings-on at Home of Truth. Her public proselytizing went largely ignored by the rest of the sparsely populated region until she introduced a new column titled “Rebirth of a Soul,” in which she described in great detail the process her commune was undergoing to resurrect one of their deceased comrades.

It takes a couple hours of talking with Kemp to reach a point when I feel comfortable enough to ask about the corpse fiasco, and she’s a little exasperated when I finally do. “That’s the one thing everyone wants to know about,” she says.

In 1935, a woman named Edith Peshak needed a miracle. She was fifty-seven years old with a terminal cancer diagnosis, and no medical treatment was going to save her. She needed a spiritual cure, one Ogden said she could provide. Illness, after all, was merely sin manifested, according to Ogden.

But apparently Peshak was beyond absolution. She died less than a month after arriving at Home of Truth. For the first time, Ogden’s promise of life everlasting was put to the test, and it failed.

“I really believe Marie thought she could help Edith,” says Kemp, who sometimes assumes the role of psychoanalyst in order to reconstruct Ogden’s character. “I think she was trying to help Edith in a way that she couldn’t help her husband,” she continues, adding that he also died from cancer.

Either way, Ogden needed to win back her followers, many of whom were already wavering due to the poor farming conditions and general ineptitude of the homesteading crew. She consulted her magical typewriter, which blamed Peshak for not purifying her body and spirit fast enough to overcome the cancer. But God willing, the community could still call her back. All they needed to do, her typewriter said, was feed the body a balanced diet of milk and eggs and await Peshak’s resurrection.

For two years, Home of Truth members tended to Peshak’s body with daily enemas and salt water baths. The corpse mummified in the arid climate, and thanks to its meticulous care, there was nothing particularly “grotesque” about the situation, Kemp says, even if it was morbid.

This made the unusual case hard to prosecute—there was no obvious public health concern. But it was weird, and pressure was mounting from Peshak’s family and law enforcement to bury the body. National newspapers mocked the woo-woo cult, and faith in Ogden’s powers waned. And then one day, Peshak’s body disappeared.

Marie told her followers Peshak had been “spirited away from curious and prying eyes.” One defected Home of Truther testified in an affidavit that he cremated Peshak’s body at Ogden’s behest, though weeks later, a local journalist found what appeared to be the corpse in a cave on the property. Eventually, the state secured an official death certificate and laid the case to rest, at least legally. By that time, many had left the Home of Truth.

“I always wonder what Marie’s legacy would have been if the Edith thing hadn’t happened,” she says. “Because otherwise, Home of Truth wasn’t outrageously freakish.”

But without Peshak, would Home of Truth have been a footnote in whatever text Kemp was reading all those years ago? And would the story of the commune have enough narrative arc to support a book? Would Ogden still capture readers without this morbid demonstration of her flawed and complex character?

“Was she exploiting the vulnerabilities of these Depression-era families? Or was it actually an attractive future for people to try to be part of this experiment?” she says. “Same as now, I think people were hungry for someone to tell them how to live their lives better.”

At least Kemp was when she started researching this book more than a decade ago. “I was drawn here by a crisis of self in the sense of absolutely needing to figure out who I am,” she says. What she found at Home of Truth was a setting different enough and extreme enough to chisel away at the sculpture of her own relief.

“When you’re in a place of contrast, your being is contrasted against that difference,” she says. “It’s easier to see yourself.”

She started deviating from the “autopilot pathway” of her life in Los Angeles and, like Ogden, began in Dry Valley her slow departure from mainstream society.

“It’s still hard to turn away from opportunities in Los Angeles and say: no, actually, I’m going to do this other thing that’s completely bizarre,” she says. “It’s not easy to live here, and I mean on a deeper level than just being inconvenient and not having WiFi. There’s a psychological damage that comes with living here.”

Much of that damage is born from the isolation. But Kemp acknowledges that isolation is also the exact thing she needs to write.

“As a writer, there’s something to be said about emptying your life and connecting with something outside yourself,” she says. “I think that’s what Marie was doing. She wasn’t willing the thought. It was just passing through her. I wish my writing could be like that, but I have to create enough space within me to make that happen.”

As a writer, there’s something to be said about emptying your life and connecting with something outside yourself.

For Kemp, and the many writers and artists who abscond to the desert to work, that internal vacancy is found faster in empty places. Through some kind of osmosis, the contents of oneself are extracted by the vacuum of the landscape, an empty container that pulls forth and dilutes any trace of self.

“I’m rambling,” she says eventually. She’s trying to articulate something ineffable about the patterns of this place, the osmotic force that continues to draw rogue women in. She gives up and begins to light some candles. The sun has set, and it’s dark in her cabin.

“That Marie drew me here, and now you’re here, and we’re having these conversations, and I’m writing this book, and you’re writing this story…” She trails off. “Something about the fact that this place is still drawing people in, that feels significant,” she concludes.