The Wheeler Brothers—Bryan of Lubbock and Jeff of San Antonio—employ maximal methods influenced by humility, music, hidden hot springs, and breakdancing in the Texas Panhandle.

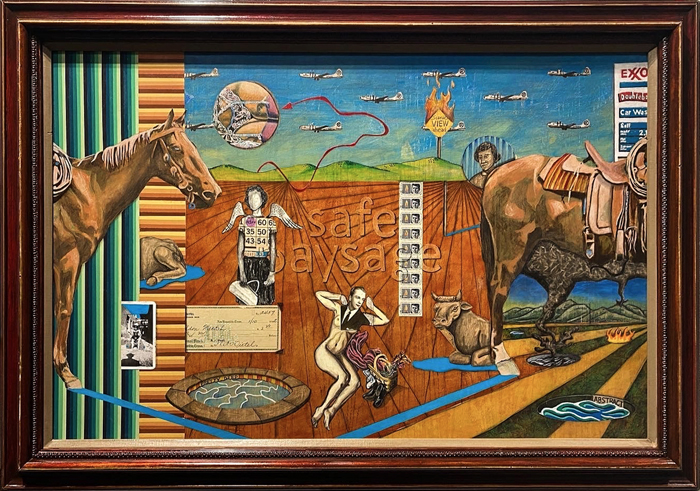

If you hang with Bryan Wheeler for a few hours, the term “maximal” might come up. It’s barbecued into his DNA and also imprinted into the genetic alphabet of his brother Jeff Wheeler. They both tend to populate their work with seemingly random gatherings of images locked together in an internal logic that could be called, say, maximal.

We are likewise gathered, not so randomly, here in Bryan’s Lubbock studio with Jeff, myself, and musician Hayden Pedigo, all of us collaborating on a project for what they call around here the S#%& Show, an annual January event. Now in its seventh year, the show is organized around a single principle: the teams of artists are given a prompt and have twenty-four hours to come up with a piece for the opening the following evening. Hannah Dean and Christina Rees selected the artists this year and supplied them with the prompt “the year 2050.”

Bryan’s studio is in a nondescript metal building in an industrial area on the Brownfield Highway in southwest Lubbock. A few tumbleweeds tangle against a wall of tree limbs next to the alley. Inside, it is organized around art making, music mixing, writing, and preparation for Bryan’s gig at the Texas Tech University art department. Lucky for us, we have plenty of elbow room to work on the S#%& Show, because a lot of Bryan’s work is currently on the road in a two-person traveling show with Jeff. One of Jeff and Bryan’s earliest collaborations hangs haphazardly on a wall above the mixing console.

Billy Collins has poetically pointed out that “trouble” is not Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s middle name, but it can come up in collaboration, especially if you define trouble as being lovingly wooed out of your singularity into a comfort zone that only exists between amiable people.

That is what happened S#%& Show weekend, but I suspect with Jeff and Bryan it is more ongoing, akin to a conversation that pauses, but never really ends. Like shadows extending in different directions from an object illuminated by two light sources, their methods mix, but the origin of each shadow is clear.

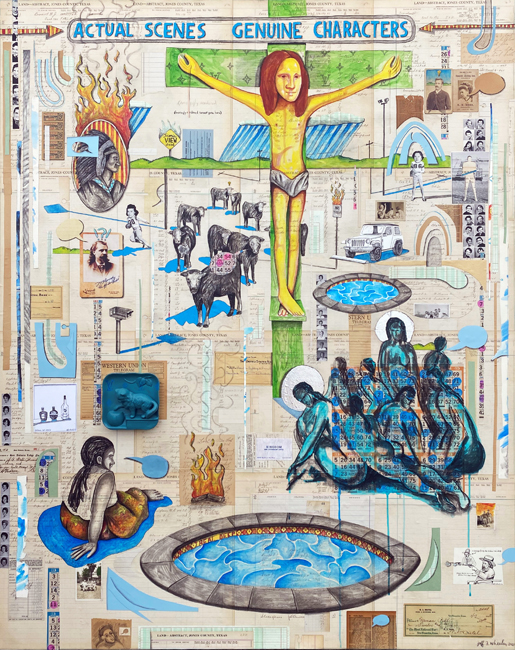

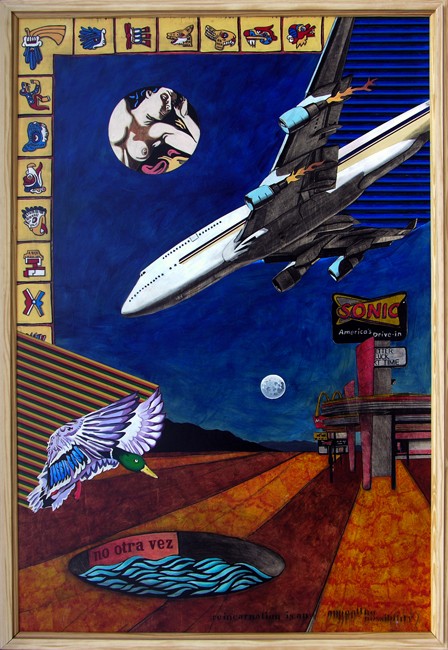

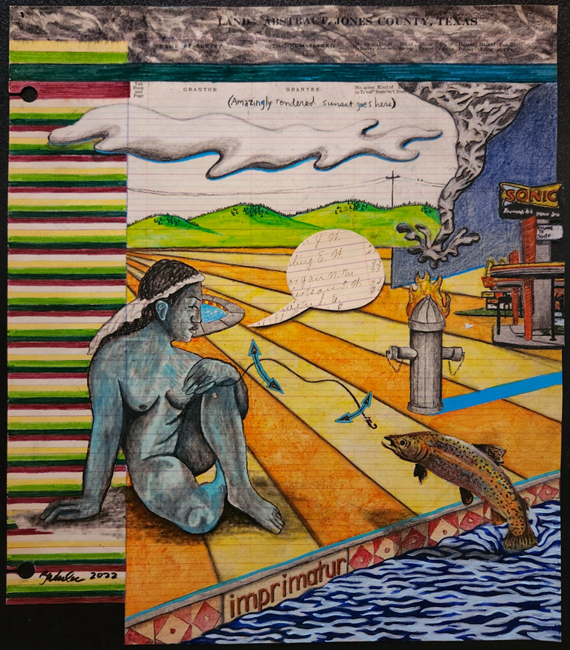

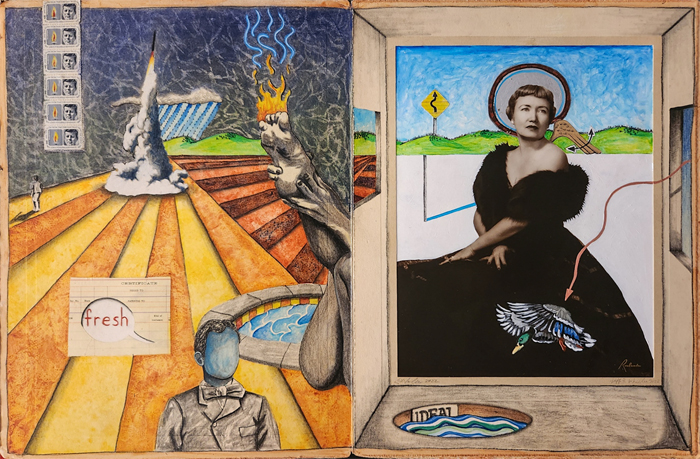

Jeff is fond of the various “insert here” thought bubbles he employs to remind viewers that while he is definitely an explorer of the west, he is no illustrator thereof. The sign may say “insert scenic view here,” but it’s an absence that is created by the endless replication of what might be called Third Millennium Visual Proliferation that is being inserted. Bryan has used the insert phrase, too, but he steps outside the frame, giving it as a playful prompt for the viewer to step in. Either way, absence and emptiness are not the same thing.

Perhaps the conception of the insert-bubble came while gazing at the endless horizon, which plays out unbounded before your gaze wherever you look in the high plains—even in a rear-view mirror, which frames the scene the way the bubble contains the phrase. If you figuratively walk out of Lubbock heading west, eventually the only vertical things within sight will be a grain elevator or a windmill, unless you count yourself. Given this admittedly theatrical description, the insert bubble is a kind of lament.

Both artists reveal spaces that veer from flatness to a cartoonish three-point perspective, sometimes both at the same time in a jocular winking cancellation that leaves a viewer floating in the same nebulous zone that is inhabited by their panoply of golden arches, white-faced Hereford cattle, diving 747s, rainbow trout, skulls, ceiling fans, and hot tubs.

Jeff, who relocated from Lubbock to San Antonio in 2019, has repeatedly traveled the west in search of the next hidden hot springs—and some not so hidden like those that come up in his lexicon of repeating images. The surface of these pools is frequently a Hockney-esque set of squiggly lines in blues, presenting a postcard slick surface that suggests landscape as travelogue, a method that fits well with his commitment to work all the time, wherever he is, with whatever he’s got. You might be making a grocery store stop while heading to Chinati Hot Springs, and before you know it Jeff has made a drawing while using his moves to pass from one aisle to the other.

Bryan’s approach is more literary, but for the times when he goes for a specific text—such as with Slinger, his 2019 homage to poet Ed Dorn—his relationship to storytelling is also a scattered narrative of referents known and unknown. There is no specific order in which his catalogue of images need to be consumed. You, as you sift and sort the information on offer, become the finger post pointing multiple directions at once, finally resorting to the advice given by John Cage: “start anywhere.”

Maybe years of mirroring each other breakdancing in the basements of churches in McAdoo, Afton, Hart, and Hereford north of Lubbock, where their father was a minister, has given them the unspoken method that defines their similarities and their differences.

Bryan, Jeff, and younger brother Tim speak of their grandparents and parents as foundational figures rooted in the Texas Panhandle by humility, community, music, and “fixing things that were broken.”

Bryan is producing an album for Tim, backed by himself and his band Los Sonsabitches. Tim is the primary therapist in the affective needs program at Riverview Elementary School in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, where he works with families and individuals who have suffered trauma. While I’m with Bryan in his studio, he plays a track from the album. Tim’s vocals on the song “Trippin’ Softly” are confidence inspiring and soothing.

The song tells a story that starts like sunrise, greets the day and convivially agrees with itself that hiding with a friend in the tall weeds at a long-ago summer’s end is a moment that still shines vividly even though it is also hopelessly irretrievable. The lyrics are wistful, as if something has been lost, but the trippy tones of the music secure the listener in the present. Because of this anchoring, it can’t accurately be called nostalgia, even more so because the events in the song happened as much in imagination as in memory. Given the tenuous connection that nostalgia has with the present, there is an argument that this is exactly what nostalgia is, a longing for something that never existed.

The work of Jeff and Bryan bears a similar relationship to the nostalgic impulse—that it is reductive, draining images of actual existence. Even though their paintings, sculptures, collages and drawings strike a retro tone and are frequently sourced from archival, vintage, or dated materials, the two artists leave romanticism and longing in favor of an acknowledgement of the absurd.

Bryan’s take on dreaming supports this habit of keeping sentimentality at arm’s-length. Ever since his years living in Montana, rainbow trout have frequently visited him in his dreams, but he doesn’t see painting them as accessing messages leaping from the stream of his unconscious. He paints them simply to honor the place they occupy in his imagination.

A couple weeks after the weekend in Lubbock, I’m back on the road to catch up with Jeff in San Antonio. Jeff’s studio in the South Side Living + Maker Spaces is a jammed collection of objects, materials, all manner of assorted stuff, including numerous found ceramic objects from thrifting adventures, all of which serve as raw materials.

In the midst of the prolifically packed space, the smallest studio I’ve ever known Jeff to work in, a piece caught my eye: Collective Sigh #1, which documents the moment Trump left the White House for the last time as captured by TV news on January 20, 2021. The piece is indicative of another facet of Jeff’s work, of which there are many—historical documentation that comes about the way poems may when you’re doing something else—in the moment as they happen.

“On that day, everything was set aside for the twenty minutes it took me to make the drawing,” Jeff says. “I felt a big weight lift off my soul.”

The South Side building is anchored by Space C7, a large gallery that Jeff is responsible for and where he mounts shows throughout the year. Across the road is the Echo Bridge, where he and artist Justin Parr began a series of COVID-19 era concerts with distancing built in—audience and performer both flank the San Antonio River, but on opposite sides. The concerts, which have included Jad Fair, Erik Sanden with Claire Rousay, Bob Livingston, Longriver, Little Mazarn, and Garrett T. Capps, among many others, are ongoing—with a special event coming up this weekend on February 12.

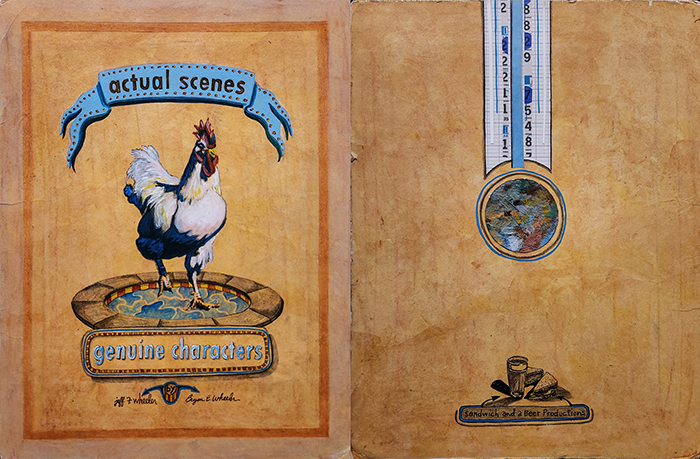

The exhibition Wheeler Brothers: Actual Scenes/Genuine Characters originated at Deborah Colton Gallery in Houston in September 2022 and then traveled to the MAC (formerly McKinney Avenue Contemporary) in Dallas last month. The exhibition will move to the Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts in Lubbock, opening April 7, 2023. Tim Wheeler’s album, Parched, is set for release February 28, with a limited vinyl release May 5.