516 Arts, Albuquerque

August 19 – November 11, 2017

The bees have proven themselves remarkably commodifiable, not only through the products they manufacture that humans enjoy, like honey and beeswax, but also as a pattern, a motif, a caricature. The market loves a stripe found in nature. If panda bears are the symbol of neoliberal consumer capitalist environmentalism, bees are their Etsy counterpart. Their commercial prevalence brings attention to their diminishment in many ecosystems that depend on their services as pollinators, especially for human food production. We rely profoundly on bees. Knowing something of their importance and that their species was under threat, I visited the 516 Arts exhibition, Cross Pollination, in the hopes of understanding bees and other pollinators (butterflies, moths, bats, birds) better.

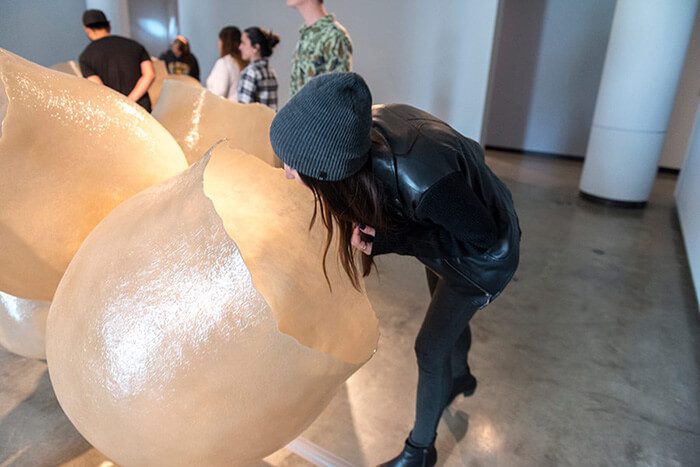

The gallery hummed with insectoid buzzing and some other sound, persistent but pleasant. From three human-sized, amber colored vessels nestled together on the floor emanated a recording of a forty-person chamber choir singing a bee symphony. As I tucked my head inside Jessica Rath and Robert Hoehn’s Resonant Nest, encouraged to do so by the wall text, the singing, the space, its light, and the texture of its echo cradled me. I’m a bee, I thought. I’m home. Several other works in the show offered insight into the dwellings, experiences, and consciousnesses of pollinators. Chinese artist Ren Ri’s videos and photos depict his sculptural interaction with a hive. After dipping his hand in honey and pollen, he placed it into a bee hive overnight and the bees—attacked him? Stung? Died? Left? None of these. They built their hive around him, structuring their honeycomb rooms in the negative space of his hand. “Co-creators,” Ri calls them.

Two huge cocoon-like sculptures hang at the front entrance to the show, each covered with watercolored monarch butterflies by New Mexico artist Stephanie Lerma. The beauty of the pollinator’s body is enmeshed with the architecture of its home, massively enlarged. It is titled Sanctuary. On the two-story wall adjacent, Jennifer Angus’s winged insect bodies form a pattern, like three-dimensional wallpaper, Instagram-ready. I approached the wall, curious if these insect models, too, were watercolored paper. I stepped right back again. They are actual insects. Dead insect bodies, pinned perfectly to the plaster. I peered at the title—A Case of Interruption and Disruption—in horror, and moved on.

On the drive down to Albuquerque, I’d been listening to an episode of the podcast Still Processing in which two black culture critics and a psychologist guest discussed caretaking in the current political climate. They talked about self-care, a much hyped and much maligned term for taking care of oneself, and they considered ways to cope with the everyday trauma of the political moment, in which so many people are under threat every day. They landed on the idea of interconnectedness: how we, humans, each affect and alter one another in ways both positive and negative. How another person’s racism-fueled hatred and anger damages all of us, and how we might begin to listen and understand and sit with the pain of disagreement and rage. At Cross Pollination, I found myself thinking about how we are connected to the bees, but we only seem to pay attention to our effects on a pollinator’s life when that pollinator fails to produce something we need. The bees, and other pollinators, meanwhile, cannot escape human development, destruction, and degradation of their ecosystems. It defines their ability to live at all. And when given a new dwelling—an old piano in Lily Hunter Green’s Bee Composed Live, Ri’s living human hand—this, too, shapes their world.

I was enthralled by Susanna Carlisle and Bruce Hamilton’s videos of bees, especially their virtual reality glasses that allow the viewer to be alone with the bees, to have only the bees and their activities in front of their eyes. A series of close-up photos from the USGS Native Bee Monitoring Program showed the intricacies of a bee’s physical body—they are fuzzy, animated, almost mammalian. They only magnified my shock at the use of collected insect bodies for the front galleries’ “wallpaper.” It is this kind of aestheticization, this turning of a living being into a specimen, that I feel other works in the show strive to work against, to offer another way of understanding vast, small creatures. Insects have a long history: as specimen-objects for the collector, as the raw materials for many artists (carmine, etc). The most important works in this show are the ones that show pollinators as agents, architects, artists in their own right.