New Mexico Artist to Know Now Danielle Shelley updates us on her current work within the political and social landscape, and making art as an act of faith.

This past March (the one that feels approximately 200 years ago) Southwest Contemporary held its second-annual exhibition 12 New Mexico Artists to Know Now. Selected from over 400 submissions, these are the artists we consider to be shaping the landscape of contemporary art in New Mexico.

Just one week after the opening, however, the gallery closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, these artists have continued to create, in terms of art as well as impact in their communities. We’re checking in with each of them to see how they are, and what they’re making now.

Danielle Shelley

lives in Santa Fe, NM

born in Houston, TX

danielleshelley.com | @danielleshelleystudio

How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected your process? Has it changed where, how or when you work? Has it changed the subject matter?

On a day-to-day basis, the pandemic has changed my process very little. In the Before Time, I spent most of every day in my studio stitching, and I’m spending even more time there now. More than nine months ago, I began working on a large piece of political art, so I didn’t have to change my subject matter to respond to COVID-19. What I don’t know is what I’ll do when this year-long project is done.

What are your top concerns for the arts and your fellow artists?

Most artists need their work to be seen, and that’s difficult when COVID-19 is upending the operations of venues from museums to galleries to nonprofit art spaces. The whole arts ecosystem that brought so many of us to Santa Fe is being steamrolled by the health and economic crises. The pandemic has had a catastrophic effect on New Mexico’s tourism industry, which affects many artists and craftspeople who are dependent on local sales. I admire SWAIA and other organizations that are working to help artists sell their work despite the cancellation of in-person events.

How has your relationship with art-making changed during this time?

When I was a child, making art was both a pleasure and a way to get through difficult times in my family. That hasn’t changed just because the difficult times now include the whole globe.

“We make art—we turn to art as a source of the energy we need in good times and bad—because we’re human, and art is one of the essential things we do to be human.”

Tell us about your current projects or pieces:

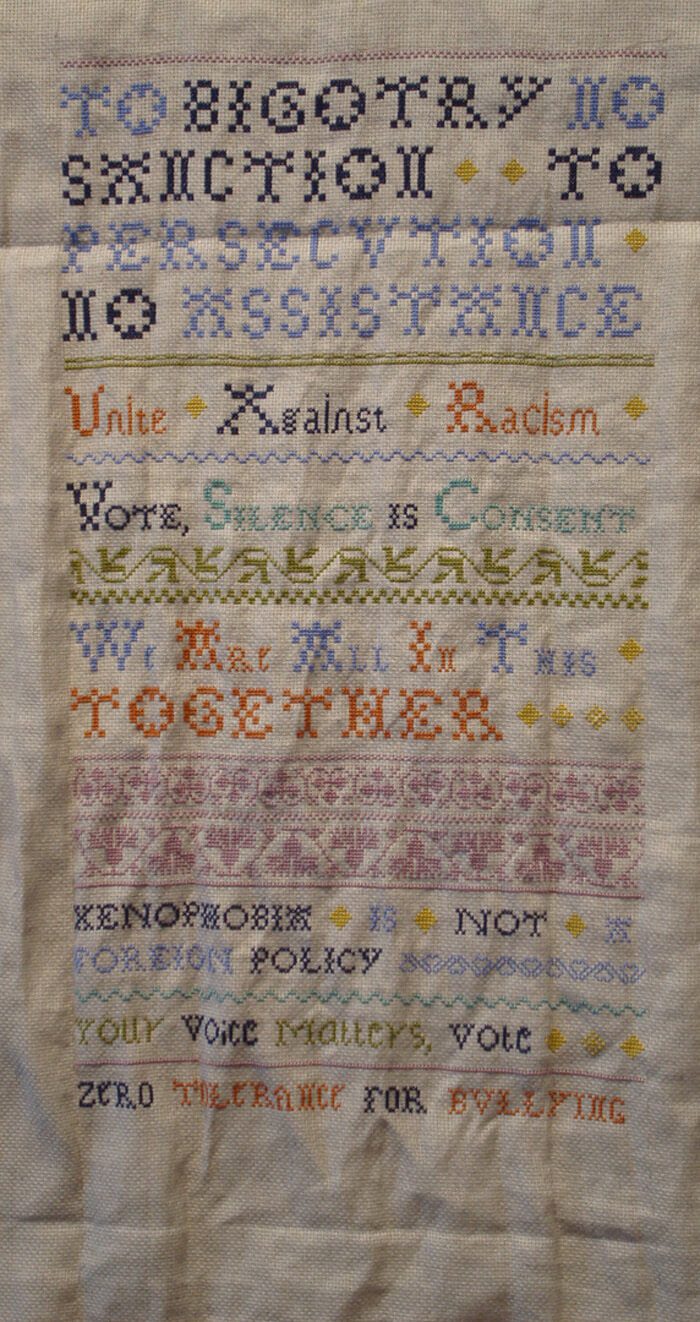

I have been working since November on a very large stitched piece that addresses our current political moment. It is almost six feet square and consists of four embroidered panels. The work combines slogans from contemporary political buttons—one for each letter of the alphabet—with authentic decorative motifs from samplers made by girls and women in America and the British Isles from the mid-1600s to the early nineteenth century. Each panel draws from a different historical sampler style.

The slogans—which start with the Abraham Lincoln quotation, “A house divided against itself cannot stand”—reflect what I believe Americans still share, even in our terribly polarized time. I have been collecting slogans for several years now and thought I had my choices made before COVID-19 arrived, but of course, the pandemic changed some of those choices.

The pandemic has also affected my use of color. I was stitching the second panel of four when COVID-19 hit. Panels one and two are quite colorful, in line with my usual work. But in March, when it came time to start panel three, for the first time in my life I just didn’t feel like using color. So I settled on stitching what I call the Pandemic Panel in two tones of blue. I am currently about half finished with the fourth panel. I guess the initial shock of the pandemic has worn off to some extent because the palette for this last panel uses about half the colors of the pre-pandemic panels. I think of it as a reflection of the twilight times we’re living through.

Is there anything else you’d like to share?

Bad times don’t preclude the making of good art. The Renaissance was a terrible time politically, with ruling families poisoning each other, mercenary armies roaming Italy, and frequent plagues, but it produced some of the greatest art ever made.

As I wrote in an essay in 2009, during an earlier American crisis, “Making art and seeking to create beauty are acts of faith in the future, in the survival of the values of humanism—faith that we will get through the threats facing us, the crumbling of the economic and political world we’ve known, the dying forests and rising seas due to climate change. Art demands recognition that human lives matter, that chaos can be transmuted into beauty and courage… We make art—we turn to art as a source of the energy we need in good times and bad—because we’re human, and art is one of the essential things we do to be human.”