Hung Liu: Catchers

July 19 – August 9, 2019

Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe

On our way to the opening of Hung Liu’s show, Catchers, at Turner Carroll Gallery on Canyon Road, the sky opened up and we ducked into a nearby doorway. “What is this place?” my friend asked, pointing to the nondescript beige adobe which had emerged, Brigadoon-like, to shelter us from the rain. I too had never noticed the rather large front awning between Geronimo and Nüart Gallery on a stretch of road I’ve walked dozens of times. I include this anecdote, because seeing those who are normally obfuscated is central to Liu’s show. The figures in her paintings demand that we look them in the eyes and really see the lives of those cast aside by society.

The artist has adapted the haunting and powerful Dustbowl-era photographs of Dorothea Lange into complex realistic paintings of migrant workers and immigrants displaced by drought and poverty. A world away, but not that far from the detention centers in southern New Mexico and Texas, I could not help thinking about the haunting images of children that have emerged from the horrid conditions in those centers. Liu herself has personal experience with the sort of suffering governments can inflict on children. As a young child, she was sent to a Maoist “re-education” camp in China, and the trauma of that experience has influenced her work and choice of subjects. Matt Pipes, a mixed-media artist who worked extensively on the show as a collaborator and contributed to the gold leafing and resin on several of the paintings, described Liu’s personal connection to the work: “The parallels that Hung draws from being ‘re-educated,’ by being sent out as unpaid labor in rural China, has greatly informed her attraction and sympathy for the subjects of Lange’s photography.” As Liu herself explains, the works themselves are not a direct indictment of the Trump Administration and the U.S. Detention Centers but a wider critique of human suffering brought on by ecological crisis and governmental neglect. As she writes, “I’ve been working on some of these paintings for several years now, so they weren’t intended as direct references to Trump’s concentration camps along the southern border. But as I’ve continued to paint Lange’s refugees, and as the shameful scenes along the U.S.-Mexico border have multiplied, clearly the references between them become obvious. Sometimes art isn’t ‘about’ something so much as near it.”

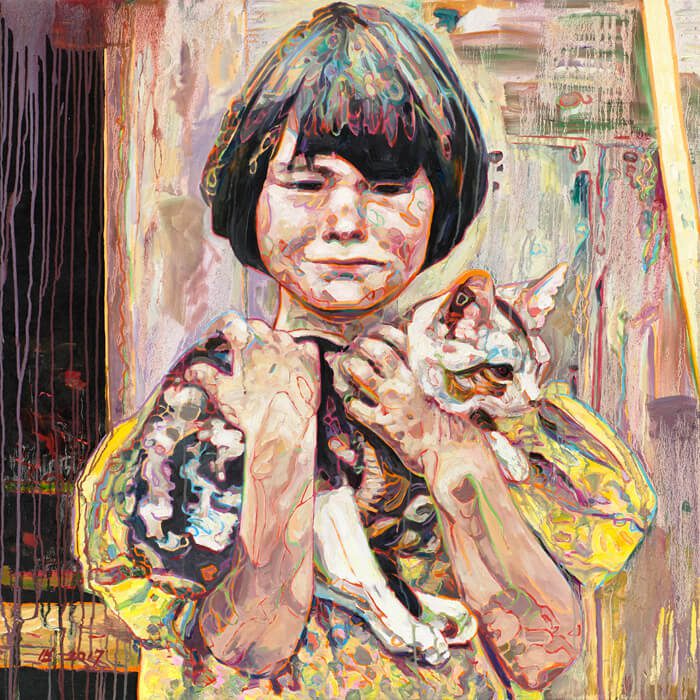

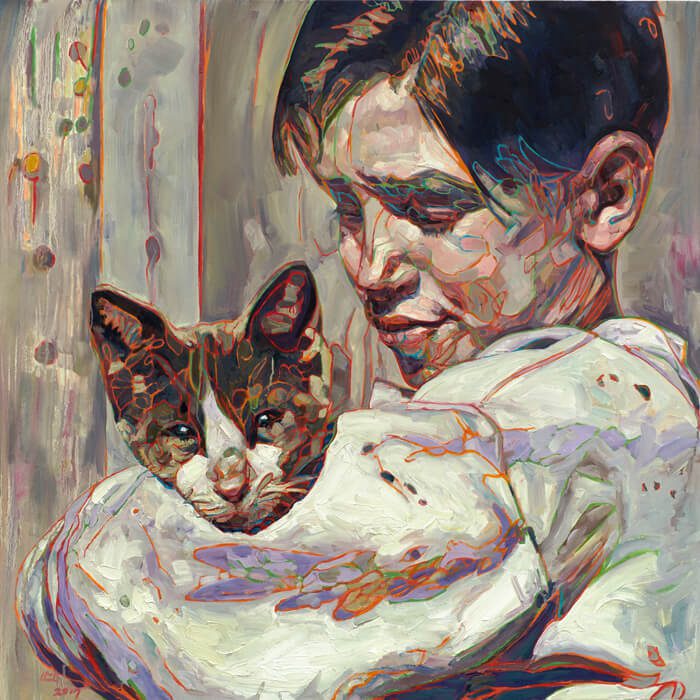

For me, it is impossible to see these works—like one painting of a little girl of about seven, holding her calico cat defiantly and gazing at the viewer—and not think of the children currently being held in detention. The piece is titled Migrant Child: Kitty. She is rendered in Hung’s unique style with swooshes of color and paint dripping down the canvas. Her black hair spills over her forehead, and she gazes at the viewer with an impassive expression on the verge of either tears or of total disaffection, the cat at home in her arms gazing into the distance. These works make children of the past feel present, alive, and contemporary. At the same time, they make us think of the “othering” of migrant children abused by the system. In the face of adversity and poverty, the resilience of children is evidenced in the image of a well-cared-for pet.

Liu’s paintings give an illusion of photorealism from a distance. However, on closer inspection, her mechanics—thick brushstrokes and vibrant colors—become apparent. The paints are chunky and the resin full of depth, while the subjects themselves maintain a highly realistic quality that makes you feel (almost) like you are looking at a photograph. For Liu, her style has evolved as a collaboration between her training and later incorporation of expressionistic techniques. “I was trained in a Chinese Socialist realist style, a very academic and disciplined way of painting. Realism was meant to serve the ideology of the state, so representational technique had to be precise. Mao had to look like a state-sanctioned ideal of Mao, not an expression or an interpretation. The style I have developed in the past thirty years in the U.S. is like a kind of dissolution of the rigidity of Socialist realism. The image softens, drips, runs, and sometimes washes away in the medium. It’s a kind of rebellion against the way I was taught.” Catchers was prepared in collaboration with Trillium Graphics in San Francisco, using a specific technique that they discuss in their press materials: “The resin pieces we make at Trillium are a process that evolved between our master printer, David Salgado, and Hung that [she] calls za zhong, which means bastard or hybrid, because they are a unique hybrid that is both print and painting but is neither a print nor a painting.”

Overall, Catchers helps us see into the past and, through the past, to recognize those we ignore in the present. I left the show feeling more connected to the migrants of the Dustbowl and Great Depression—but also sharing a sense of those who suffer in our own historical moment through displacement and deprivation.