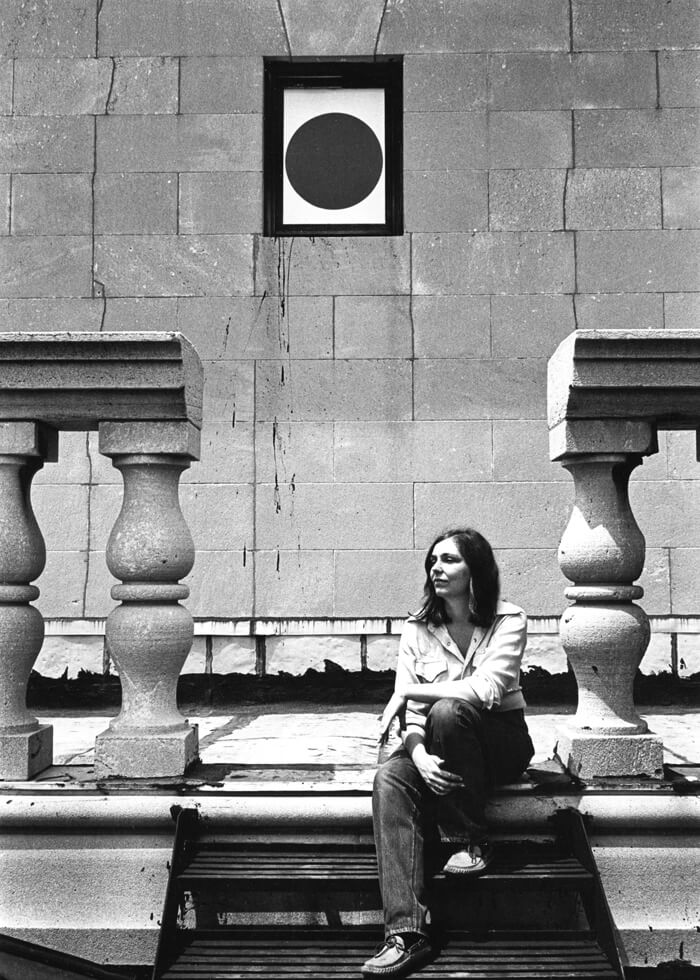

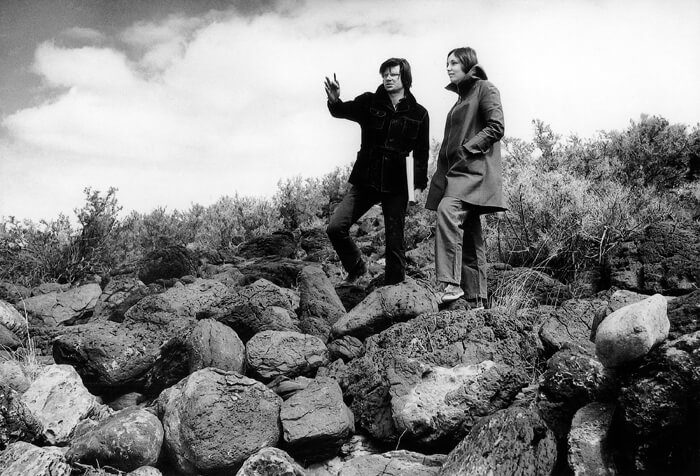

Quietly, a new foundation has come into being in Santa Fe that promises to have a significant impact on art history and art-making, not just in the Southwest, but internationally. The Holt/Smithson Foundation (HSF) was literally willed into existence by artist Nancy Holt—creator of the massive concrete art installation, Sun Tunnels, in the Utah desert— who lived in Santa Fe the last two decades of her life, until her death in 2014. Holt’s estate includes that of her partner, artist Robert Smithson, who is best known for Spiral Jetty, a 1500-foot earthwork of mud, salt, and rock that extends in the Great Salt Lake. Smithson died in an air crash in 1973 at the age of 35 while surveying sites for a piece near Amarillo, Texas. Together, Holt and Smithson were among the pioneers of a genre that has become known as Land Art.

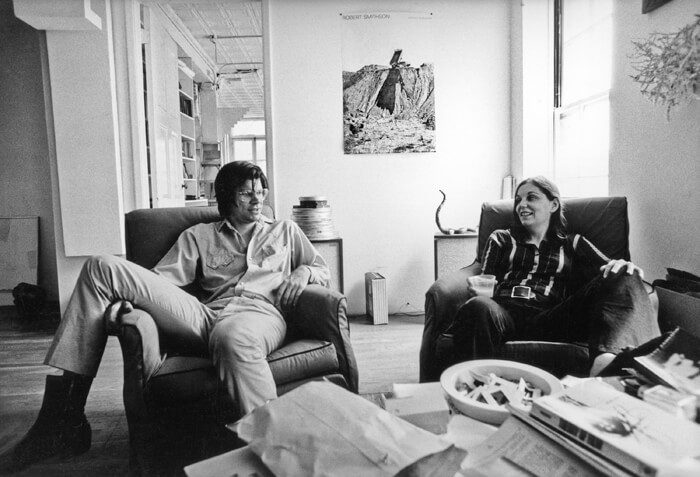

It now falls to the British art historian, educator, and curator Lisa Le Feuvre (pronounced L’Furrv) to realize the potential of the Holt/Smithson Foundation, dedicated to interpreting and extending its eponymous founders’ aesthetic and cultural legacies. At Iconik Coffee on Guadalupe Street in late May, we sat down to talk about her plans for the foundation which, as she puts it, is “built out of the legacy of two artists whose work was generative, research-based, and about asking difficult questions.”

Le Feuvre arrived into the blazing light of New Mexico in February 2018 to begin her tenure as HSF’s inaugural executive director after seven years spent in the gloom of northern England. There she had served as Head of Sculpture Studies at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds. Previously she had been curator of contemporary art at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London, and held posts at the Photographers’ Gallery and Tate Britain. A prolific author on artists of all eras and aesthetics, Le Feuvre serves as a trustee of Bookworks, the London-based artists’ publishing house, and was a 2018 juror for the Tate’s Turner Prize. For someone who, by her own admission, didn’t enter an art gallery until she was twenty years old, her career and wide expertise in art are impressive. Dressed in International Art Black despite the desert heat, Le Feuvre has an impish gap-toothed grin and infectious energy, peppering her speech with “Brilliant!” and other such British-isms. Her enthusiasm makes her approachable—a powerful quality in such an accomplished—and ambitious—cultural leader.

/ / /

By the time Le Feuvre took up her appointment, the board of directors—each of whom was named in Holt’s will—had already established the Holt/Smithson Foundation as a 501(c)(3) non-profit, allowing Le Feuvre to focus on long-range strategy. “Building an organization is rather like building a body,” she explained. “If you have a strong skeleton, you can do anything.”

Already, a crucial structural decision had been made: HSF will have a finite lifespan of just twenty years, terminating in 2038, the centenary year of both artists’ births. “We’d rather put our limited resources into doing things really well over twenty years than over fifty,” Le Feuvre explained. “From a philosophical point of view, the role of the foundation is to get people to talk about these artists. One of the measures of its success will be that it becomes obsolete.” This arc of time allows her to plan its activities in roughly five-year increments.

I don’t think art can change the world, but I think it can change perception. The role of art is to encourage us to ask questions and challenge what we know.

In the first five years, the main tasks are to close Holt’s estate, start inventorying the two artists’ work, and develop digital resources that will become “the hub of all scholarship on Holt and Smithson, and free to access.” Produced in collaboration with New York-based Picture Projects, the fully realized HSF website will eventually present the artists’ works digitally (via photographs showing them in original and current conditions, and in different seasons) and textually, each accompanied by two essays, one by an established scholar and another by an emerging writer. Other HSF activities will include exhibitions, talks, and conferences, an expansive database, artist commissions, and publications—both digital and in print.

“Artists become written into the fabric of art history through exhibitions and publications,” Le Feuvre said. “It’s important to encourage those to be written, so other people can carry on their creative legacy. For example, thinking about the relationship between the human being and nature, about place in terms of siting ideas. Holt and Smithson are relevant for thinking about the idea of the Anthropocene”—a topic she will be writing about in the forthcoming University of Minnesota Press book series Art After Nature. “It strikes me as a really important moment to assess their work in this context,” she said.

In the Foundation’s later phases, it will assemble a ten-person international panel and invite each member to nominate ten artists whose work is deemed to continue (though may not formally resemble) Holt’s and Smithson’s artistic trajectories. From these nominations, up to five artists will be commissioned to create new work on—or relating to—sites in Utah and Maine that were purchased by Holt and Smithson and are now owned by the Foundation.

Considering the foundation’s lifespan, I asked Le Feuvre what kind of art is going to be being made in fifteen years’ time. “It’s impossible to know. And maybe it would be by someone who didn’t train as an artist,” she answered. “Bear in mind that Nancy Holt studied biology, not art, and Robert Smithson was a completely self-taught artist. So it could be anyone. I don’t think art can change the world, but I think it can change perception. The role of art is to encourage us to ask questions and challenge what we know.”

I asked her what else can do that. “Literature. Conversation. Education.” She speaks from personal experience. “I guess it comes from my biography,” she said quietly, her arms folded across her chest as she described the unlikely path she has taken to her current role.

Now in her forties and married to the Colombian artist Oswaldo Maciá, Le Feuvre grew up an only child, in “quite difficult circumstances, in a humble family” on Guernsey, one of the Channel Islands between England and France. Her father was a gardener, her mother a bank clerk. The family moved to Southampton when she was a teenager, and she later journeyed to London to enter the University of Westminster at the precocious age of seventeen. “I finished school early. I wasn’t clever, but I had a very, very good memory. I would read as much as I could. I’ve always been obsessed by libraries—they were the safest, most divine places.” Her youthful ambition was to go into politics and become the first progressive female prime minister. After two years studying psychology and economics, she realized she didn’t have the social class or the trade union connections to succeed in politics and switched to architecture, seeing it as a challenge. “Everyone I knew who studied it looked exhausted,” she laughed.

But for the first time in her education, she was stumped. “I was so incompetent in architecture. I couldn’t build buildings—I have no patience. I was just so messy.” A tutor took her aside and broke it to her she wasn’t cut out to be an architect but did introduce her to the work of artists who focused on questions of spatial experience and built form, like Gordon Matta-Clark, Robert Smithson, and Gego, thus pointing her in the direction of her subsequent career. Just like Holt and Smithson, her own route towards art was meandering.

The day we met, Le Feuvre had recently returned from the Netherlands, where she was looking at Smithson’s 1971 Broken Circle/Spiral Hill in the town of Emmen. In a few days’ time, she was to head to Washington D.C., where a conference was being organized around Holt’s work. A necessary part of creating an “internationally relevant” foundation is extensive travel—Le Feuvre returns to London every few months and heads out to see exhibitions around the world—but not necessarily in the most obvious places. She cites the last Riga Biennial, in Latvia, as a recent favorite.

“Holt and Smithson were established artists who really pushed out of the central international art cities and museums,” says Le Feuvre, arguing that the Foundation’s activities should therefore take place not just in recognized contemporary art hubs but in more unexpected, even remote, locations. For example, next year another exhibition of Holt’s work will be mounted in Lismore, a tiny Irish town comprised of just two streets, an hour from the city of Cork. “In theory, it’s a city, because it has a cathedral,” Le Feuvre chuckled, but Lismore Castle Arts’ exhibition program is “of a quality, curiosity, and difficulty you might find at MoMA. My prediction is that places outside of the traditional art centers—such as New York, London, Paris, LA, Berlin—will become just as important, because they can be places to experiment.”

Talking of out-of-the-way towns with cathedrals, I wondered how Le Feuvre finds Santa Fe’s art and culture scene after nearly eighteen months here. “I think Santa Fe is a really curious place. I can’t articulate why I like it so much. I’m a big-city kind of person. I like working all the time, deciding to go out for dinner at ten o’clock at night. That’s not Santa Fe at all, but it seems like a magnet for people who are interested in the world.”

The world has changed. There’s no denying we are in an ecological crisis. That’s what makes their work even more important than ever before.

I put her on the spot about some of Santa Fe’s artistic beacons. Canyon Road? “That’s the commercial galleries—it’s not art I’m that engaged with, but I still go see everything.” How about Meow Wolf? Is it art? “I think it is culture. I’ve seen great music there, had lots of fun going through fireplaces and bookshelves. It’s not critically engaged art but it is wonderfully entertaining.”

She went on, “I love living here in ways I didn’t expect. But I wish we had one more cultural institution… one that is really a laboratory for ideas, that looks at the uniqueness that I find, as an outsider, of New Mexico in relation to contemporary art… I’d like to see it in relation to—as you now realize, this is one of my obsessions—the understanding of art as an intellectual activity, of raising difficult questions,” she explained. “Smithson was interested in the idea of ‘site/non-site’—what happens when you see a representation of a remote place inside another place. The journey to the artwork is just as important as the artwork itself. These two artists worked in very different ways: Smithson was really all about cognition; Holt was all about perception.”

As someone who has yet to make pilgrimages to their work, and hankers to do so, I wanted to know: what is it like to experience their work in situ? “It’s immersive. It’s immense. And it is intellectual,” Le Feuvre summarized. But what about the form? “The form is really getting you to turn your attention back to what’s around you,” she said. “At Sun Tunnels, Holt encourages us to look much harder at what’s around us. With Spiral Jetty, Smithson is asking: What does it mean to be in one place, and not another? What does it mean to think about how landscape is created—firstly by geological history, then by human history? Today is not the 1960s, ’70s, or ’80s. The world has changed. There’s no denying we are in an ecological crisis. That’s what makes their work even more important than ever before.”