Museum of Spanish Colonial Art, Santa Fe

May, 2018–March 29, 2019

In GenNext, the Museum of Spanish Colonial Art assembles a group of contemporary artists working between traditional genres and contemporary subject matter. Each artist combines the materials and iconography of New Mexico’s traditional Spanish arts from the 1700s forward with popular subjects and imagery that keep this unique category of art vitally relevant. Curator Jana Gottshalk positioned Brandon Maldonado’s work at the opening of the show to set the centuries-spanning tone. His paintings are grounded in the ex-voto tradition, in which the painting acts as a religious offering, a style made popular in the twentieth century by Frida Kahlo.

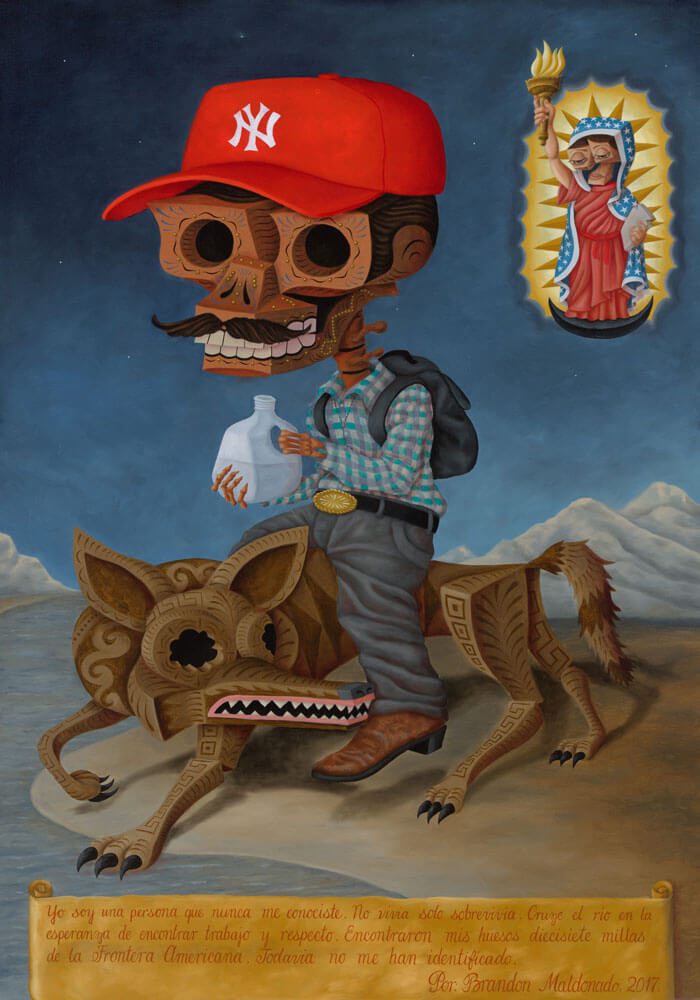

Maldonado’s El Mojado tells the story of an unknown man whose bones were found seventeen miles north of the Mexico/U.S. border. Riding a coyote, carrying only his backpack and bottle of water, somehow it’s obvious that the immigrant is ill-fated. While Maldonado depicts his figures in a boxy, cartoonish manner, the references to art history are clear. The painting is executed in the rich primary palette of the early Italian Baroque era, finished and framed in the manner of Latin America’s Colonial period. A gold band at the bottom of the painting tells the story, in Spanish, of a man who sought a better life, only to suffer and die anonymously in the unforgiving desert. The simple installation piece Border Memorial punctuates the narrative told in El Mojado. Constructed of plastic gallon jugs, which form the shape of a cross, Border Memorial represents the actual life-saving liquid good Samaritans leave out on this side of the border—despite the fact that our government has declared such acts of charity to be illegal. The jugs in Maldonado’s sculpture bear notes written in Sharpie meant to encourage those who cross the desert to survive and to ward off those who might try to sabotage their efforts: “Buena suerte,” “agua pura por su viaje,” and “People are dying of thirst out here. If you slash this, it’s equivalent to murder.”

Gorgeously executed paintings by Patrick McGrath Muñiz bookend the European Baroque sensibility of the first gallery. The usual suspects, including putti, patrons, and martyred saints, merge with pop imagery and provocative references to contemporary experience. McGrath Muñiz’s Revelation looks at first glance like an Annunciation, until you notice that the Madonna floating in the clouds holds a gas-masked Mickey Mouse. Ronald McDonald is there, too, along with a bright yellow happy face where the angel who supports the Virgin would be.

Thomas Vigil’s mixed-media works invoke the imagery of comics, tattoos, and lowriders. His Virgen de los Dolores is spray-painted in layers over stencils on a speed limit sign. Perfectly resolved, it makes me think of driving on Highway 84/285 past Hernandez, New Mexico—the forlorn town made famous by Ansel Adams, today home to a stretch of road that is deadly, mostly due to drunk drivers. You’d better have a Virgen de Guadalupe or a rosary hanging from the rear-view mirror if you want to stay alive on that road.

Three-dimensional works in bulto format occupy one gallery, each made by artistic trailblazers who, beginning in the 1970s, brought Spanish Colonial art into the twentieth century—foremost among them Luís Tapia and Marie Romero Cash. Several works by Tapia inhabit a corner of the room, informing the viewer that contemporary Spanish art began a half century ago when the artist took a chance and stepped away from the old, faded tones that had come to be accepted as historically accurate. Tapia’s research led him to use saturated colors combined with exceptional carving skills and a dry sense of humor. GenNext proves that New Mexico’s artmakers understand their unique place in history.