Peter Sellars’s new staging of Doctor Atomic refuses to allow the audience to look past the Pueblos, look past the people, look past the land affected by nuclear weapons. Instead, it foregrounds them. Rather than an opening chord from the orchestra, the opera begins with a drumbeat and rattles of Pueblo singing. The bare stage fills with Pueblo dancers. This collective of dancers, ranging from elders to children, came together from Tesuque, San Ildefonso, and Santa Clara Pueblos, whose land the Opera and Los Alamos National Laboratory occupy. They performed a Corn Dance, one of the important traditional Pueblo dances of summer, and as the seat-back subtitle screen informed us, this was part of the opera. Something new, significant, and unprecedented was afoot.

The Pueblo dancers open the show with prayer and blessings, and worked closely with choreographer Emily Johnson to weave elements of the Corn Dance throughout the second act, during the moments when the Trinity test is imminent. Visually, while the metal sphere glows and the principal singers fret over what is to come, we see Pueblo dancers of all ages surrounding them. They enter the stage from the physical direction of their Pueblos, moving among and between the singers. Their constant presence on stage with the scientists collapses the decades between the historical figures of 1945 and the Pueblo residents who’ve occupied this land for hundreds of years. Several Downwinders, who suffer from the effects of the tests, stand on stage, demanding their presence be acknowledged. The effects of the Manhattan Project suddenly seemed anything but historical.

Wanting to understand how this collaboration took shape, I spoke to Mina Harvier, a member of Santa Clara Pueblo and a coordinator for the Pueblo Opera Program, which brings Pueblo youth to dress rehearsals at SFO. She was brought in early as a consultant on staging something new. “We heard Peter wanted to bring [Doctor Atomic] to New Mexico, and he wanted to hear from Native participants,” Harvier recalls, “so the Pueblo Opera advisory committee members went to LA to meet with Peter about what he envisioned and how we could help him. But the biggest thing was that no one ever said, ‘We think you should do this.’ They said, ‘You guys are the experts. You call the shots.’ It was us having our presence felt, our voices heard.”

Harvier’s husband, Jordan, a singer and drummer in the show, echoes this sentiment. “Etiquette is key, and Emily and Peter did it right.”

Johnson, a choreographer of body-based work and a Native Alaskan of Yup’ik descent, came to this project with a process-driven openness. “I don’t choreograph leaps and turns. I didn’t want to choreograph segments. I want to be able to look at the whole. I think of dance and choreography in terms of energy, and of exchange.”

That way of working meant bringing no pre-conceived ideas into rehearsals, with nothing choreographed before she arrived in Santa Fe. “I have a long practice of connecting to land,” Johnson told me, “and connecting with people of the place I am in. And as a touring artist, that’s really important for me to feel like I’m doing something of any vital import.” Johnson began by listening. “We held talking circles with Downwinders, conversations with people who used to work at the lab, people from local Pueblos, people who live here… And those circles became healing circles. A psychiatrist who used to work at the lab met someone on their third bout of thyroid cancer, and they were able, across the circle, to say there is no animosity here and ask: ‘What do we do, moving forward?’”

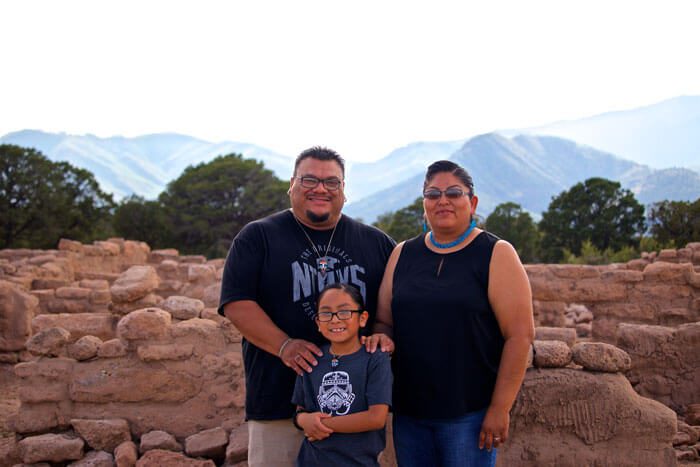

The results of the collaboration, born from hearing and respecting what was said and what was offered, inspired Johnson. “We brought the Downwinders to perform with us. And the performers from Santa Clara and San Ildefonso and Tesuque. I had no idea it would generate into a Corn Dance being shared! I had no idea Santa Clara would write a new song! I had no idea in the second act we would develop a new pathway for that dance so that it is alive within the opera in a completely new way. We just had to be open.” Thus Johnson’s choreography was informed and infused with the contributions of Renee Roybal, Claudene Martinez, Erik Fender, and Leon Royal from San Ildefonso; Reyes Herrera and Daniel Hena from Tesuque; Lyle Lomayma and Mina and Jordan Harvier from Santa Clara.

No one I spoke to ever heard of such a thing happening in opera. As Jordan Harvier said, “This is the rarest opera you’ll ever see, and because of that, it’s sacred in its own way.”

At a panel held in Santa Fe for the Society for Applied Anthropology, Tony Chavarria, Curator of Ethnology at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, said that one way to de-colonize museums is to infect them with Indigenous knowledge, to “Indigefect” them. Indigenous knowledge, perspective, and presence, unlike other infections, don’t harm, but heal. This is what has happened at the Santa Fe Opera. Doctor Atomic was Indigefected by the perspectives and presence of Native people, former victims, now leaders who invite the audience to see them, to see their land, their histories, and their presence as a blessing for all.

During a summer that saw the first Indigenous participation in the Santa Fe Opera and the end of the Entrada pageant, we might consider the historic rains and flooding of Santa Fe not as destruction, but as a cleansing of past violence, in order to move forward in a more human and creative way.