“Let me be the conduit:” Jeffrey Wentworth Stevens, a Denver-based jack of most trades and label boss of Multidim Records, talks cassette releases and trading a Snickers for flyer design.

How many masks wear we, and undermasks,

Upon our countenance of soul

—Fernando Pessoa

Like Pessoa, Jeffrey Wentworth Stevens trucks in heteronyms.

He’s the musician, inventor, designer, artist, photographer, videographer, historian, and creator behind the electronic music entities Andre Cactus, George & Caplin, Morriconez, and AMBIT. He is half—the ethereal psychonaut half—of Wentworth Kersey’s “bootgaze” compositions. (The other half is songwriter Joe Sampson.)

He has composed a sound installation for the Denver International Airport, written soundtracks for films and ballets—most recently, the documentary film Hanna Ranch—and is a tireless, inspired promoter of Colorado electronic musicians and artists through his label Multidim Records. He is also a father and an elementary school teacher who started an after-school skate club earlier this year.

A Denver native, Stevens is in constant awe of artists working at the intersection of sound, music, and technology—and he endeavors to support them, guided by a spirit of community and collaboration.

I sat down with him while our kids played with Legos to talk about his work, what drives him, and how the 1990s Denver DIY scene continues shaping him. His studio is a closet in his Denver home. Really. A desk holds his keyboard, mixer, several effects pedals, cords feed into and out of all sorts of recording equipment, and around it all hang pants, dresses, and shirts. You can see a speaker on the floor peeking out from the winter coats.

“[In Denver in the 90s], there were always people who were kind of going to bat for us,” says Stevens about the city a few decades back, “so it’s great to do that and build that community again but through a different lens.”

Stevens explains that Rick Griffith—the incredible graphic designer, activist, and, with Debra Johnson, proprietor of Denver’s Matter bookstore—basically adopted his first band.

“He said, ‘You just pay me a Snickers and I will make all your flyers.’ And that helped propel me. Those little moves kept me going so I could do bigger and better things,” says Stevens. “There were people there who were just kind of advocating.”

Stevens’s Multidim Records holds this type of supportive propulsive advocacy at its core. Later this month, the label is putting out artist and musician FLYVEE’s debut album.

“She literally didn’t even have speakers. So we got her speakers and a sound card for her computer… to me that’s what keeps people doing it,” says Stevens. “Pushing people who are working at the fringe, you know.”

“It’s not people who are trying to make big money or sell out concert halls,” he continues. “They’re experimenting with sounds, it’s all their vision, and there’s no compromise. That feels really wonderful. Let me be like the conduit. Let me set the table for you so you can lay out your meal, you know?”

Stevens himself creates comprehensive personas—my friend Juliette reminded me of the saying “soup to nuts” the other day, which is hilarious, weird, and applicable here—for his own electronic music projects complete with origin stories, artistic influences, and other details.

Meanwhile, Multidim is a collaboration. The label started in 2018 with him and his pals Tommy Metz and Michael King. Stevens now oversees the label on his own but enlists help from friends, musicians, artists, and his family. Each album release comes in two modes: a limited-edition cassette tape in a one-of-a-kind case, and a sound file available for streaming and downloading.

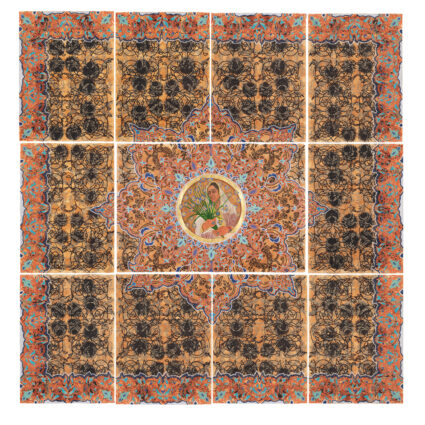

FLYVEE will stitch cassette holders for each of her cassettes. Denver artist Zach Reini designed covers for two releases using a programmed robotic arm to ink each cover. H Lite and his mother embroidered the case covers that accompanied the H Lite album A.V. Tone Alterations. Andre Cactus’s release Dune Juice features a basketball court hand-drawn in chalk on each tape.

“In this age of music, where you can stream anything, I want things to be tangible,” Stevens explains. “I want to feel the human effect. When you hold it in your hand, there’s this humanness to it. Music is so sacred to me. Then there’s this you-had-to-be-there kind of feeling. It makes it special that way temporarily.”

On July 24, 2021, Multidim hosted a Listening Lawn at Carpio Sanguinette Park, which is built on the remains of an abandoned sewage treatment plant in Denver’s Globeville neighborhood. In 2017, Globeville was one of the most polluted neighborhoods in the country and one of the poorest in Denver, according to The Denver Post. Today, the residents have seen the Interstate 70 expansion raze their homes and the enormous National Western Center development threaten more of them.

To that point, DIY culture, to me, trusts humanity in a way that capitalism explicitly does not—it admires and embraces serendipity, works hard as hell, and makes deliberate decisions informed by the struggle of the worker, the have-nots, women, people of color, the wrecked environment, and the outsider. All of this courses through Stevens’s decades-long artistic life.

The Listening Lawn event went well. Some attendees set up an impromptu four-square court. It was an all-ages show, featuring both experienced performers and new ones like FLYVEE. Speakers and turntables were set up on tables and people sat in the grass. Basically, everything you need for a great show, nothing superfluous.

“It was really cool,” says Stevens. “A couple people like Ryan [McRyhew, the musician behind Entrancer], who’s been in the DIY scene for a long time, he’s like, ‘That was the first show in a long time that just felt like it was a celebration versus coping with a loss of an artist or coping with the loss of a DIY space or coping with what’s going on around us.’ It felt amazing for me to hear that.”