February 10, 2017

form & concept, Santa Fe

The Women’s International Study Center (WISC) and form + concept gallery collaborated to present a lecture by Chad Alligood, curator at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art (yes, Alice Walton’s museum in Bentonville, Arkansas, which has turned out to be quite a remarkable institution). Thanks to WISC’s fellowship program, Alligood was able do a residency in Santa Fe while he studied the early (and under-researched) minimalist works of Judy Chicago. On February 10, Alligood gave a presentation on his discoveries to a capacity crowd at the gallery.

According to their website, WISC “advances the work and study of women in the arts, sciences, cultural preservation, and business and philanthropy…” It does this through its Fellows-in-Residence program at the Acequia Madre house in buildings adjacent to the main house, a 5,400 square-foot edifice completed in 1926 by, fittingly, three generations of accomplished Santa Fe women whom poet Charles Fletcher Lummis called the “three wise women”: Eva Scott Fenyes, her daughter Leonora S. M. Curtin, and granddaughter Leonora F. Curtin, also known by her married name, Mrs. Yrjo Paloheimo.

Alligood’s presentation represents the first in a series of investigations on Chicago’s career—which will be compiled into a monograph that will feature thirteen writers who explore a different era or aspect of the artist’s career. Alligood’s is to be the introductory essay. The monograph will be published and distributed by the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C.

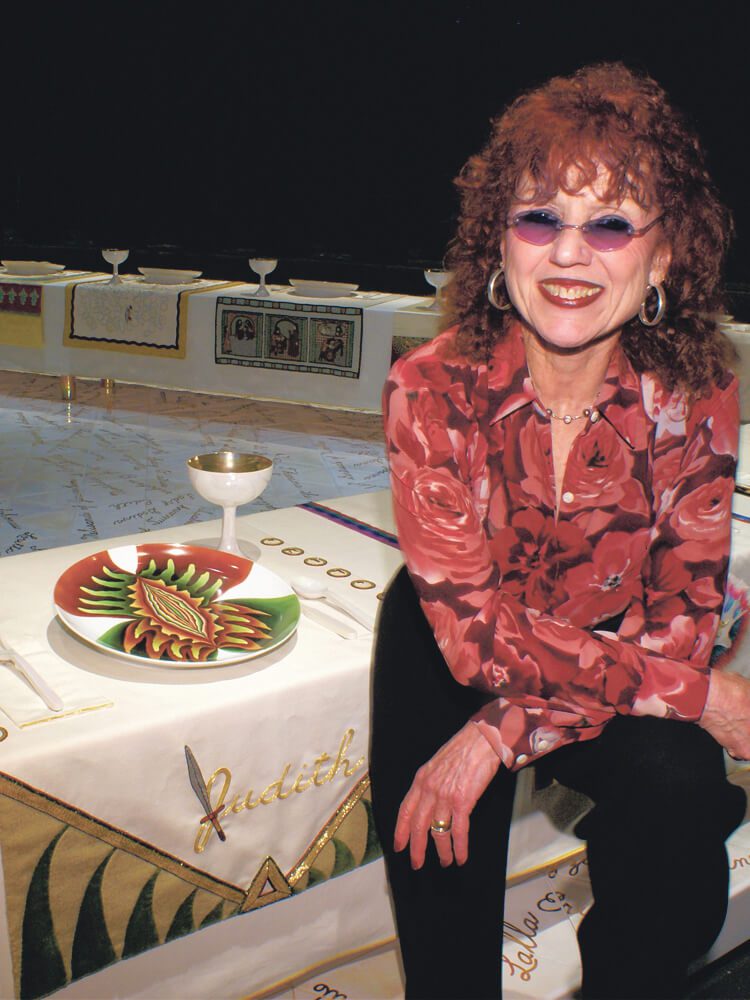

Of course, Judy Chicago’s is an iconic name in the rapidly shifting art history of the second half of the twentieth century, as it moved from the rowdy machismo of the New York School to Donald Judd and company’s coolly masculine Minimalism. Chicago’s Dinner Party (1974-1979) now takes pride of place in its permanent home in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, where it has been since 2007. The artwork tells the story of, as Chicago likes to put it, the women who cook and clean up after Thanksgiving dinner—women whose names were nearly lost to history until she and her fellow researchers found them in libraries and other documents. Remember, if you will, that before the 1980s, art-history textbooks did not include women artists in them. As Chicago recalls, women simply weren’t accepted as artists; she was the exception that proved the rule.

The artwork tells the story of, as Chicago likes to put it, the women who cook and clean up after Thanksgiving dinner—women whose names were nearly lost to history until she and her fellow researchers found them in libraries and other documents.

Before making the celebrated Dinner Party, however, Chicago worked as a Minimalist of sorts. The movement, noted Alligood, was “an art of negation” “seen through the eyes of a man,” minus any personal expression, especially as formulated by Donald Judd in the early ’60s. In amusing succession, Alligood showed images of Carl André’s Lever, likening it to the “male organ” except that it was presented on the floor. From Judd’s stacks to the phallic shapes of other Minimalists, says Alligood, their art was reduced to “a long extension meant to be handled.” Dan Flavin’s neon installations were positioned in a line that was “a diagonal of personal ecstasy.” Need we go on?

Chicago moved through the testosterone jungle that was the art world in the mid-twentieth century by incorporating into her work her own biomorphic and ephemeral forms. Her Minimalism lost credibility with the men when she infused it with color—“sensate, physical, and emotive,” she says—as opposed to the monotones of male Minimalism. The pastels of her Rainbow Pickett must have truly alarmed her male cohorts; it remains one of my favorite pieces by Chicago. (Originally made in 1965, the artist destroyed it to deflect storage costs; it was reconstructed in 2004 for an exhibition, A Minimal Future? Art as Object, 1958-1968, at the Los Angeles MoCA.) I was lucky enough to have encountered a version of this show at LewAllen Contemporary in Santa Fe in 2004, a show I continue to find meaningful. By the end of the ’60s, according to the artist, she was “tired of being a man in drag” and began exploring forms that could be considered feminine in essence, including her “donut” and “cunt” forms. The Dinner Party would soon follow, and history was made.