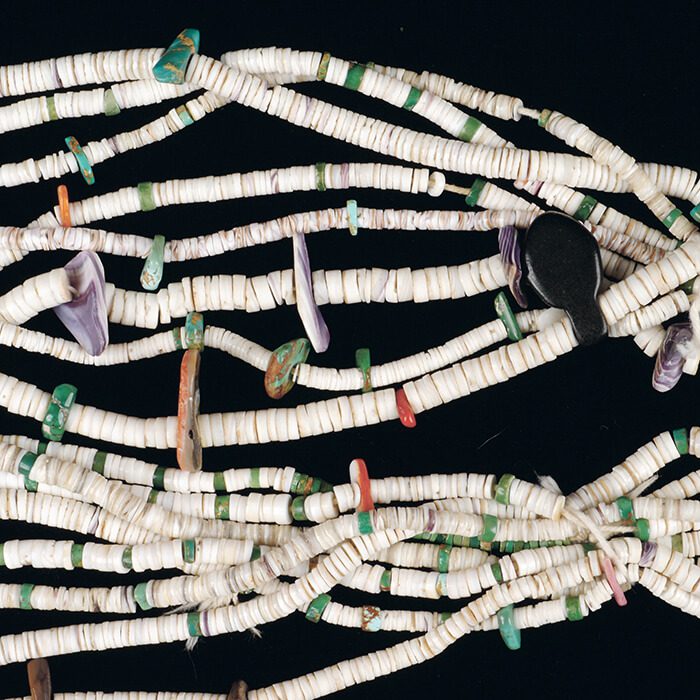

SHELL, TURQUOISE, AND JET NECKLACE

Description: Made and modified, 1890-1935. Pueblo-made shell and turquoise beads; turquoise jet and shell tabs.

Provenance: Hastiin Klah

Accession date: Gift of Mary Cabot Wheelwright, October 1, 1938-1939

Category: Navajo ceremonial material

Institution: Museum of Navajo Ceremonial Art (Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, Santa Fe)

If an object you hold dear could speak, what would it say? Would it talk about the circumstances of its making, who it came into contact with, or where it’s traveled? You see, objects are born into the world, moving about from place to place. Sometimes they are passed on through generations or used up until, at some point, they reach obsolescence and get discarded. Another class of objects ends up in museum archives where they are destined to become artifacts, losing one kind of value and attaining another. This series is about piecing together the material histories of objects. It is also about reckoning with their lives while recollecting how they ended up in our most celebrated regional museums. Each story will be about a single object from a single institution.

–

In between the small, circular white shell and turquoise beads and amongst the slightly larger hunks of jet are purple accents, small mysteries that tell of the Atlantic Ocean. The color is somewhere between lavender and amethyst, rich from minerals in the sea, yet curious in a multistrand necklace of Southwestern design. Oddly shaped beads carved from the marbled inner shell of the quahog clam circulated far from the arid territory of Dinetah where Hastiin Klah, its keeper, lived.

Typically, quahog or hard clams are found along the coves and sounds of the Atlantic Ocean. Eastern Woodlands tribes hewed the shells with quartz tools into tubular forms and then strung them onto long cords like Chinese money. The strands, or wampum, fulfilled multiple roles as ceremonial gifts and, when Europeans arrived, forms of currency. The Onondaga people, one of the five tribes of the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) League, also held that wampum were living records. The most well known is the Two Row Wampum, which marks a 1613 agreement between the Iroquois and the Dutch government.

At some point—no one knows quite when—Klah gifted the necklace to Mary Cabot Wheelwright with its quahog tabs (a shape quite unlike the tubular bead forms that were common) from a body of water far beyond. As the story goes, the two met in 1923 at a Mountain Chant in Chaco Canyon. Wheelwright, like many moneyed East Coast Anglo women at the time, took an interest in the Southwest. She was one of several to become an amateur ethnographer, driven by the impulse to record Diné (Navajo) culture in response to forceful government assimilation on and off reservations. Her obsession with preservation resulted in the founding of the Museum of Navajo Ceremonial Art with Klah in 1937, later to become the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian. Klah was a Two-Spirit person or Nádleehí from Bear Mountain, near Fort Wingate, New Mexico. As a celebrated gender-fluid being, Klah could hold roles in his community generally attributed to both men and women. He was a practiced Hataalii, or ceremonial medicine man, and a weaver who broke with tradition when he began memorializing ephemeral sand painting designs in massive textiles.

Klah was also preoccupied with the sea. In the late 1920s, he and his apprentice/nephew Clyde Beall Begay traveled to Santa Barbara, California, with Wheelwright. In 1931, they traveled with Wheelwright again, journeying eastward to Maine by way of Wisconsin. Along the way, Wheelwright recalled that Klah and Begay were “classed as colored” and denied dining and accommodations.

They arrived on Maine’s northeast harbor where Klah and Begay drifted in boats and walked along a shore encircled by tall spruce trees. On his visit, Klah went to a Japanese Tea ceremony, created a sand painting on the terrace of Wheelwright’s house, and collected sand around the harbor, as well as Cape Cod, for himself. In a recorded interview, Wheelwright, in unmistakable East Coast drawl, recalled, “One day he asked for a glass fruit jar, and wading knee deep into the water, he stooped and filled it with sand, pebbles, and crushed shell that was under the water.” It may have been that, dressed in his velveteen shirt and cotton trousers and wearing a silver necklace and belt, Klah collected the purple shells while wading into the water that day. It remains an open question. Shells in the Southwest were not uncommon, for Diné and other Indigenous trade networks were vast, and shells from the Pacific coast or Central America were exchanged for centuries.

Klah died in February of 1937, just months before the Navajo House of Prayer opened. In 1939, the name changed to the Museum of Navajo Ceremonial Art. In the same board meeting where the name change took place and was voted on (too many visitors thought the museum a cult, they said), Klah’s multistrand necklace, by then gifted to Wheelwright, was accessioned to the Museum along with another necklace and set of “ear strings.” Now, Klah’s beads are on display as part of the Jim and Lauris Phillips Center for the Study of Southwestern Jewelry in the permanent Martha Hopkins Struever Gallery.