The decline of the Colorado River through drought and other factors has prompted artists to call attention to this event. Does art have the power, though, to mitigate the crisis?

Silver River

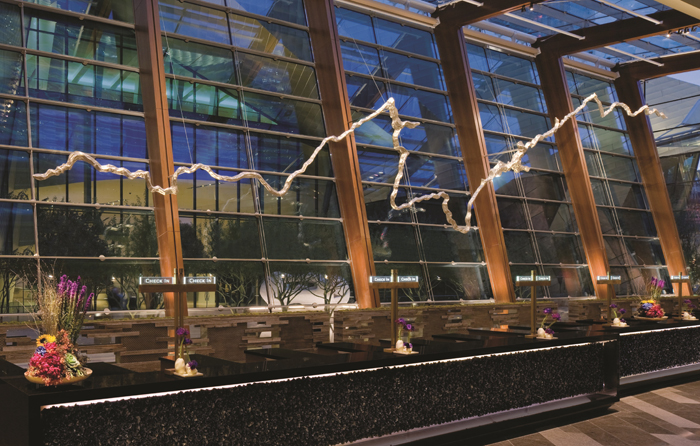

American artist Maya Lin created Silver River in 2009, an eighty-four-foot-long, 3,700-pound sculpture of recast silver that follows the topographical meanderings of the Colorado River. It was acquired by MGM Mirage as part of their $40-million public art program and can be found floating above the registration desk of the Aria Resort and Casino in Las Vegas, Nevada. Once seen as a work of art, it’s hard to take your eyes off Lin’s work: it glistens and draws points of light to its irregular surface, mimicking the flow of water, the fluidity of silver in a solid state. It is a river frozen in time, a time when the Western drought that is ongoing was still young.

Standing in front of Silver River, it is hard to discern at first glance you’re viewing a work of fine art. The intentionally destabilizing nature of casino interiors permeates Aria’s main lobby and registration desk, where a visual cacophony of people, sounds, and larger-than-life rotating installations reign. Despite windows, skylights, and glass doors flooding the space with natural light, the interior feeds on a certain level of chaos; the registration desk is a stream of people, computers, cables, and window fixtures. To state the obvious, the viewer is not in a sanctified art-viewing venue when encountering this work.

Lin has been quoted acknowledging, “This is not my typical venue, so one of the curiosities will be to see whether people coming here are curious enough to ask what it is if people ask why is she focusing on the Colorado River. That’s something that is a little bit of interest to me, to see how people react to a work of art that is pointedly focusing on an environmental issue within Las Vegas.”

Discreetly positioned adjacent to the Aria’s reception desk is a wall plaque for Silver River: “This eighty-four-foot, reclaimed silver cast of the Colorado River exemplifies both CityCenter’s commitment to sustainability and the artist’s commitment to the environment.”

It has become apparent that the future as portrayed through dystopian fiction might read now more as fact.

One nickname for the state of Nevada is the “Silver State,” based on the discoveries of silver by Euromericans beginning in 1858. The Comstock Lode, silver ore discovered in 1859 near Virginia City, Nevada, led to a series of cascading events that resulted in the rapid expansion of the state. That growth was advanced by colonialism and the capitalist prerogatives of extraction and mining.

Silver River is just one of Lin’s works on waterways, joining investigations and interpretations including her solo exhibition Maya Lin: A River is a Drawing at the Hudson River Museum in 2018. Site-specific works are one of Lin’s many strengths: the renditions of the Hudson River continue her practice of using unique static materials (in this case, marbles) to represent the flow and movements of water.

Lin’s career as an artist, architect, and environmental activist is well known. She continues to work across media and disciplines to share her views on the necessities of environmental wholeness and repair. She has collaborated with scientists and created the elegiacal site What Is Missing? (whatismissing.org, launched the same year Silver River was installed). This ode to the planet—crossing vast swaths of time and all geographies—follows a long line of memorials created by Lin, starting with her career-defining work, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, dedicated in 1993. The throughline of detailed attention and care for the way we interact with nature and how we can become engaged in its healing is important to Lin.

Colorado River

Lin accepted the opportunity to create a work on the Colorado River due to the environmental challenges being discussed at the time. Since 2009, the river has continued its downward trajectory of water loss, one of many bodies of water and waterways in the Western United States suffering the same fate. A confluence of factors—from the long, ongoing, climate change–fueled drought that was visibly noticeable in 2002 to increased population resulting in higher human water use and overconsumption—have led us to today, when news of the Colorado River crisis is found daily across multiple outlets, making it difficult to keep track of the myriad ways the decline of the river will present.

There are hard numbers attached to the river, which shift upward or downward depending on the day and topic. The river originates in Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park, ending 1,450 miles later after traversing south, west, and southwest to the Gulf of Mexico. Although these days, the river ends before reaching this historic destination in Mexico due to drought. It passes through Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and California, providing drinking water to approximately 40 million people, a number that continues to grow. The Colorado River Basin includes twenty-nine federally recognized Indian tribes. According to the University of Montana’s Center for Natural Resources and Environmental Policy, these tribes own rights to approximately 20 percent of water in the basin. The decline of the Colorado River, and the possibility of its drying up, are of grave concern to residents, landowners, policymakers, and agriculturalists. And to the rest of the 40 million of us who drink water.

You may know the river from any number of iconic images. It is the defining feature of the Colorado River Basin, a region spanning 246,000 square miles. Depending on its locality, it gushes and ruts, cuts and carves, ripples and stops, flows and flounders, a vital source of sustenance for all manner of flora and fauna. Water’s capacity to shape stone and carve canyons is remarkable, with the Grand Canyon just one example of this river’s powers to amaze. Deserts and alpine regions form part of the topography, while humans have played a role in reapportioning the river through damming, adding the destinations of Lake Powell (Glen Canyon Dam) and Lake Mead (Hoover Dam). Cities developed near its shores, including Las Vegas and Phoenix, two of the largest.

Art communicates viscerally to people when the same message presented through science, or the media, might be ignored.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the water level of Lake Mead was 1206.40 feet in mid 1999. In November 2009—the year of Lin’s installation at the Aria—the water level was 1093.20. In 2022, it dropped to 1043.27. The drop has led to discoveries some people have assumed were long buried, including sunken boats and human remains.

While stories of bizarre discoveries in Lake Mead are uncovered, it has become apparent that the future as portrayed through dystopian fiction might read now more as fact. Paolo Bacigalupi’s 2015 dystopian climate sci-fi novel The Water Knife pits characters against each other and nature as the Colorado River barely flows, drying up well before reaching Mexico. Science fiction is rapidly approaching reality.

That reality is grim. Joshua Partlow wrote in early December 2022 in the Washington Post, “Officials fear ‘complete doomsday scenario’ for drought-stricken Colorado River.” It’s hard to find the silver lining.

Along the Colorado

The number of individuals and groups engaged in the Colorado River is extensive and growing. While Lin presents one artist’s view through Silver River’s scale, situation, and name recognition, additional representations and interpretations of the river have been in the making.

Las Vegas artist and curator Sapira Cheuk has had water on her mind for some time. In 2020, she filmed fountains and water features along Las Vegas’s Strip, informing me, “they are in fact a false promise of plenty, a glittering veil that disguises the desert just outside.” Inspired by the centennial of the Colorado River Compact Agreement in 2022, Cheuk decided action was warranted to talk about the crisis using her expertise in art.

Through a combination of open call and selection, a group exhibition of twelve individuals was formed to address the current state of the Colorado River and the myriad ways we interact with, consume, and consider this resource. The result is the traveling exhibition Along the Colorado, which began in Nevada Humanities’ Las Vegas office in 2022, continuing to its second venue at Diana Berger Gallery, Mt. San Antonio College in Walnut, California. It concludes at Vision Gallery in Chandler, Arizona in 2023.

Cheuk drew upon her extensive network to ensure a wide range of media and content that would effectively tell stories about the Colorado River. Artists, scientists, and advocates represent the current crisis through “the scarcity, commodification, conservation, legality, and politics of water use,” according to Nevada Humanities’ website.

Visiting the exhibition at Nevada Humanities’ modest 500-square-foot gallery/office space, I was struck by the various artistic gestures artists used to talk about the river. Jen Urso’s installation, a multi-tiered map of water use in Phoenix, layers information from 450 CE to the present, from the Ancestral Sonoran Desert People to today. Information on crops native to the region completes the installation. Alexander Heilner’s long-term documentation of the Colorado River results in beautiful photographs that tell the story of decline and disrepair. The blue objects found in Marc Wise’s photographs are road reflectors, displayed (according to his statement) “to further illustrate the displacement of this most vital resource in the western United States.”

Each artistic gesture engages our contemporary crisis. In one communication with me, Cheuk stated: “I don’t think art in a gallery space will have the same direct impact as say, the PR team at Southern Nevada Water Authority, but those who encounter the work do end up talking and thinking about these issues. And the works lead us to talk about and connect with this issue in a deeper, more profound and expanded way than a billboard ever could.” She is also aware of the impact of discussion across various disciplines: science may have the data but may not be able to tell the story effectively—not as effectively as art.

These two artistic projects—from 2009 and 2022—bookend one investigation into the power of art to enact change in our ever-changing world of climate crises. They also illuminate two of Las Vegas’s art worlds: work displayed by internationally recognized artists such as Lin (and Sanford Biggers, Nancy Rubins, Frank Stella, and James Turrell, to name just a few) bought and installed on the Strip; and art created by local artists and communities for venues off the Strip.

For years, I have questioned the role and efficacy of art to address current events and enact meaningful change. Art’s venue, its market value, and/or status don’t matter to me as much as its power to change people’s minds, to lead them to the new ideas and practices required to secure—and in some cases, rebuild—our natural resources. I agree with Cheuk: art communicates viscerally to people when the same message presented through science, or the media, might be ignored.

If we care, we act.

There are pitfalls, though, in laying the weight of the climate crisis on artists. It can be hard to posit solutions amid the daily onslaught of regional and international environmental degradation. It’s not up to artists alone to shine that bright and glaring light: with a more critical eye focused on Lin’s work, and her deep commitment to the environment, the Aria could be a partner in promoting Lin’s concerns. It is to Lin’s credit, though, and Cheuk’s curatorial vision, that they engage scientists and others in the dialogue. The interdisciplinary nature of their works can fill in the gaps where just one discipline might fail.

An article published in late November on the occasion of Lin’s solo exhibition at Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery may provide another answer to the question of art’s power. Reporter Chloe Veltman wrote for Georgia Public Radio (a PBS, NPR affiliate): “Lin said the best way to inspire people to action is through generating empathy.”

Promote empathy. If we care, we act. Reading this statement provided the hope I was seeking to continue the work (and to continue writing this article under the weight of daily doom and gloom). In the midst of our transactionally oriented lives, here’s to hoping that an empathetic stance can be injected, then normalized. It shouldn’t be such a long leap from transactional actions to those focused on a sustainable future.