Multimedia artist Tyler Burton mixes methods to create sculptural works that communicate the effects of climate disaster on California landscapes and move towards mending our relationship with the land.

There is a quotation by the painter Robert Motherwell taped near the front door of Palm Springs, California-based artist Tyler Burton’s studio: “It’s not that the creative act and the critical act are simultaneous. It’s more like you blurt something out and then analyze.”

Burton is a thoroughly intuitive artist, taking her cues from her surroundings and materials. I ask her why she thinks her work has changed so much—evolving from smaller, figurative pieces to larger, abstract ones—since she moved from Los Angeles to the desert eight years ago. “That’s when the environmental shift happened in my work,” Burton muses. “Being out in the big open desert with the big sky, I’m much more connected to nature than I was when I lived in L.A.”

The artist spent twenty-some years based in Los Angeles and still travels between San Clemente, Lake Tahoe, and Palm Springs. With the physical space and inspiration to go bigger in the desert, Burton combines clay, metal, photography, and video—and pulls from an ever-evolving collection of found objects—to create restorative, often large-scale sculptural works highlighting California’s environmental crises. She groups most of her work from recent years as “Projects for the Anthropocene,” with three distinct series focused on the environmental impact of single-use plastics, the water and shelter in California, and the effects of wildfires across the state.

A photographer by training, Burton has invariably gravitated toward tactile processes. “It was always about the darkroom for me,” she says, showing me a cyanotype print of plastic bags and water bottles, which looks eerily like an x-ray. “I started moving back and forth between media, doing the print and clay work together. I love going back and forth—I’m a materials artist.”

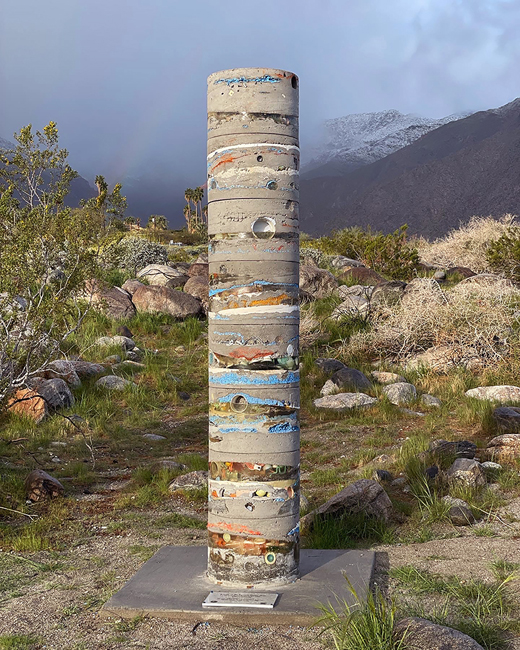

Today, found materials are the foundation of much of Burton’s work. Her Fossils of the Future series, exhibited by the city of Palm Springs and the Pacific Design Center in Los Angeles, examines the ubiquity of single-use plastics and has even become a repository for refuse. On one side of her studio, a tall, cylindrical form stands at nearly eight feet tall, stacked with strata of concrete and fluorescent plastic. Looking closer, I can see other, unnatural inclusions: gold plastic shamrocks; the white lids from prescription pill bottles; a small figure of Buzz Lightyear.

“I fill these with recycled plastics,” Burton explains. “It started with plastic bottles, seeing them everywhere, people taking three sips and leaving them. The other things come from found and donated objects; for instance, the lids came from a pharmacy. They were coming out with a giant bag of them because they were the wrong size and they were just tossing them.” Now, friends bring her all sorts of trash they find in the desert—Burton’s work has become an alternative recycling method.

She gestures toward the sculpture, which is hollow. “There’s the plastic you see, but there’s plastic filling it, too. This way the plastic is contained, it’s disposed of, and it makes the piece lighter. It feels good—I’m putting it all in my art.”

Burton wants her art out in nature, reintegrated into the landscape—and wants to see others physically engage with the work. Her studio will be included in Desert Open Studios from January 26-28, 2024, and during Modernism Week on February 23-24, 2024.

In the studio, Burton walks over to a desiccated, charred tree trunk, which I notice has been reinforced with metal along its base. This is one from her Artifacts of Fire series—an ode to the widespread destruction of forest areas in recent years. This particular tree came from Blackwood Canyon near Lake Tahoe; Burton pulled it from a burn site herself.

The metal in the sculpture is Burton’s addition. “It’s a form of armor,” she says, “to protect the tree and honor it.” The other sculptures in the series have metal inclusions, too, like alloys melted and dripped into the fractured wood.

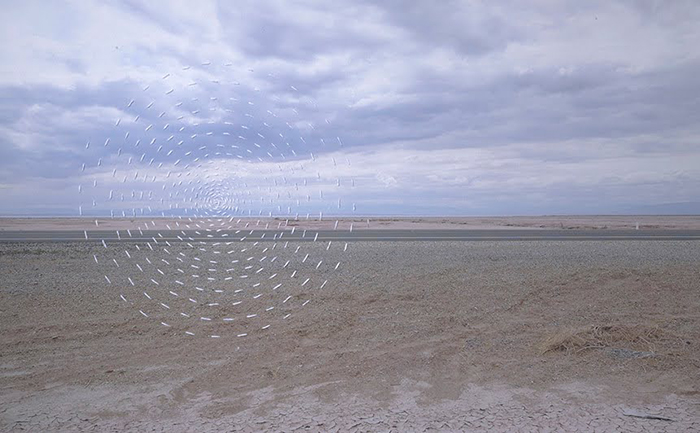

The reparative motive is clear across all of Burton’s work. The third component of her Anthropocene project is Places: California Water, a series that explores the effects of water crises, especially at the Salton Sea, which stretches across Riverside and Imperial counties. The Salton Sea—technically California’s largest lake—was formed when flood water from the Colorado River broke through an irrigation canal in 1905. Chemical-filled irrigation runoff fed the Sea for years after, and because it had no outlet, the water turned highly saline; at the same time, the Sea became an important habitat for hundreds of fish and bird species.

These days, the Salton Sea is mostly dry. “The sand left behind is filled with arsenic, cadmium, all kinds of bad chemicals,” Burton explains. “The wind blows it everywhere.” (According to a 2023 National Institutes of Health report, the asthma rate for children living along the southern portion of the Salton Sea is twice the national average.) People and animals have abandoned the area as a result. When she first started going to the Salton Sea, Burton found the things left behind. “In the houses, there was canned food in the cabinets,” she recalls.

Burton used a fragment from the ceiling of one home for one of the sculptures in her studio; it stands on clay feet—a humanization of the residents’ flight from Bombay Beach, a bustling tourist center turned ghost town. Nearby, a series of abstract “birds”—small ceramic forms mounted on metal tripods that wiggle when you push them—honor the species that no longer migrate to the area.

A photograph of Owens Lake, another defunct body of water near Mammoth Mountain, hangs on a wall across the room. Plastered with red and blue produce netting and stitched with multicolored thread, the piece is emblematic of the literal and symbolic mending Burton enacts through her work. With each stitch, Burton begins to mitigate the damage inflicted on the California landscape and its inhabitants—and sends a beacon of warning.