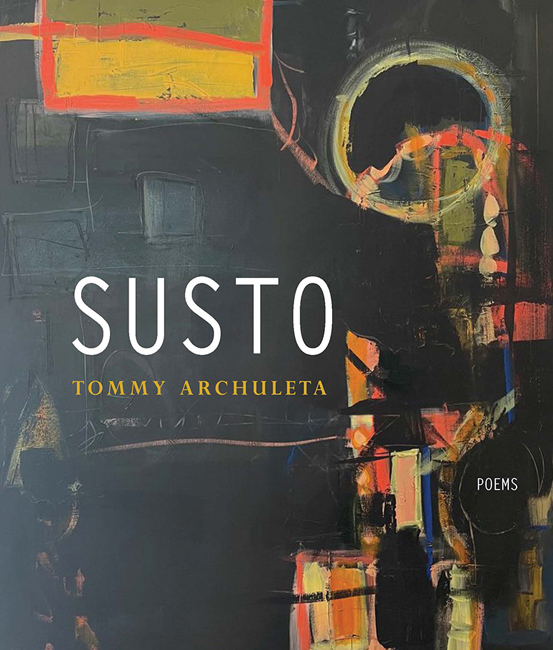

Tommy Archuleta’s debut poetry book Susto delves into the science and folklore of curanderismo to take readers on a magical and frightening journey through grief.

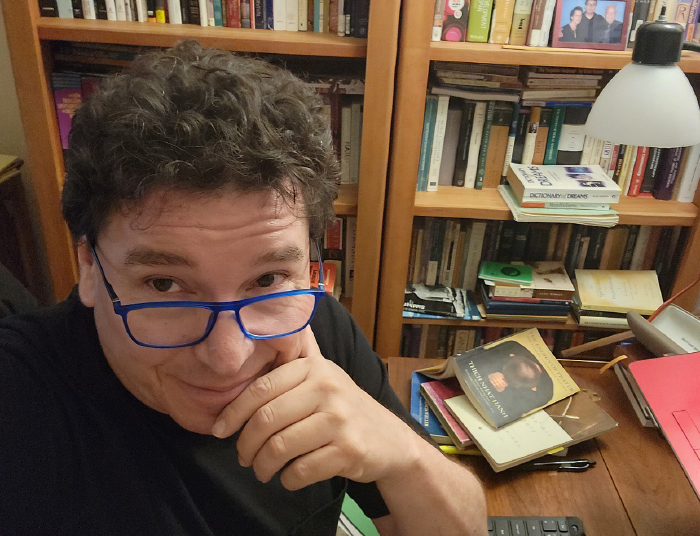

SANTA FE—For Tommy Archuleta, writing is ritualistic. He rises two hours early, ahead of his 8 am workday as a mental health and substance abuse counselor at the New Mexico Corrections Department, to mediate, practice gratitude, and write poetry. He started this routine in 2014 when, while grieving his mother’s passing, he began writing down short, lyric poems first thing in the morning. The poems marked the beginnings of what would become his debut poetry book, Susto, which is now making its way into the world as the latest Mountain/West Poetry Series selection from Colorado State University’s Center for Literary Publishing.

Susto is a spellbinding book that leads the reader on a magical and frightening journey through grief. It is also steeped in the landscape and traditions of Northern New Mexico and in curanderismo, which Archuleta describes as a “folk medicinal art form” with a long history in the Spanish culture and “ties going all the way back to Aztec and Mayan civilizations.”

Over a Zoom interview, Archuleta, who was born and raised in Santa Fe and currently resides on Cochiti Reservation, spoke with me about his book and writing life.

“I started late in school,” Archuleta says of his formal education. He describes himself as a restless teenager who dropped out of high school at the age of seventeen to play music and tour with the cowboy punk band, 23 More Minutes. “I was one of those that just couldn’t stop using drugs and drinking,” he says of those years. “I ended up finally, thankfully, getting clean and sober at the age of thirty-three.”

A friend in recovery gifted him a book of poems by Pablo Neruda, which led Archuleta to the local library poetry stacks and, ultimately, down a new life path.

When his first poem was published later that year in the Manzanita Quarterly—a now-defunct regional literary journal—while he was in his mid-thirties, “No one was more surprised than I was,” he says. Shortly after publication, Archuleta enrolled in the College of Santa Fe, where he says he was offered a full-ride based on the merit of his writing.

After graduating with his bachelor’s degree, he struggled with what he was going to do professionally, but eventually found his footing when he entered the field of recovery, first as a med tech and then as a counselor. He was set to enroll in a master’s in counseling program when his mother, whom he had been caring for, passed away in August 2013. Her death launched him into a profound state of grief.

In January 2014, he began the master’s program at New Mexico Highlands University. During his graduate studies he encountered a definition in the fifth and latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, which had begun including culture-based conditions, one of which was susto.

“[The definition] basically stated that, in some Latinx countries, one can undergo a traumatic event that is so jarring that the soul and the body separate. And it can happen also through repeated traumatic events. And it can be so disorienting that one cannot know what to do,” Archuleta says.

“And when I read that, I knew that that was the title of the book, but I also realized that was the description of how I felt. Because I’ve never felt that level of grief before,” he says. “As I’m progressing through my grief, and I’m progressing through my graduate work, I’m also being led through this journey of the book.”

The manuscript, begun in 2014, would undergo numerous revisions. “By the time COVID hit, the work started to look different,” he says. “I actually contracted COVID and gave it to my father, and we both were hospitalized.”

“I remember seeing nurses pushing these respirators at a running pace down the hall. I was essentially surrounded by death and that has a way of changing your perspective,” he says. “And when I came back, the most recent draft of Susto started looking different… it seemed to be asking different things of me.”

A late discovery of his mother’s books on remedios (or cures), which she used while practicing curanderismo, also offered new questions and helped shape the book. As he continued to revise the poems and rework the manuscript, Archuleta says, “I started to feel that this work was way bigger than I was.”

Near the end of our interview, I hesitantly ask Archuleta whether he found the writing of the book to be healing. Surprisingly, without missing a beat, he answers, “Yeah, absolutely.” He refers to his “practice of waking up two hours before I needed to” to work on the book.

“I still do the practice,” he says. “I sit down and write and it is healing because it’s become a part of my spiritual practice. Just plain and simple.”

It is this access to the spiritual and the unseen that perhaps has and will continue to bring Archuleta back to the page. As he says, “One of the challenges of poetry is trying to put words to the ineffable and trying to bring out or hopefully touch things that are not really readily available, whether to the eye or to the heart, but they’re there.”

On Thursday, April 27, 2023, at 6 pm, Archuleta is scheduled to appear at Collected Works Bookstore and Coffeehouse, 202 Galisteo Street in Santa Fe, for a reading and conversation with poet Dana Levin.