Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, Alabama

January 28, 2017–January 6, 2019

For the past several years, the Birmingham Museum of Art has been quietly amassing a powerhouse collection of some of the most significant politically inflected art of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Works by Radcliffe Bailey, José Bedia, Dawoud Bey, Nick Cave, Amanda Ross-Ho, and Mickalene Thomas have been drawn from its collections for inclusion in Third Space. The exhibition draws parallels between the American South and the Global South. Curator Wassan Al-Khudhairi conceives the latter not as a geographic place so much as a conceptual space wherein issues such as racial violence, migration, and poverty converge and intermingle to form new connections.

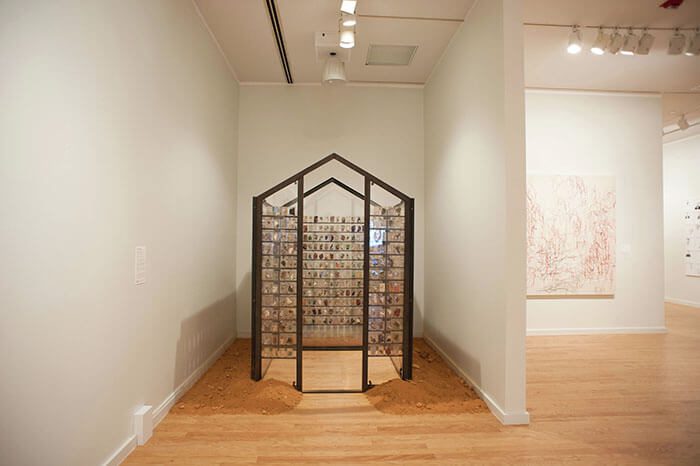

The installation is a sort of memory palace, a reliquary of visual and auditory fragments of a site that no longer exists, but that was once home to many.

One of the most prominent works in the show is Mel Chin’s The Sigh of the True Cross (1988), a large multimedia sculpture resembling both a hammer and sickle and an Ethiopian musical instrument, the masinqo. These images, along with the title’s reference to the Red Cross, symbolize Ethiopia’s civil war and famine of the early 1980s. Sue Williamson’s Mementoes of District Six (1993) is a house-shaped structure constructed from small Lucite bricks containing remnants of the eponymous Cape Town, South Africa, district destroyed during apartheid. Stepping inside the house itself, visitors can hear recordings that Williamson made in District Six in 1981, before its inhabitants were displaced. The installation is a sort of memory palace, a reliquary of visual and auditory fragments of a site that no longer exists, but that was once home to many.

Birmingham is acutely aware of its history and relationship to the civil rights movement, and many of the artworks in Third Space confront the role of the American South in the United States’ racial history. Kerry James Marshall’s As Seen on TV (2002), for instance, directly alludes to the 1963 bombing of Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. The multimedia work includes a scaled-down replica of the church’s cross-shaped sign (which still hangs on the church, located less than a mile from the museum) adorned with a funereal bouquet of flowers. More broadly, Jefferson Pinder’s Sean (Mercy Street) from the Juke Series (2006) features a black man lip-syncing to Johnny Cash’s song “The Mercy Seat.” The tight shot of his face expressively mouthing the lyrics, the last words of a man facing execution in the electric chair, evokes at once the history of lynching; Birmingham’s own electric chair, famously named the “Big Yellow Mama”; and the mass incarceration of generations of African American men in the U.S. Within an exhibition that addresses systemic racism across the world, the United States’ specific civil and human rights issues take on new meaning for our current political moment.