Pavements, holes, trenches, mounds, heaps, paths, ditches,

roads, terraces, etc., all have esthetic potential.

Robert Smithson

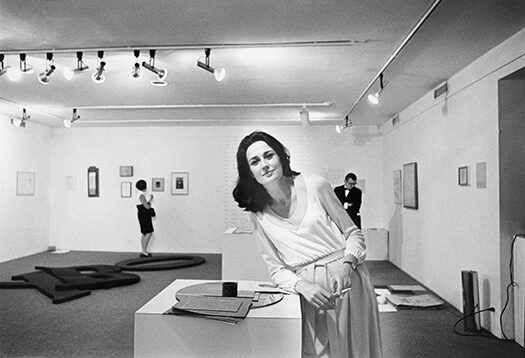

Los Angeles to New York: Dwan Gallery, 1959–1971 is a bold and illuminating exhibition in honor of Virginia Dwan and is now at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC (NGA), where the exhibition first opened in 2016 before coming to LA this past spring. The NGA will become the recipient of Dwan’s collection and her archive culled from her storied career as a visionary gallerist, patron, collector, and towering figure in the history of contemporary art in the second half of the twentieth century. This gift to the NGA is an astonishing and supremely important one whose value would be difficult to calculate, encompassing as it does work that Dwan not only presented in her series of landmark shows, but pieces that she chose with her discerning eye for her own personal collection. Nonetheless, Dwan’s presence and importance can seem somewhat illusive because, while she was at the center of a very heady and boundary-breaking period of Contemporary art, her good looks, uncommon grace and poise, and her unobtrusive nature may have served as a form of camouflage when you positioned her next to the outsized egos of artists who were changing the rules of the traditional gallery-centered game. For her own part, Dwan was blessed with a probing spirit and she was willing to take extraordinary risks.

Virginia Dwan, born in 1931, beautiful, intelligent, wealthy, and adventuresome, could have become anything she wished. Yet, as a young woman she wound up reserving her energies to promote the production of visual culture, continually raising her own stakes in the art of discriminating taste as a form of moral compass. If I were to conjure one image of her from my own imagination, it would be Dwan following the growling voice of Robert Smithson as a clarion call to experience art as a series of depth charges hurled into the waters of the avant-garde. In the blowback, there would emerge the concept of artistic vision as an exploration of the limits of art. Eventually, Dwan would become the snake that bites its own tail in a series of artistically svelte moves demonstrating that she was, and still is, a “spiritual athlete” all along.

Moving slowly through the various sections of this extraordinary exhibition at LACMA, the scope of the work that Dwan exhibited, promoted, funded, and collected is, in a word, staggering. She was very much an avatar in the art world as it was unfolding back in the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s—certainly a heady time to be involved in the many-headed beast that contemporary art had become. And the work that Dwan championed has taken its place as some of the most influential and iconic artwork of the last century, made by individuals such as Robert Rauschenberg, Edward Kienholz, Claes Oldenburg, Donald Judd, John Chamberlain, Sol LeWitt, Agnes Marin, and Andy Warhol—and on to the monumental projects by Charles Ross, Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria, and Robert Smithson. If Dwan were known for her association with only one work from the twentieth century—Spiral Jetty—that would have been enough to cement her place in the new world order of contemporary aesthetics that the genre of Earthworks embodied.

The LACMA exhibition showcases a number of Smithson pieces besides the visual references to Spiral Jetty (1970), including the artist’s documentary on the making of the work, emphasized by Smithson’s hallucinatory high-key voiceover. But, without the support of Dwan, would this project have ever come to pass, entailing as it did the leasing of the land in the Great Salt Lake; the hauling of the boulders; the front loaders and dump trucks; the aerial flights both before and after completion; not to mention the immense planning and plotting and scheming to bring to fruition this visionary work? That said, Dwan’s support of other extremely ambitious Land Art projects, romantically inaccessible and conceptually difficult, still carries the weight of the prophetic dialectics that must have occurred between artist and patron—think of Heizer’s Double Negative (1969) and his Displaced–Replaced Mass (1969); Ross’s Star Axis (begun in 1971 and ongoing); and De Maria’s first lightning field called 35–Pole Lightning Field (1974). These are works of singular importance that loop back into the history of monument building—a history that is thousands of years old. And, to be more precise, it was Dwan who held the first exhibition of Earthwork art in New York, in 1968.

Back Seat Dodge ’38 caused quite the controversy when it was first shown, prompting the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors to demand that the piece be taken out of the exhibition, while also risking the arrest of Dwan and the artist.

Dwan’s restless and radical eye for ground-breaking art (literally and figuratively) also found its way into the spheres of Minimalism, avant-garde expressions from Europe, the arena of art and language, and Pop art. She was the first gallery owner in Los Angeles to exhibit Warhol’s Brillo boxes, and she had, by 1962, also begun showing work by Kienholz, most notably his Back Seat Dodge ’38 (1964), an installation that still has the capacity to disturb in its depiction of adult sexual activity taking place in the squalid back seat of a car that Kienholz altered for his purposes. Back Seat Dodge ’38 caused quite the controversy when it was first shown, prompting the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors to demand that the piece be taken out of the exhibition, while also risking the arrest of Dwan and the artist. This infamous and provoking work is part of the current LACMA survey, and, although I had seen many reproductions of it, I wasn’t prepared for the level of queasy pathos that still surrounds the piece. Its soundtrack of music from the 1940s spills into other parts of the exhibition and it’s as if in the music itself the ghost of Kienholz won’t let you forget the sordid misery that issues related to furtive sex have generated over time.

The exhibition begins not with topical issues, however, but in the realm of pure light and its intangible, otherworldly effects. At the formal entrance to Los Angeles to New York are six large Plexiglas prisms by Charles Ross, standing like mystical sentinels, and titled Six Prisms from the Origin of Colors (1970/1988). Dwan’s patronage of Ross’s Star Axis is part of its history, but she has worked with Ross on another project, more recently begun, that also features huge prisms installed in a permanent architectural setting, and this will be discussed later. Star Axis itself is located on a mesa near Las Vegas, New Mexico, and, once opened, will be a large-scale observatory for celestial phenomena.

Alongside the work that Dwan showed in her East and West Coast galleries, there are also maquettes for gallery invitations, old-fashioned-looking ledger books with installation plans, and various guest books—one of which was open to a page with signatures by, for example, Marcel Duchamp, Lucy Lippard, and Clement Greenberg. Indeed, the LACMA exhibition of Dwan’s multiple endeavors encapsulates a sizable chunk of the contemporary cultural landscape, sweeping along artists of so many persuasions and highlighting pieces of the art puzzle that they helped to define—from the austere minimal work of Sol LeWitt, Agnes Martin, and Fred Sandback, to Carl Andre’s sixty-four-piece floor grid fabricated from hot rolled steel and an aloof diptych by the painter Jo Baer.

From this exhibition one gets the distinct impression of how physically and psychologically involved she was with her artists—how hands-on she could be in her role as enthusiastic facilitator and sophisticated presenter of art that pushed and then rolled over its boundaries so that new layers of aesthetic possibilities could emerge.

It seems that there was no limit to the kind of art that stimulated Dwan’s imagination—from the freewheeling Combines of Rauschenberg to the nearly invisible thread pieces of Sandback, to the conceptual wordplay of Joseph Kosuth in a text piece called Titled (Art as Idea as Idea) [real] (1968). Dwan also presented four shows that featured art and language pieces, and one “Language” show presented Arakawa’s Untitled (Stolen) (1969), which included the following directive: IF POSSIBLE STEAL ANY ONE OF THESE DRAWINGS INCLUDING THIS SENTENCE. Also presented in one of the “Language” shows was a painting by Mel Bochner, Language Is Not Transparent (1970), whose text Bochner appropriated from a graffiti slogan someone had spray-painted on a wall in Paris during the student protests in May 1968.

The importance of Dwan’s legacy as a curator, generous patron, gallerist, and collector cannot be overestimated. And from this exhibition one gets the distinct impression of how physically and psychologically involved she was with her artists—how hands-on she could be in her role as enthusiastic facilitator and sophisticated presenter of art that pushed and then rolled over its boundaries so that new layers of aesthetic possibilities could emerge. Perhaps, in the end, though, one of the works that Dwan will most be remembered for is her collaboration with Ross and the architect Laban Wingert in the creation of a quiet place of reflection, an elegant and metaphysically expansive building open to all. On the campus of the United World College in Montezuma, New Mexico, is the Dwan Light Sanctuary (1996)—an ethereal space of great and inspiring beauty that Dwan also helped to design.

For this building, Ross created twelve large prisms that are installed in various parts of the open-plan sanctuary so that a progression of prismatic colors glides over the walls, ceiling, and floor in this large, circular ecumenical room. The prisms are aligned to the sun, moon, and stars, and there is an almost supernatural aura that pervades this meditative chamber—that also happens to be acoustically resonant and perfect for singing, chanting, or recitation. In truth, the Dwan Light Sanctuary has another kind of alignment, as well, in that it isn’t all that far away, as the crow flies, from Ross’s Star Axis. The latter work is ambitious on a grandiose scale, while the far more diminutive Light Sanctuary is tucked away among the trees of a school campus and accessible to anyone who cares to make the drive. But the sanctuary is vast in its own way, too, and could be thought of as a satellite entity, separate but equal, to Star Axis and equally as expansive in its intentions. The impressive observatory, when completed, will metaphorically project us out into the seemingly infinite reaches of our galaxy, while the Dwan Light Sanctuary, very much in the here and the now, helps to project us into the inner reaches of ourselves. The two works offer the intense and complementary experiences of leaping off the edge and into the world of the unknown and the speculative, twin concepts always at the heart of all visionary work. If Star Axis is about the coolness of immense timeframes and provocative intellectual reckonings, the Dwan Light Sanctuary is like a cradling womb, albeit no less impactful in its intimacy, because of its highly personal vectors and valence of dreams.