A tragic awareness haunts every element of the opera Doctor Atomic. The libretto, the music—the tableaux of singers, dancers, scenes, and the one prop that never ceases to cast its shadow on the whole—press down on the audience right from the start. Although there are some moments of levity in Doctor Atomic, they are few and far between the escalation of tensions that proves to be one fulcrum of the work. The seriousness of the moment, when the transformation of matter into energy becomes more than hypothetical calculations on a page, clouds the unfolding of the narrative without letup. Doctor Atomic embraces a tragedy that the world has been doing its best and its worst to cope with for seventy-three years.

The opera, with music by John Adams and libretto by Peter Sellars, who is also the director of this production, is rooted in the origins of tragedy in ancient Greek theater—with its invention of the chorus that functions as a medium of human awareness and an omniscient commentator on the follies of mankind, just as the chorus of Doctor Atomic does. If tragedy is, in essence, about our relationship to the warping of our moral compass, understood as a form of death, or thanatos, tragedy does not exist in a void and is meaningless without its relationship to eros, or the life force, and the dance of eros and thanatos is like the twinning of our DNA. If Doctor Atomic is a tragedy of immense and august proportions, it is also a powerful love story, and an erotic current runs parallel to the struggles of the scientists to succeed in creating an atomic bomb. The men drag with them from scene to scene the intense moral dilemma at the very heart of the Manhattan Project, and it pushes and pulls the narrative of the opera to its conclusion.

One cannot listen to or watch this opera without that knowledge infusing one’s attention like the persistence of a very bad nightmare that one will never be able to shake.

Resolution, however, never comes, only a staggering sense of heartbreak and horror as the scientists succeed and the inevitable detonation occurs. A headline in the Santa Fe New Mexican, from August 6, 1945, reads, “Deadliest Weapons in the World’s History Made in Santa Fe Vicinity.” The deadliest weapons ever used on a civilian population leave Hiroshima and Nagasaki in smoldering ruins. One cannot listen to or watch this opera without that knowledge infusing one’s attention like the persistence of a very bad nightmare that one will never be able to shake.

Nonetheless, there is hope, isn’t there, in the continuity of various cultures? In the drumbeats, the dancing feet, the songs and prayers of the Native Americans? In the harmony of the strings, the electronic humming, the repetition of poetry, and the construction of the self through the multiple lenses of the artistic process? Having visions means many things to many people. There are numbers to crunch that drive the equations that turn matter into energy, energy into matter, and ideas that motivate a curious and speculative mind to encase those ideas in a variety of forms. In the case of Doctor Atomic, art is a great mirror of the inner life of the world of appearances.

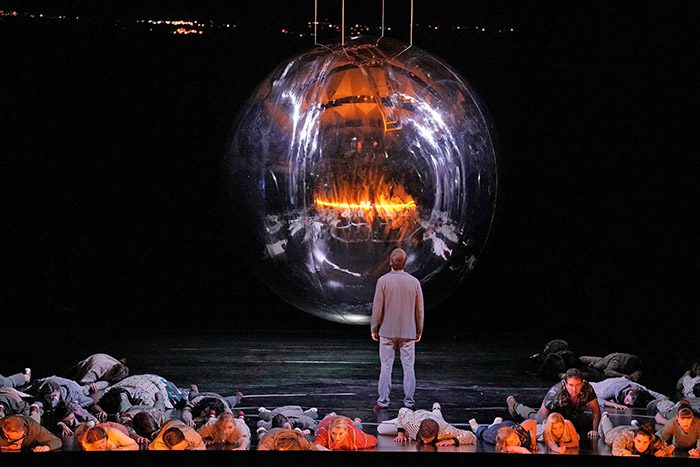

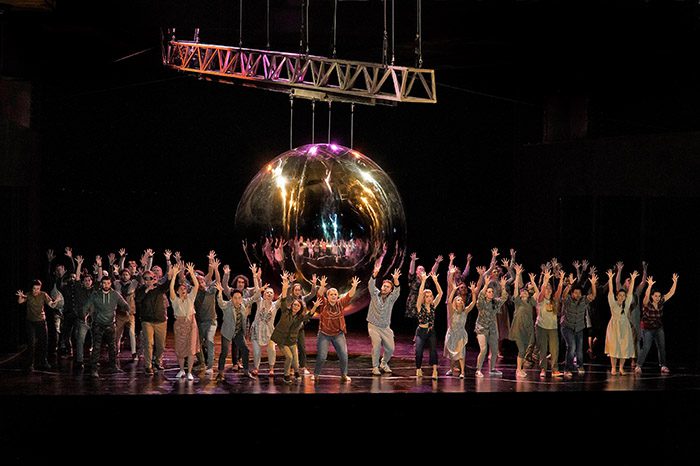

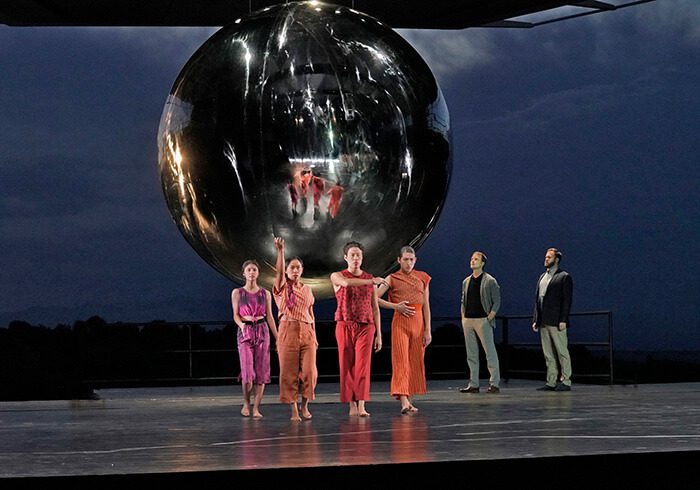

This silver sphere, spectacularly beautiful and horrific, is the critical mass at the center of all thought and action, reflecting everyone and everything that happens on the stage.

When I speak of art in relationship to Doctor Atomic, I’m referring to the totality of the opera. There is the complex and riveting music itself, conducted by Matthew Aucoin, the multi-directionality of Sellars’s libretto, and the individual characters—what actions they take, the set they engage with, the choreography, and the atmosphere that pervades the whole. And some of that atmosphere is provided by the landscape of New Mexico itself. In terms of setting, was ever an opera more at home than this one, unfolding as it does with the actual backdrop of Los Alamos off in the west? Then there is the huge, silver sphere, representing the first atomic bomb about to be tested at Trinity Site, hanging from scaffolding near the open wall at the back of the theater. “The Gadget,” as the bomb was nicknamed during the Manhattan Project, dominates the text, music, dance, poetry, and the underlying philosophical conflicts. This silver sphere, spectacularly beautiful and horrific, is the critical mass at the center of all thought and action, reflecting everyone and everything that happens on the stage. It is no empty cipher.

Richard Wagner also comes to haunt Doctor Atomic, especially through the role of Robert Oppenheimer, sung by baritone Ryan McKinny, who could be seen as a Parsifal for the Postmodern Age. Parsifal was Wagner’s last opera, bringing his life’s work to the cusp of Modernity. The character of Parsifal becomes involved with the knights who are searching for the Holy Grail. Besides redeeming himself for the thoughtless and forbidden act of killing a swan, Parsifal’s real task as “the holy fool” is to help heal the wounded soul of the world, mythically speaking. Parsifal is a work about humanity’s capacity for dedication to a higher purpose, as the struggles between the forces of light and dark must take place in order to insure the continuity of the world order and, by extension, its continual rebirth—a cosmological view that weaves through Doctor Atomic. Before Adams’s music unleashes its chromatic harmonies and plunging dissonances, there is a prologue of sorts, a ritual Corn Dance performed by members of Tesuque, San Ildefonso, and Santa Clara Pueblos. This added prologue in the Santa Fe production is, in the mind of choreographer Emily Johnson, an offering to the original inhabitants of the Southwest and a token of healing energy.

The set for Doctor Atomic is minimal; little is needed to flesh out the drama that begins in Los Alamos in early June of 1945 and ends at Trinity Site on July 16 with the first detonation. Besides the ever-present sphere, a bed and a chair are brought out for a couple of episodes, including the emotionally charged bedroom scene between Kitty Oppenheimer, sung by soprano Julia Bullock, and her husband, Robert. And here is an instance where poetry—in this case, words taken from poet Muriel Rukeyser—shines like a bright beacon of romantic love. One of the most purely lyrical moments of the opera is Kitty repeating a question as she sings to Robert, “Am I in your light….” This winding erotic thread is plucked by Adams and Sellars from a tapestry of various source material: poetry, archival text from the Manhattan Project, quantum mechanics, Pueblo song, and the news of WWII, always filtering into Los Alamos from Washington with its military justifications for creating a weapon of mass destruction. The Corn Dancers usher in a spirit of transformation, and they come back at the end on a stage crowded with cast, chorus, and downwinders from Tularosa who have never been properly acknowledged or compensated for the radioactive materials that floated their way after the bomb blast at Trinity Site.

One of the most haunting episodes in the opera is when Oppenheimer, in the hours before the Trinity test, sings John Donne’s famous poem, “Batter my Heart, Three-Person’d God”—a hallucinatory moment in Doctor Atomic as Oppenheimer mentally and physically grapples with the implications of what is about to happen; he appears to be literally wrestling with his feelings of hope and despair. This is one of many hallucinatory scenes in this stylized work that fuses its historical foundations with rich poetic and psychological overtones. The actual naming of Trinity Site is based on Donne’s “three-person’d God,” a symbolic allusion to the complex nature of spirituality.

Where does one go with this terrible knowledge, with this virtual-reality tour of nerve-wracking tensions and the profound moral struggles of everyone trying to justify and make sense of something that may yield such dire consequences for the future of the planet?

For all the historical and moral weight of Doctor Atomic, when the characters sing or there is a demanding orchestral interlude, a single unifying force is articulated through all the parts, and it is symbolized in the aura of the ravishing sphere—a cosmic eye that sees all and reflects all, as well as being the product of a devil’s bargain—this weapon of mass destruction. Each role—Kitty; her housekeeper Pasqualita; physicists Oppenheimer, Edward Teller, and Robert Wilson; General Leslie Groves; and meteorologist Frank Hubbard—offers a unique angle that reflects aspects of the domestic, scientific, and the military in America at that time. But each of these angles also suggests that perhaps no moment in the history of humanity could have been more freighted with the choices between life and the possible end of civilization. This is a theatrical work where there will be no catharsis.

The opera is indeed a resonant whole that creates a unified force field that the audience enters and, by the end, sad and searing as the ending is, has trouble exiting. Where does one go with this terrible knowledge, with this virtual-reality tour of nerve-wracking tensions and the profound moral struggles of everyone trying to justify and make sense of something that may yield such dire consequences for the future of the planet? In Act II, at Trinity, in the early hours of the morning of July 16, Robert Wilson—sung by the tenor Benjamin Bliss—a protégé of Oppenheimer’s and one of the most conflicted of the scientists, is perched on a tall ladder-like tower so he can reach the top of the sphere, attempting to make sure it’s stable. He sings, “I dreamed the same dream—and I’m at the top of the tower—and I’m falling… falling… falling…,” the word repeating in an exquisitely gentle refrain until Bliss’s voice trails off into the storm that rages around the test site. And then his voice is finally drowned out by Teller’s interjection, sung by the bass Andrew Harris, “Might we not be setting off a chain reaction that will encircle the globe in a sea of fire?” Oppenheimer answers him quickly, singing, “The Gadget won’t set fire to the atmosphere.” At this point, dissociation reigns. Everyone is dissociated from everyone else in the spell of this infernal instrument, whose true powers of destruction no one will ever know until it’s too late. The intuition of catastrophe is the psychic force that sends everyone flying apart from one another but that brings everyone together at the end of the opera in a tableau of bodies lit by the glow of a demonic light.

In Adams’s often hair-raising score, I was never more aware of an opera’s music being the virtual projection of yet another character and the ultimate carrier of meaning. So it is in Doctor Atomic: music not as background for the singers to either combat, transcend, or blend with, but a deus ex machina that gives life to all the fragments of the work and fuses them together into a single entity—Adams’s score is mysterious, nonlinear, and promethean in strength. On one level, Doctor Atomic can be interpreted as a swan song for the ending of one age of civilization and a simultaneous clarion call as another one begins its convolutions on a new plateau of mirrors. Or is the opera a magnificent alarm bell, tolling the perils of the Atomic Age and a world out of balance?

Suffice it to say that the ending of Doctor Atomic is rife with an apocalyptic intensity as sirens ring out, penetrating electronic sounds encircle us, the bomb is detonated, and then all is silence for a few moments—until a woman’s recorded voice speaks softly in Japanese. The words are few but they are shattering. And that is as it should be: the inclusion of these words in Japanese embodies a piercing empathy that is a theme of the opera in this era of chained reactions where the angles of incidence will always equal the angles of reflection.