The Hiroshima Library is a library (kind of), art installation (we think), reading room, and place for contemplation created by Brandon Shimoda at Counterpath in Denver.

“The Hiroshima Library. I would LOVE to talk with you about it,” Brandon Shimoda, creator of the Hiroshima Library, tells me. “It’s not something that people ever ask me about, maybe because I never talk about it, but—in a way—prefer it to exist without announcements or pronouncements.”

This quasi-paradoxical statement makes writing about the Hiroshima Library a bit complicated. How do I write about something that is designed to be unnoticed and undescribed? Like explaining a joke, I risk removing everything spontaneous, unexpected, and surprising. On the other hand, a visit to the library is so personal that there may be no way to describe it at all.

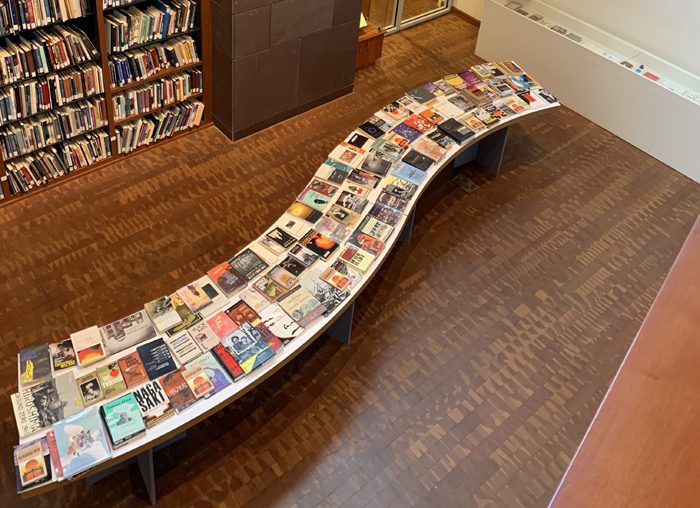

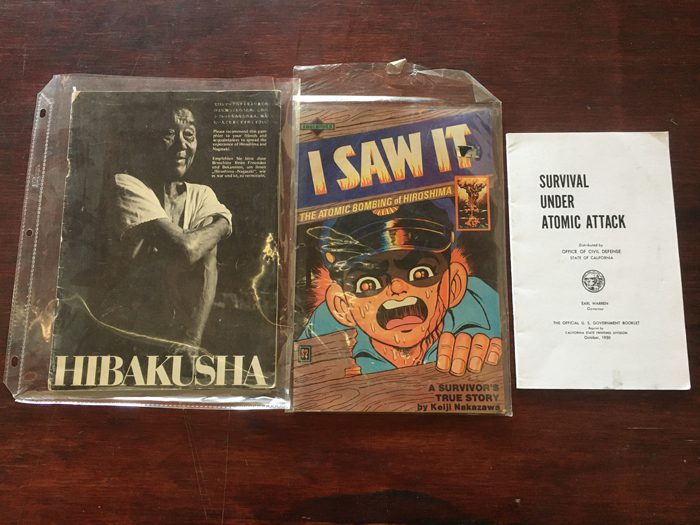

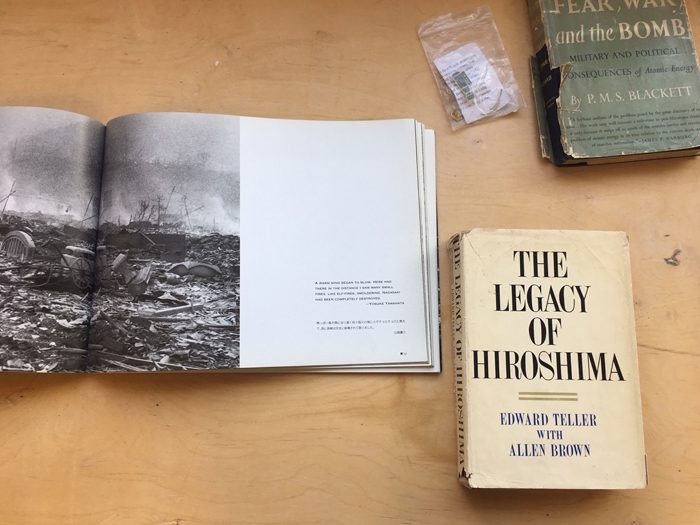

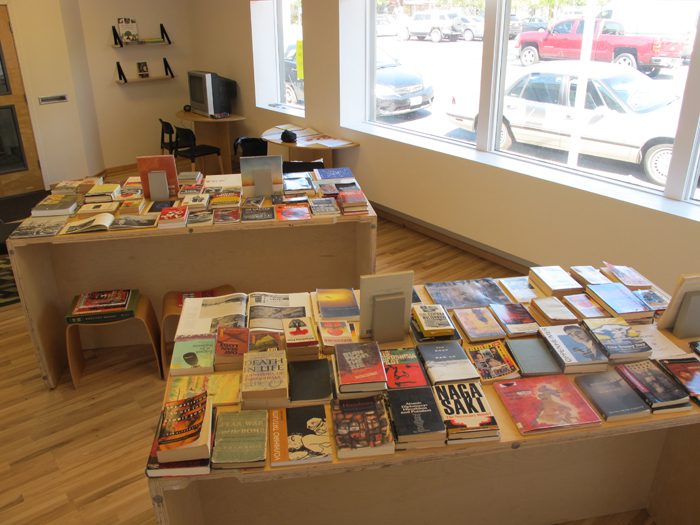

In the most basic sense, the Hiroshima Library is a peripatetic collection of more than 200 books, histories, documents, and hibakusha (a Japanese word that describes Japanese people who were affected by radioactivity and/or atomic bombings) testimonies about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. First installed on a dining room table in an abandoned house in Marfa, Texas, it made a wider debut in 2019 at Bruna, a collaborative press and art space in Bellingham, Washington. In late 2019, it traveled to the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles where it was largely inaccessible due to the pandemic. Its current home is Counterpath in east Denver where it will remain through August 2022.

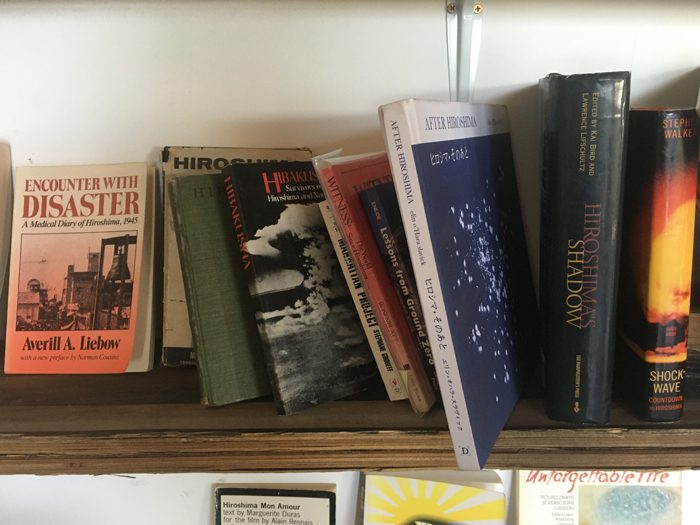

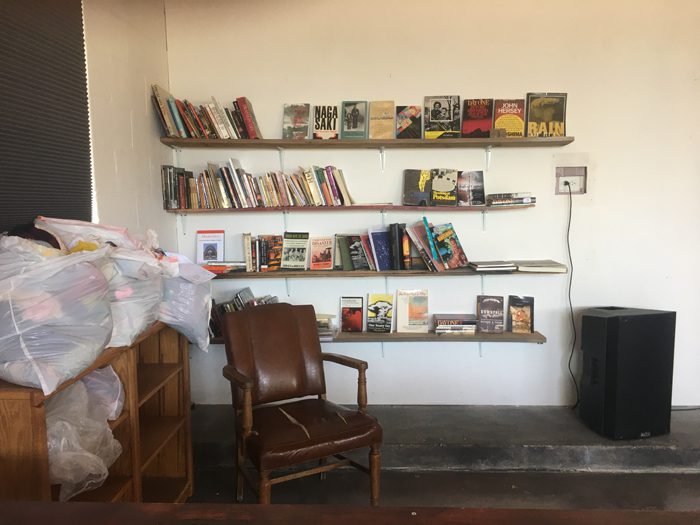

As is the case with all libraries, calling the Hiroshima Library merely a collection of books explains very little. When I visited the library at Counterpath, it was shelved on wooden planks on the back wall of the space. An old leather chair, the kind you might see at a lawyer’s office, sat in front of the shelves. I assumed it was a reading chair, at least that’s what I used it for. The whole set-up is tucked into the corner next to the refrigerators that store the food bank’s perishables—Counterpath, in addition to being an art and community space in an old automotive repair shop, is also a neighborhood food bank.

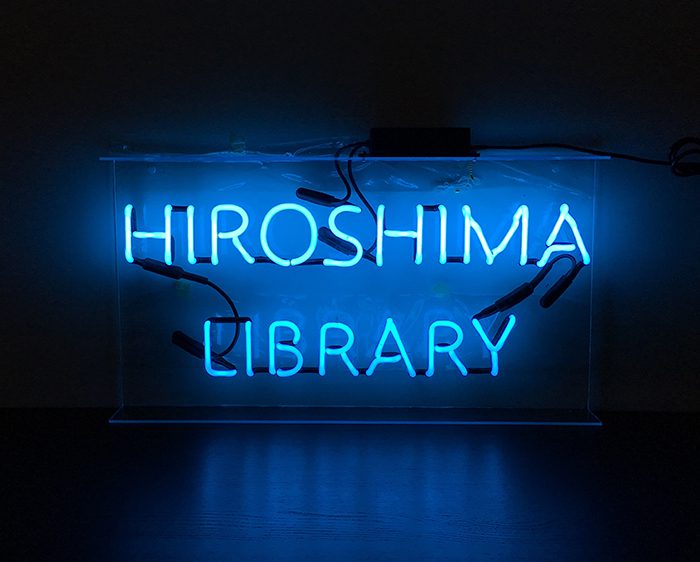

There is no description that accompanies the rows of books. No plaques, no classification system for the items, no spreadsheet, no directions. Shimoda’s name isn’t posted anywhere. The only signal the library is there is a neon sign hanging in the front window glowing blue that reads, “Hiroshima Library.”

For Shimoda, this is a perfect place for the library. “I like imagining the books being in conversation with the fruits and vegetables and canned goods and used books that were already occupying the space. People, too, of course, but organically. Passersby.”

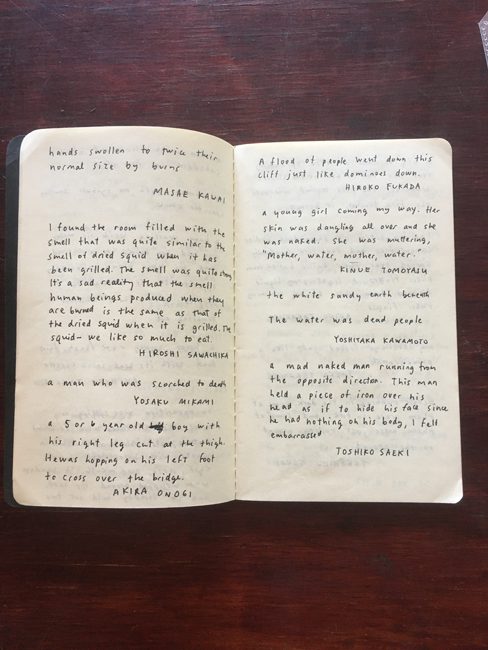

The library is an art installation, reading room, place for contemplation, and collection. The lack of definition or, rather, the abundance of definitions creates disorientation and uncertainty. I perused the shelves, picking up book after book—I’m still not sure if you can check them out. I read the book jackets of some and then reshelved them. With others, I sat down and read a chapter or two. I explored spontaneously. I was led to the next text because of something in me—the cover attracted me, the title. I proceeded this way through books of poetry, photographs, eyewitness accounts, histories written by white American journalists, novels written by famous Japanese authors, love stories, picture books. I gradually realized I was surrounded by humans from all over the world trying to make sense of, explain, justify, describe, process catastrophe and horror. As I kept reaching for books, I wondered what was welling in me, a feeling of repulsion and curiosity, deep, abysmal emptiness, and connection. And all of this brought on by a messy collection of books in an old car repair shop.

Shimoda, a poet, writer, and English professor at Colorado College in Colorado Springs, tells me, “The library sort of started on my tenth birthday” when his parents gave him a copy of, I Saw It: The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima: A Survivor’s True Story. It’s a manga by Keiji Nakazawa and when I visited the library, I Saw It was among the first books, well, that I saw. On the cover is a drawing of a sweaty face with its mouth agape and eyes wide. In the pupils, a blazing yellow mushroom cloud is reflected. The clearly terrified person peers out from some broken wooden planks and it dawns on me that if they’re inside a structure, I’m not. I am outside, unprotected, with my back to the bomb. It is an intense and unsettling cover—and certainly, I’m sure, made one hell of a birthday present.

That same year, Shimoda says that he and his family visited the city of Hiroshima and Peace Memorial Park, a memorial to the victims of the world’s first nuclear attack. And while Shimoda didn’t begin collecting books and stories about Hiroshima and Nagasaki as a child, the experience of visiting the site and the comic book never left him.

Shimoda explains that the Library is inspired by visits to both ground zero memorial sites, but specifically the places built there for relaxation: the Rest House at the Hiroshima site and the Hypocenter Park at Nagasaki where a vendor sells rose water ice cream to over-heated tourists. The inspiration comes specifically from the co-location of refreshment and atrocity—tourists “drinking lemonade surrounded by death.” Other inspirations come from spaces that erase the lines between art space and public space such as Ilya Kabokov’s School No. 6 installation at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas, and the Martha Rosler Library, a collection of the artist’s personal books that wandered from art space to art space from 2005 through 2008.

Shimoda dreams of installing the library in a strip mall next, where it can exist alongside small businesses and people running errands. In a space like this, he writes, “an individual (passerby, tourist, wanderer, child), motivated by an aimless yet open curiosity, might enter and, for a moment, disappear.”

The Hiroshima Library is scheduled to continue through August 2022 at Counterpath, 7935 East 14th Avenue in Denver.