The Distance is Very Frightening

November 1–29, 2019

Cruces Creatives, Las Cruces

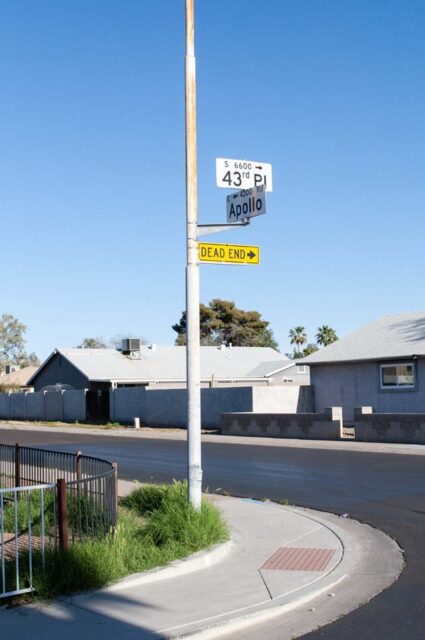

Mónica Martínez-Díaz’s exhibition, The Distance is Very Frightening, opened November 1 at Cruces Creatives in Las Cruces. Martínez-Díaz is a visual artist who uses photography, video, design, and installation to create conceptual work focused on the hyper normalization of violence in Northern Mexican society. This body of work is based on duality and the contradictions she observed growing up in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, her hometown and muse.

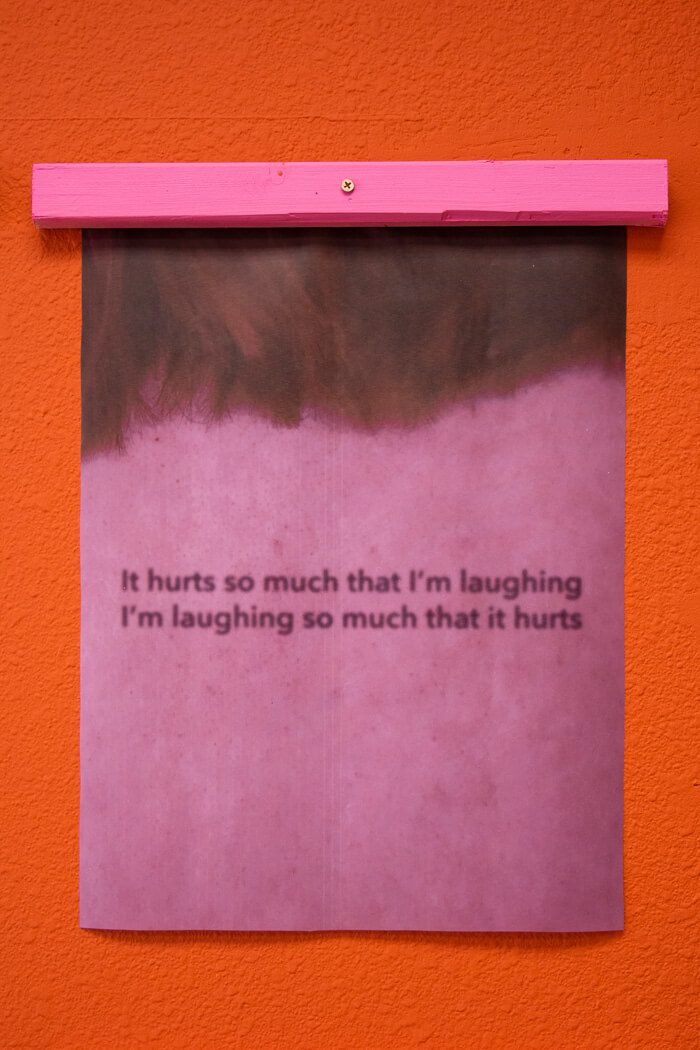

The exhibition unfolds with two opposing colors of red and pink on each wall, holding their own series of photographs printed on maquiladora textiles hanging from a single wood frame banner.

The arms exist in a sea of red, mirroring the other wall and denoting associations with Mexico’s relationship to the color—to passion, to blood.

The photographs in the exhibition are printed on textiles referencing female workers from the maquiladora factories, who make up the greatest percentage of the femicides in Juárez. The frames of the photographs allude to the pink crosses placed around the city to demarcate areas where a victim has been abducted or killed.

On the red wall, the women in Martínez-Diaz’s photographs So tragic, so lucky become anonymous, their backs to us, with sentences that conflate two senses of reality placed on their skin. In one piece are the words “a view without a city and city without a view.” Here, she plays with the incongruity of the city’s rich factory production and the costs at which it comes. We see subjects in rows organized like cemetery markers, waiting for us to inhabit the liminal space. She presents us with two realities of humankind: our propensity for love and connection and our capacity for hatred and cruelty.

On the opposing wall, the textiles of Almost alive are longer and they have curvature as if they are trying to move the solitary arms that inhibit each composition. The arms exist in a sea of red, mirroring the other wall and denoting associations with Mexico’s relationship to the color—to passion, to blood. The sentences are gone in this part of the installation; only inked tattoos remain on the arms that read “always” and “c’est la vie.” The isolated body parts appear in fractured motion, inviting speculation: do they belong to someone dead or living?