1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus

by Charles C. Mann

Vintage Books, 2006

When it comes to the Americas, we here in the northern continent like to believe that, until the arrival of Europeans in the fifteenth century, the land was virginal. A virginal landscape is, of course, ripe for defilement—all those plump, fecund fields are just asking for it.

The problem with this trope is that it is wildly untrue. Mann’s book reveals that, among other facts, the Aztec city of Tenochtitlán was larger, population-wise, than any of its contemporary European capitals. It was also far cleaner, with running water and gardens throughout. Many of these early cities in the New World were thriving long before the Egyptians built their pyramids. Mexico’s pre-contact indigenous farmers had bred a strain of corn that scientists consider “man’s first… feat of genetic engineering.” Finally, by the time the Spanish and English had arrived on its shores, the landscape of the Western Hemisphere was highly cultivated by several advanced civilizations. Take that, conquistadores and pilgrims!

—picked by Kathryn M Davis

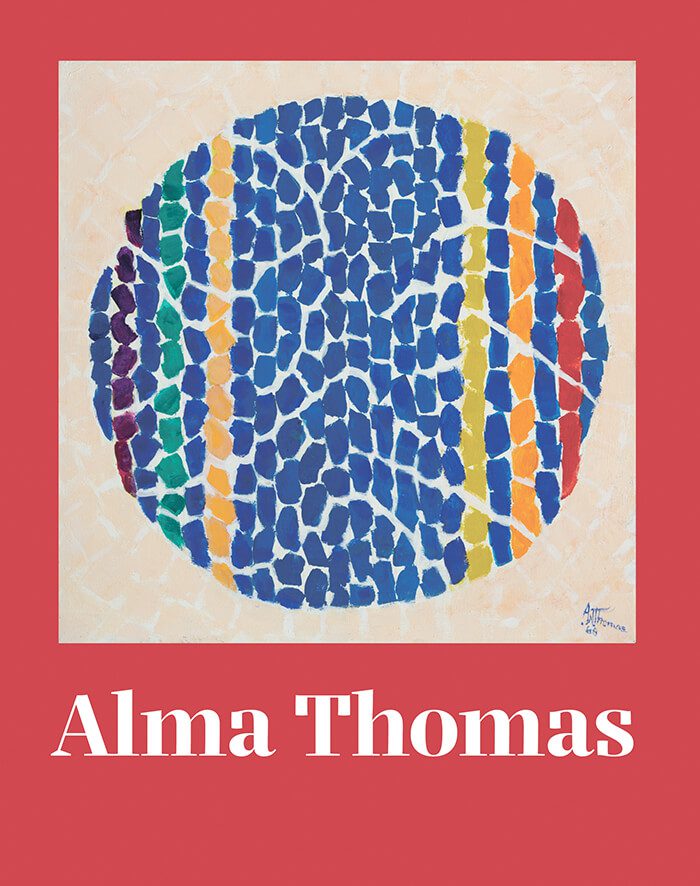

Alma Thomas

Del Monico Books / Prestel, 2016

Alma Thomas (1891-1978) was the first African American woman to be given a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum in 1972. Ever since then her reputation as one of the most pioneering abstract painters of the twentieth century has continued to expand. Early in her career, Thomas was influenced by artists such as Wassily Kandinsky and Loïs Mailou Jones. Also an African American, Jones lived and worked in France and brought back to America ideas culled from the first decades of Parisian Modernism, and the influence of Matisse’s color sense can be seen in Thomas’s own bold and brilliant work. That said, Thomas developed her own unique approach to abstract painting, and her vision of the visceral relationships that colors can create with one another in the space of a painting is powerful, along with the unique style of brushwork that she developed into a kind of transformative visual notation. Thomas used color as a bridge to higher levels of consciousness, her paintings transcending the mundane world of divisions and social discord. This vibrant and comprehensive book is a well-deserved tribute to an artist whose work is timeless and strikingly beautiful.

—picked by Diane Armitage

Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions

by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Knopf, 2017

Sometimes I still wonder what it means to be a feminist. This is quite simply because, for women of color, historically feminist movements have largely been white. I picked up Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s nearly pocket-sized book, Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions, to think about what feminism outside of a “movement” looked like, especially for a black woman living transnationally. Adichie, a MacArthur Grant–winning Nigerian novelist, first wrote Fifteen Suggestions as a letter to a friend who wanted to raise her daughter as a feminist. And because it’s first life was as a personal message, the book is conversational and, at turns, affectionate. That intimacy pulled me in because the suggestions weren’t over-intellectualized or jargony. Instead, they felt grounded and real. She unpacked cultural phenomena like misogyny, gender roles, perceptions of beauty, what she calls “male bluster,” shame, and difference as if they were clothes in a suitcase, pulling out each one and holding it to the light. That familiarity is what makes Fifteen Suggestions feel like a small gift.

—picked by Alicia Inez Guzmán

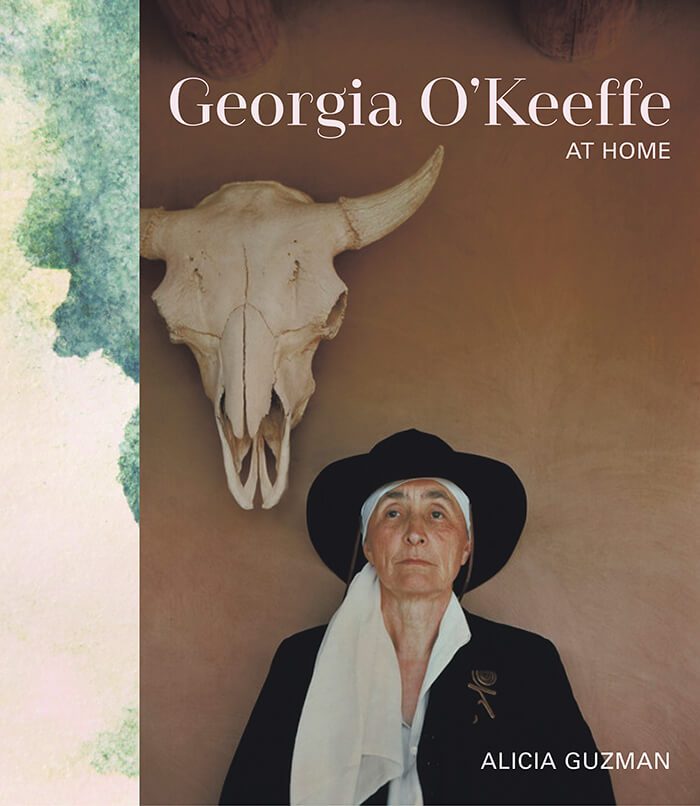

Georgia O’Keeffe at Home

by Alicia Inez Guzmán

Frances Lincoln, 2017

Georgia O’Keeffe’s image as a twentieth-century disruptor—socially, culturally, and even politically—has blurred in the past two decades, particularly among Santa Feans who’ve witnessed the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum’s tender but staid exhibition program. Enter Alicia Inez Guzmán, whose new biography of O’Keeffe is disguised as a coffee table book but shouts like a new manifesto for a woman who ought to be revived as a symbol of Trump-era resistance. Each chapter begins with a defiant quote from O’Keeffe and dives into one of the many places she lived. Through descriptions of O’Keeffe’s paintings and little-told stories from her life, Guzmán examines the modernist painter’s movements through Wisconsin, Virginia, Texas, New York, Illinois, and, of course, New Mexico. “Where I have been and how I have lived is unimportant,” reads a quote from the artist in the book’s introduction. “It is what I have done with where I have been that should be of interest.” This biography proves that O’Keeffe shaped place and culture as much as it impacted her, offering a hopeful example of artistic agency in our tempestuous moment.

—picked by Jordan Eddy

Irving Penn: Centennial

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017

Penn believed that photography was the art form of his generation, “the present state of man’s visual history.” Throughout his sixty-year career he created portraits of the cultural elite, indigenous peoples, and unknown workers, along with still life, nudes, and fashion photography. He was a consummate technician, producing elegant gelatin silver and platinum prints, and also experimented in color separation and fine book printing. This comprehensive large-format volume catalogues the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s eponymous international retrospective exhibition (April 24-July 30, 2017). Penn’s signature style places his subjects against a seamless backdrop to emphasize their sculptural presence, initially for Vogue magazine. It was as successful a strategy in his photographs of icons like Pablo Picasso; subjects from Benin, New Guinea, and Morocco; diverse still lifes, from fragile flowers to gritty cigarette butts, or meticulously placed household objects. The book is filled with exquisitely printed quadratone images, using black and three other inks on Italian paper. The essays chronologically highlight all significant aspects of Irving Penn’s work, including origins, cultural significance, and related influences. The book stands as a tribute to a highly creative artist whose broader portfolio holds an important place in photographic history.

—picked by Jackie M

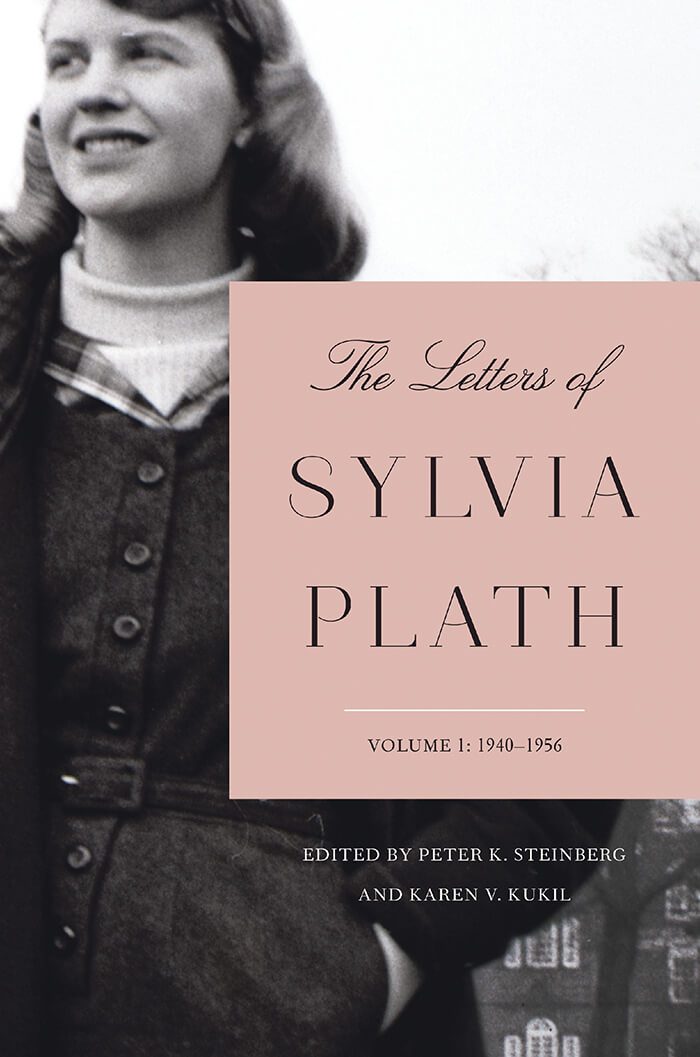

The Letters of Sylvia Plath Volume 1: 1940-1956

edited by Peter K. Steinberg and Karen V. Kukil

Harper, 2017

With the publication of her letters, Sylvia Plath finally has the chance to tell us her life in her own words, after a fifty-three-year stranglehold on the poet’s papers by her late sister-in-law Olwyn Hughes. Because she wrote so many letters, this first volume clocks in at nearly 1400 pages, spanning 1940-1956, from childhood through college and her early career. This, her postmortem autobiography, is insanely, thrillingly complete. We see her at age eight, with ink-stained fingers, drawing a self-portrait of her and her Aunt Dot flying through the air. We read dutiful reports to mother from summer camp and school. And, perhaps most crucially, we see her in the earliest moments of her writing life, desperate both for companionship and validation of her work. At this point, in walks Ted Hughes. The complexity of her relationships with her mother, with Ted (whose abuse of Sylvia has been long-denied by the estate, although evidence elsewhere has all but confirmed it), and with herself will keep a reader puzzling and satisfied for at least the next year—at which point we can devour the conclusion in Volume II.

—picked by Jenn Shapland

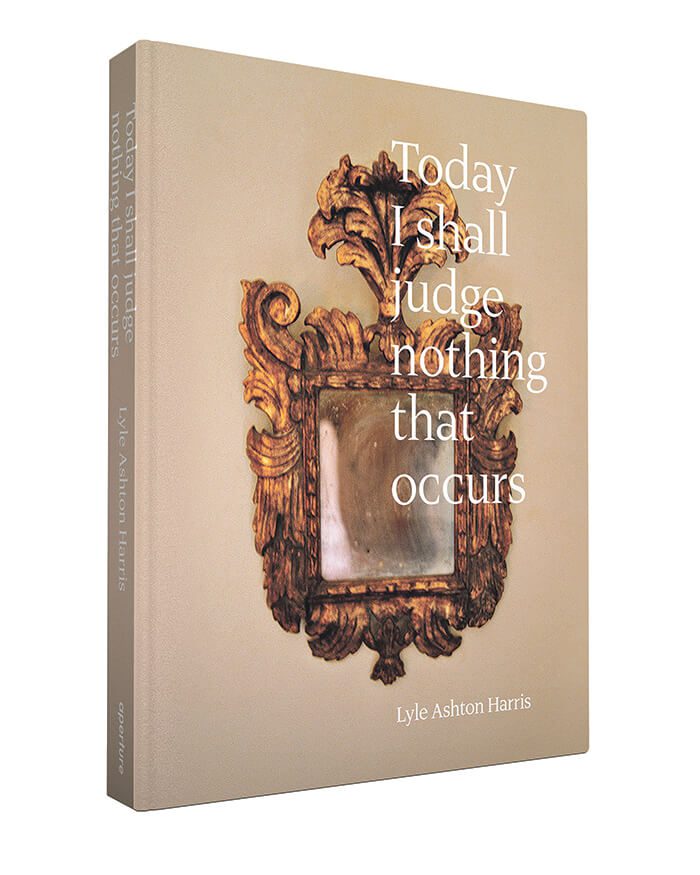

Lyle Ashton Harris: Today I Shall Judge Nothing That Occurs

edited by Johanna Burton

Aperture, 2017

Between 1988 and 2001, Lyle Ashton Harris was living at the intersection of several culturally potent historical moments, significantly the AIDS crisis and the advent of an intellectual turn toward the politics of identity. Harris, who is a black gay man and whose stomping grounds spanned academic conferences and the drag shows of Harlem, took thousands of slide photos of his friends and their activities during those years—a body of work he now refers to as his Ektachrome Archive. Today I Shall Judge Nothing That Occurs features a selection from that archive alongside images of another archive: Harris’s journals, which contain notes, longer diary entries, Polaroids, and clippings ranging from art reviews to ads for hustlers. Sixteen written contributions by artists, critics, and scholars, some of whom were contemporaries of Harris and others whose own practices were affected by his, round out the book. Within, images of luminaries such as bell hooks, Rashid Johnson, and Vaginal Davis juxtapose texts by Marlon Riggs, Mickalene Thomas, and Catherine Lord, among many others.

—picked by Chelsea Weathers

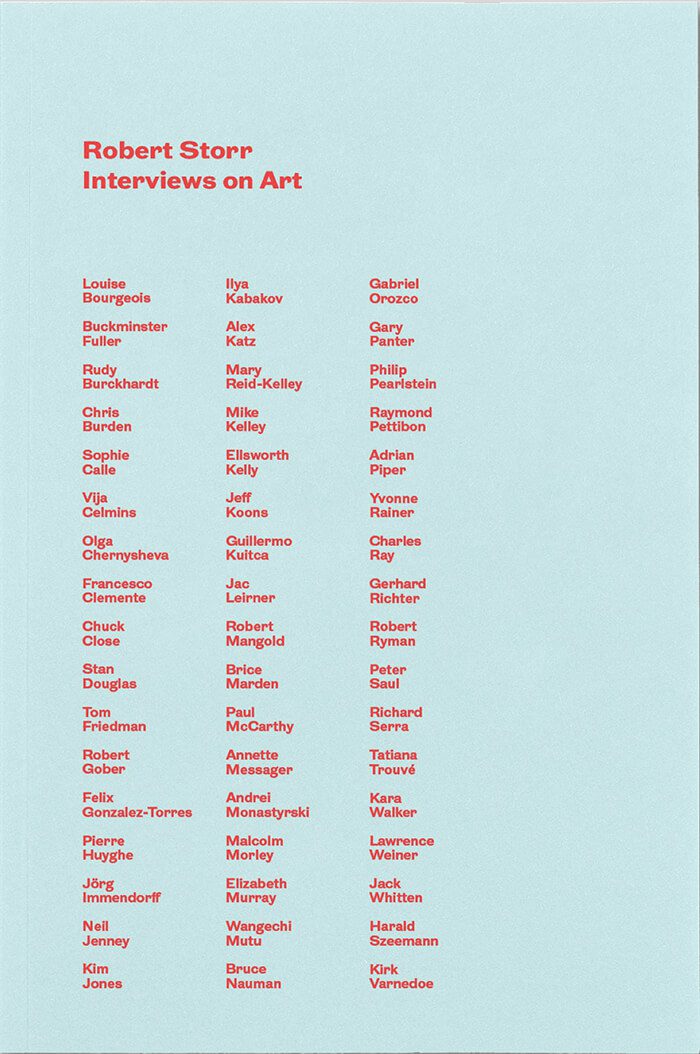

Robert Storr: Interviews on Art

edited by Francesca Pietropaolo

HENI Publishing, 2017

Robert Storr—critic, curator (Museum of Modern Art, 1990-2002), and artist himself—long operated outside of the art-world establishment in his early career, and his status as a free agent created trust and intimacy between himself and his interviewees. This anthology presents sixty-one dialogues with artists and curators from 1981 to 2016, some published here for the first time. The interviews span generations, media, and different aesthetic and conceptual inclinations, providing insights into the thinking, methods, achievements, and trajectories of some of the most influential artists of our time, including names such as Louise Bourgeois, Buckminster Fuller, Mike Kelly, Gerhard Richter, Wangechi Mutu, Kara Walker, Ilya Kabakov, Chuck Close, and many more.

One of the most compelling interviews in the collection is that of the volume’s editor, Francesca Pietropaolo, interviewing Storr on his interviewing methodology and experiences. In it, Storr contemplates the format of the interview dialogue as a mode of inquiry and art writing, one in which, importantly, the resulting text is a process of discovery, in which two people open and pursue questions for the reader but do not land on a monolithic or didactic view, allowing for multiple narratives and interpretations.

—picked by Lauren Tresp

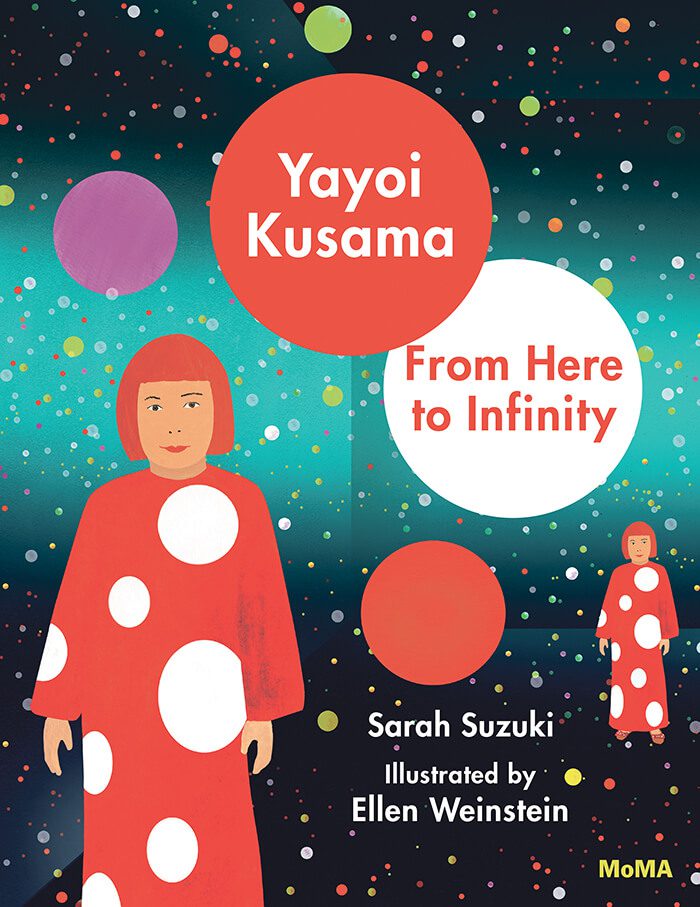

Yayoi Kusama: From Here to Infinity

by Sarah Suzuki / illustrated by Ellen Weinstein

Museum of Modern Art Press, 2017

How often does a contemporary artist reach such international celebrity that her shows sell out wherever she goes and her name is readily recognized from galleries to coffee shops, eliciting excitement at every mention? For Yayoi Kusama, that celebrity is not only deserved but a long time coming. In 2017 there was perhaps no other artist that achieved such star status. Sarah Suzuki’s children’s book presents Kusama’s career and the origins of her work most accessibly—evincing her worldview, the contexts in which she works, and her singular devotion to her craft through short doses of text and the evocative illustrations by Ellen Weinstein. Given that Kusama’s childhood visions have long been a wellspring for her art, this twenty-six-page book for young readers is a perfect medium for telling the artist’s story and does so to touching effect. Created in collaboration with Kusama’s studio in Japan, From Here to Infinity is a primer on the prolific artist and well worth a quick read for newcomers to her work or longtime fans who crave a refreshingly straightforward take on her history, inspirations, and body of work. For readers of any age, the book is a wild success.

—picked by Maggie Grimason