Each year, The Magazine curates a list of the year’s best art books.

This year we’ve asked our contributors for their recent favorite arts reading materials. The results ranged from exhibition catalogues to memoirs, artist books to artists’ writings.

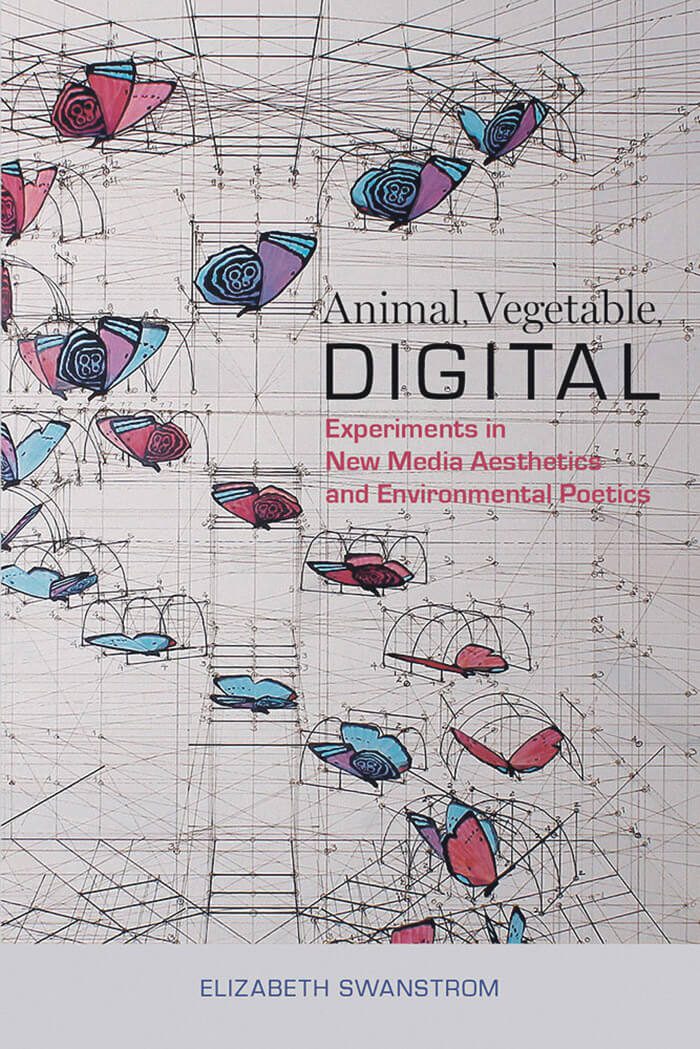

Animal, Vegetable, Digital: Experiments in New Media Aesthetics and Environmental Poetics by Elizabeth Swanstrom

University of Alabama Press, 2016

Straight outta Tuscaloosa comes the winner of the Elizabeth Agee prize in American Literature. Animal, Vegetable, Digital: Experiments in New Media Aesthetics and Environmental Poetics by Elizabeth Swanstrom makes a persuasive argument for the organic art energy of the digital as a driving force for environmental politics, as the breakdown between the classical distinctions between our bodies, minds, technologies, and the natural continues unabated. Her intelligent and highly readable text moves nimbly between classical precedents and cutting-edge new-media experiments. She compares, for example, Shelley’s ode to Mont Blanc, in which the spirit of the mountain is a moral force, to sound artist Kalle Laar’s Call a Glacier project that puts callers worldwide in direct contact with the real-time sounds of the Vernagtferner Glacier, “speaking” its precipitous decline in the face of global warming. This is just the tip of the iceberg, Swanstrom puns. A must-read for new mediators and planet protectors alike.

—Jon Carver

Before Pictures by Douglas Crimp

University of Chicago Press, 2016

On September 24, 1977, art critic Douglas Crimp curated Pictures, an exhibition staged at Artists’ Space in New York City. Simply titled, Pictures heralded the advent of postmodernism. The exhibition’s opening, and its critical reception in the art world, serves as a bookend to Crimp’s reminiscences about life in the economically derelict but creatively thriving New York City of the late 1960s and 1970s. In Before Pictures, Crimp refracts a spectrum of cultural and art history through profoundly personal stories about life as a queer man living in a city that invited experimentation. Throughout, he candidly and eloquently interweaves professional experiences, from his time as assistant curator at the Guggenheim to his role as the managing editor of October, with intimate ones, including love affairs, disco jaunts, cruising, and drug use. In Crimp’s eyes, to live and work in New York was to carve out a space of one’s own, for “being queer is a matter of a world you can inhabit, not something you simply are.”

—Alicia Inez Guzmán

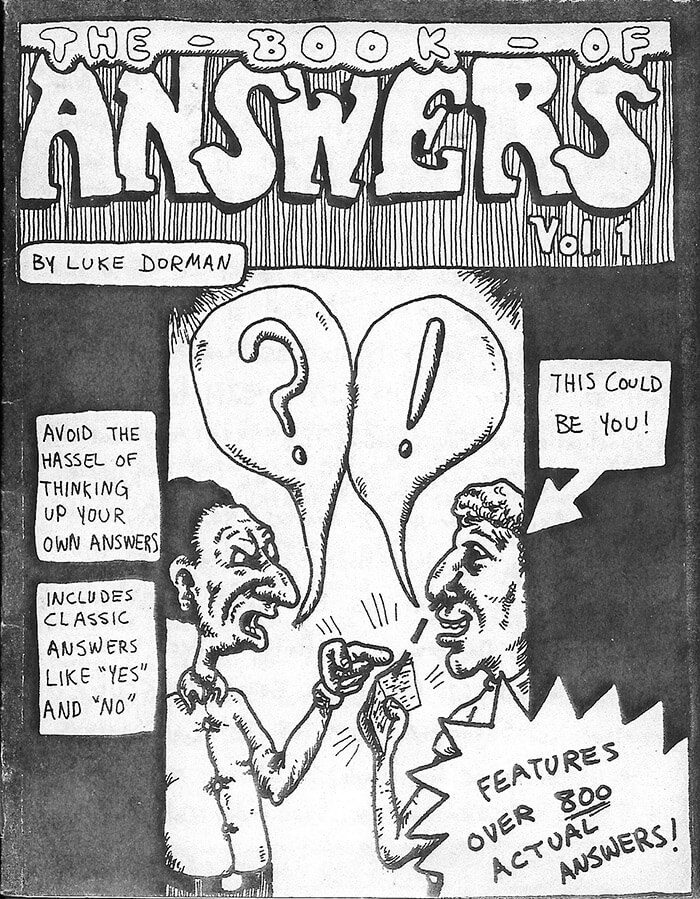

The Book of Answers, Vol. 1 by Luke Dorman

I’m often asked how is it I know so much and why I have so many valuable answers to life’s most elusive questions. For many years I have selfishly kept the reason a secret, but as time moves forward and my answering days become fewer, I realized it’s time to divulge my source. The Book of Answers, Vol. 1 (c. 2001-02) by Luke Dorman is one of the most valuable resources of factual information that has ever been published to date. Before “asking the Cyber” for answers became popular, this book dominated the world of knowledge, superseding the encyclopedia, the dictionary, and even the Good Book. The Book of Answers is so chock-full of usable answers, it’s like a Magic 8 Ball in the fifth dimension. Classic answers include “Yes” and “No.” For more complex questions, there are answers like “Probably,” “Salami,” or “Until I Die.” I owe this little book my collegiate success, and I’ve dominated every test I have encountered since I picked it up. Stephen Hawking, eat your heart out.

—Clayton Porter

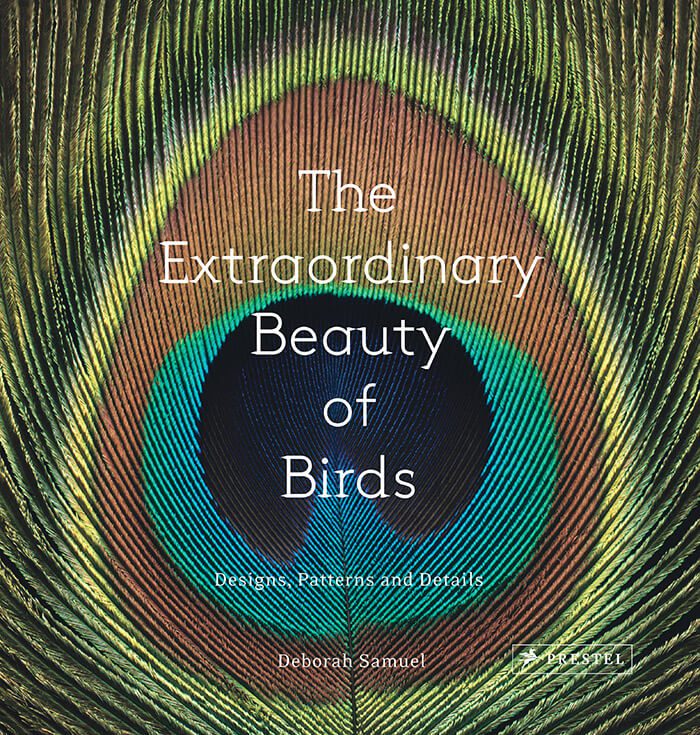

The Extraordinary Beauty of Birds: Designs, Patterns and Details, photos by Deborah Samuels, text by Mark Peck

Prestel, 2016

We are accustomed to seeing representations of nature mediated through the hand of man in books and museums, yet natural elements can stand alone as pure representations of art. The intimate photographs in The Extraordinary Beauty of Birds: Designs, Patterns and Details offer eloquent examples from the avian world. The photographer Deborah Samuels states that the images in this book are a meditation on what it means to be alive and also serve as “portraits” of abstract ideas. The images were photographed from specimens in the Royal Ontario Museum’s ornithology collection and include details of feathers, eggs, nests, and skeletons shot against a black background, which accentuates the elegance of the forms and the brilliance of the colors. Attributions and brief descriptions of the objects are provided. This volume will please the forty-eight million birders and may attract others to bird watching, if not in the field, then through the gifted eye of this photographer.

—Jackie M

Float by Anne Carson

Alfred Knopf, 2016

“A collection of twenty-two chapbooks whose order is unfixed and whose topics are various./ Reading can be freefall.” So says the back cover of Float. While the concept of freefalling into these short pieces—some as brief as a single page—held the allure of fitting nicely into a busy person’s schedule, in practice I become consumed by pulling out each piece from Carson’s collection and sinking my brain into them with abandon.

In “Contempts: A Study of Profit and Nonprofit in Homer, Moravia and Godard,” Carson meditates on the exchange of goods/gifts and the boundlessness of Woman in Homer’s Odyssey, Alberto Moravia’s Il Desprezzo (1954), and Jean-Luc Godard’s film Le Mépris (1963), all while straddling Classical, literary, and film discourses with ease. In “Merry Christmas from Hegel,” Carson combats personal holiday despair through an enactment of Hegel’s philosophic Speculation by “snow standing” in a fir tree forest. Throughout, the collection disrupts and melds the structures of memoir, poetry, academic writing, and prose, and spans time, voice, and structure, much like Carson herself defies easy categorization.

—Lauren Tresp

Frantumaglia by Elena Ferrante

Europe, 2016

Elena Ferrante wants you to know who she is. You may have heard otherwise: journalists outing her against her will, her consistent refusal to speak in public. But in her most recent U.S. publication, an expanded translation of Frantumaglia, the writer behind Ferrante’s works sheds light on the difficulty of maintaining a pseudonym in the age of social media and rabid celebrity.

The collection brings together letters between Ferrante and her publisher, Sandra Ozzola, and texts of the few written interviews she has given in a meditation on the purpose of writing and the role of the author. Much more revealing than a face or a name, Frantumaglia expands Ferrante’s fiction to the author herself. Ferrante readers can rejoice: this is actually a new novel, the novel of the author, in which Ferrante pursues “the same effect as literature, that is, to orchestrate lies that always tell, strictly, the truth.”

—Jenn Shapland

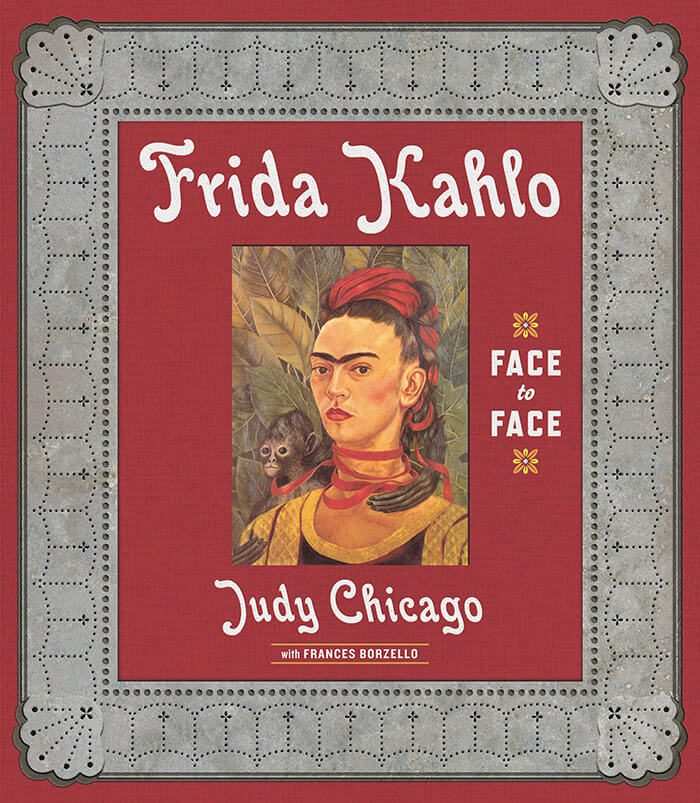

Frida Kahlo: Face to Face by Judy Chicago with Frances Borzello

Prestel, 2010

This is one hell of a gorgeous book, lush from its elaborate cover to its impeccably reproduced images. Still, questions loom: why would Judy Chicago want to take time out of her crazy-busy schedule to write a book about something other than her own numerous projects? Aren’t we all kind of over Kahlo, anyway, having read the 1983 Hayden Herrera bio and seen the movie? You may think so. Get your hands on this book and you’ll change your cynical ways.

The chief accomplishment of this book is to raise our understanding of Kahlo, past the exceptionalism of her biography into the universality of her art. For Chicago’s fans who are familiar with her deep research into the history of women in art and its profound significance to Second-Wave Feminism, there lies this fact: in the 1970s, when Chicago was making her iconic Dinner Party and Herrera was working to dislodge Kahlo from behind her famous husband’s monumental shadow, there was no history of women in art. Take that, post-Feminists.

—Kathryn M Davis

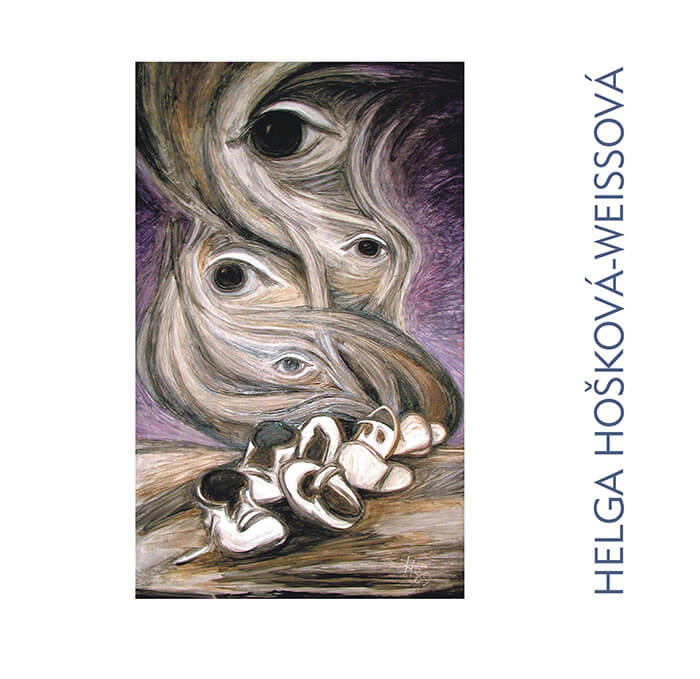

Helga Hošková-Weissová: Exhibition for the Artist’s 80th Birthday by Arno Parík

Jewish Museum in Prague, 2009

New to my personal library in 2016 was Helga Hošková-Weissová: Exhibition for the Artist’s 80th Birthday (Jewish Museum in Prague) by Arno Parík. I was researching Hošková-Weissová for a book project, and this lavishly illustrated yet slim volume offered more about her life and art than any other resource I consulted. A Czech Anne Frank who peppered her World War II diary with stark illustrations, Hošková-Weissová survived four concentration camps and documented the horror in words and pictures as she cheated death multiple times and even considered suicide to stop the agony. After liberation, her art exploded from childlike ink and watercolor pictures of transport trains departing Terezín for Auschwitz to summer-colored oil paintings of Israeli streets to Holocaust memorial plaques. The catalogue traces Hošková-Weissová’s artistic development under her teacher, early Cubist painter Emil Filla, and leads us through her evolution into large-scale, modernist mixed-media pieces. She continues to paint in her Prague apartment.

—Susan Wider

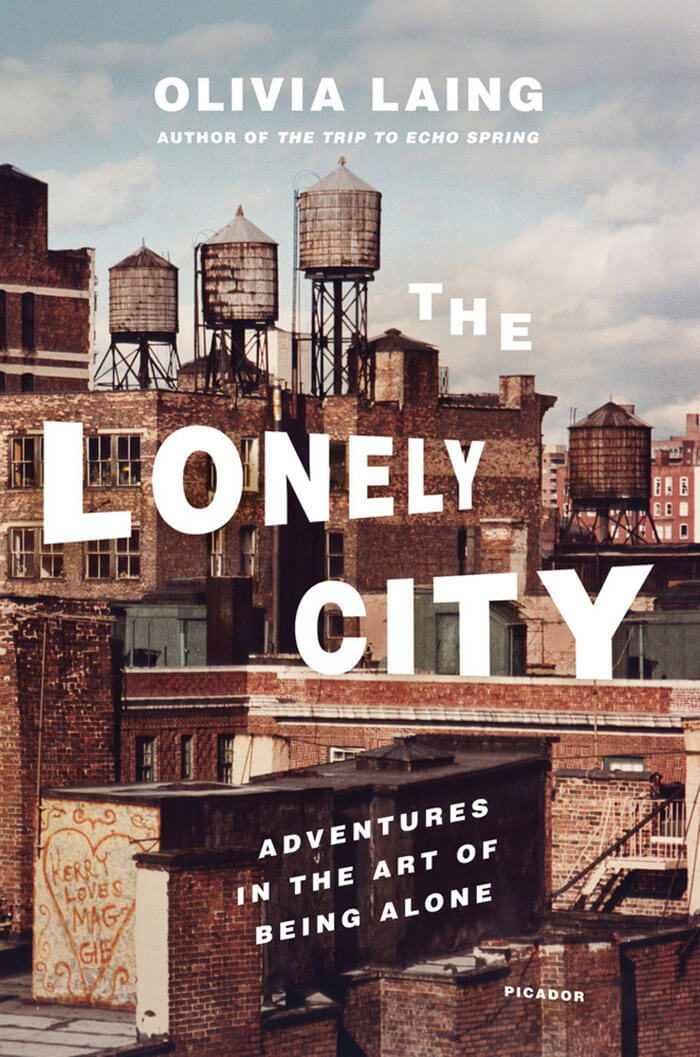

The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone by Olivia Laing

Picador, 2016

British writer Olivia Laing moved from London to New York City for love but soon found herself alone and adrift in a metropolis of strangers. This sets the stage for a detective story of sorts, as Laing hunts down the historic hiding places of several legendary, lonely city dwellers. On long strolls across Manhattan—and on spelunking expeditions into the shadowy archives that make up its hippocampus—she encounters the ghosts of artists Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, and David Wojnarowicz. As Laing descends deeper into psychological isolation, she travels to Chicago to devour the diaries of the prolific shut-in Henry Darger and trawls the Internet for pixelated remnants of singer Klaus Nomi and early digital provocateur Josh Harris. The stomping grounds of these disparate figures begin to overlap, as do the conceptual territories of their solitary artistic explorations. Laing embeds a mosaic of biographies within her memoir and emerges as a pioneer of a decidedly contemporary strain of art history scholarship.

—Jordan Eddy

Made in L.A. 2016: a, the, though, only

Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

DelMonico Books

The Hammer Museum catalogue for Made in L.A. 2016: a, the, though, only represents a survey of twenty-six artists, and is the latest iteration of art produced in Los Angeles and featured at the Hammer. Although the artists may live in L.A. now, they come from all over—Lebanon, New York, Mississippi, Spain, Geneva—and their conceptual projects reflect the ambiguous nature of the subtitle of the book. All the work in this book is open-ended in its investigations, making it hard to neatly sum up any one given work. One fascinating installation, Reconstructed Southwest Artifact by Gala Parras-Kim from Colombia, focused on Anasazi shards that she found for sale on eBay. Parras-Kim employed techniques of archeological research for cataloguing and methods of typology, opening up a space to work with ideas about conservation and preservation in a world where everyone’s culture is for sale. There is a provocative spectrum of themes investigated in this book and they often relate to the many oblique narratives about L.A. as a place where there are many possibilities for experimental work that isn’t always supported by art’s mainstream commercial juggernaut.

—Diane Armitage

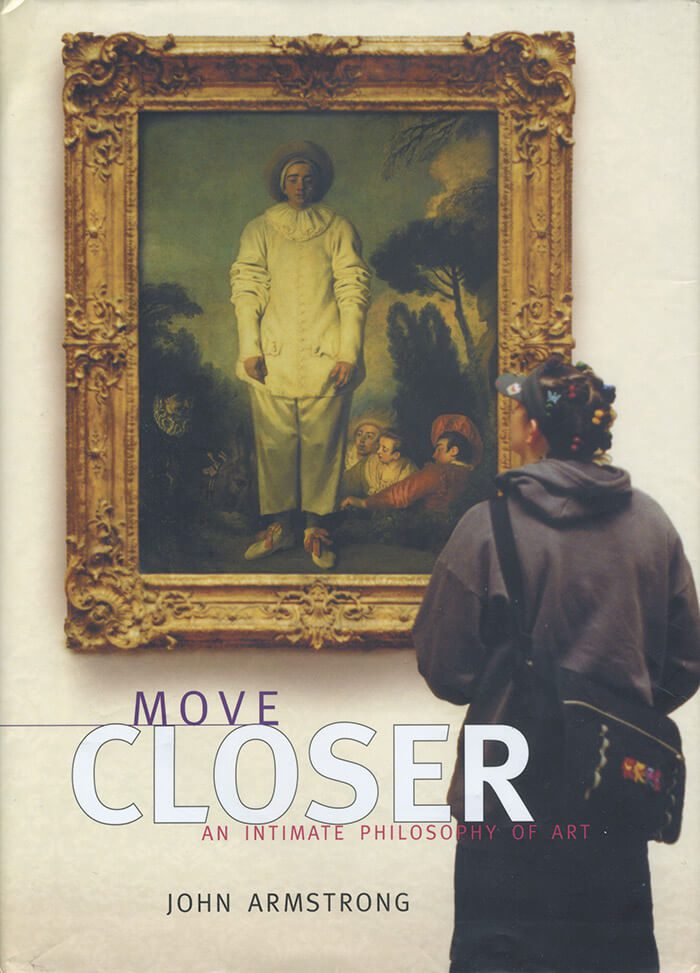

Move Closer: An Intimate Philosophy of Art by John Armstrong

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001

“What good we get from art depends upon the quality of our visual engagement with particular works,” writes John Armstrong in Move Closer: An Intimate Philosophy of Art. While there are many resources that address how to look at art, Move Closer focuses on the significance of our personal responses to art and the richness afforded by tapping into our own histories of “impassioned looking.” Especially refreshing are the chapters “Information” and “Resources,” which suggest that facts alone don’t necessarily illuminate artworks and that everyone inherently possesses the tools required to effectively engage with art.

While Move Closer does have some esoteric and meandering moments, overall it’s an accessible and insightful read that considers how and why we derive pleasure from viewing art through a personal lens. A valuable resource for anyone who mediates art and art audiences and an encouraging treatise for the art enthusiast.

—Elaine Ritchel

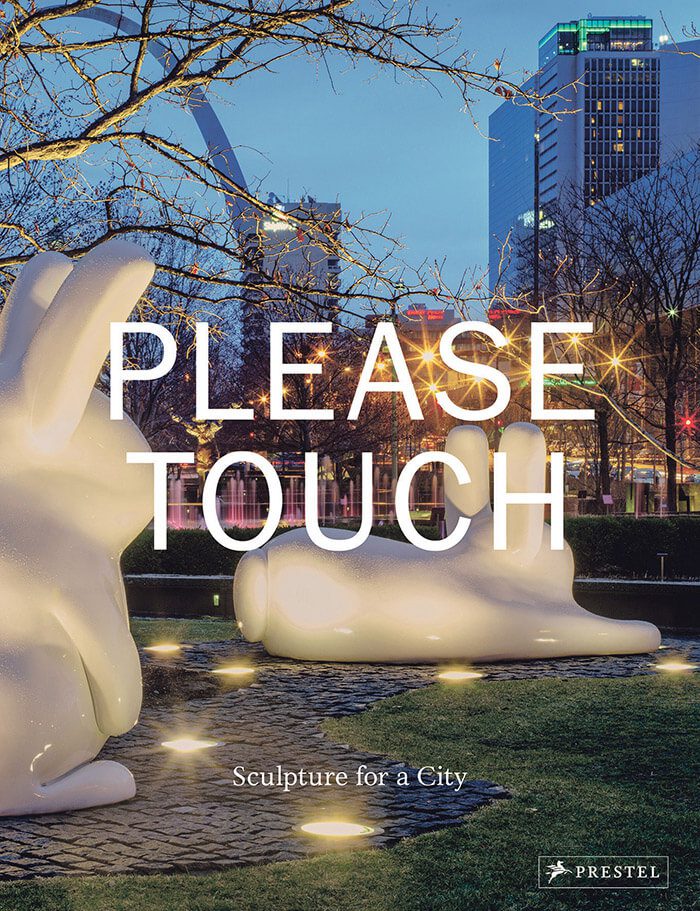

Please Touch: Sculpture for a City by Warren Byrd, Robert Duffy, Paul Ha, Peter MacKeith, Patricia C. Phillips

Prestel, 2016

“Please Touch” is something you don’t often hear in art museums. But it’s the title of a lovely new book on public art from Prestel. Please Touch: Sculpture for a City is a dazzling compendium of public artworks in and around St. Louis, Missouri, especially those sponsored by the Gateway Foundation. There are multiple color photographs of the pieces (whether whimsical, complex, classic, or minimal) sited throughout the city, in particular the ambitious Citygarden project. Five scholars offer engaging discussions, and a detailed map indicates where all the works are located—including an area called Ferguson, in the news most recently for urban unrest. This book inspires hope. Focusing on the relationships between place, sculpture, and people, it offers many images of crowds that we would have to call “racially integrated” enjoying public space. Please Touch makes a strong case for the enriching, even joyous influence of art in public places.

—Marina La Palma

Reductionism In Art And Brain Science by Eric R. Kandel

Columbia University Press, 2016

People wonder about contemporary art. They can’t figure out what it means or why it costs so much. The question of meaning is related to the question of value. When you look at a work of art and can’t understand it, you ask yourself, “What does it mean?” Asking that question—the most human of all questions—forces you to pay attention, not just to the work of art but to everything else you don’t understand. In Reductionism In Art And Brain Science, neuroscientist and Nobel Prize winner Eric Kandel unlocks the vault of the brain and guides you through the treasures of the mind. If your brain has a taste for questions it can’t answer, your mind will thank you for reading this book.

—Joshua Baer

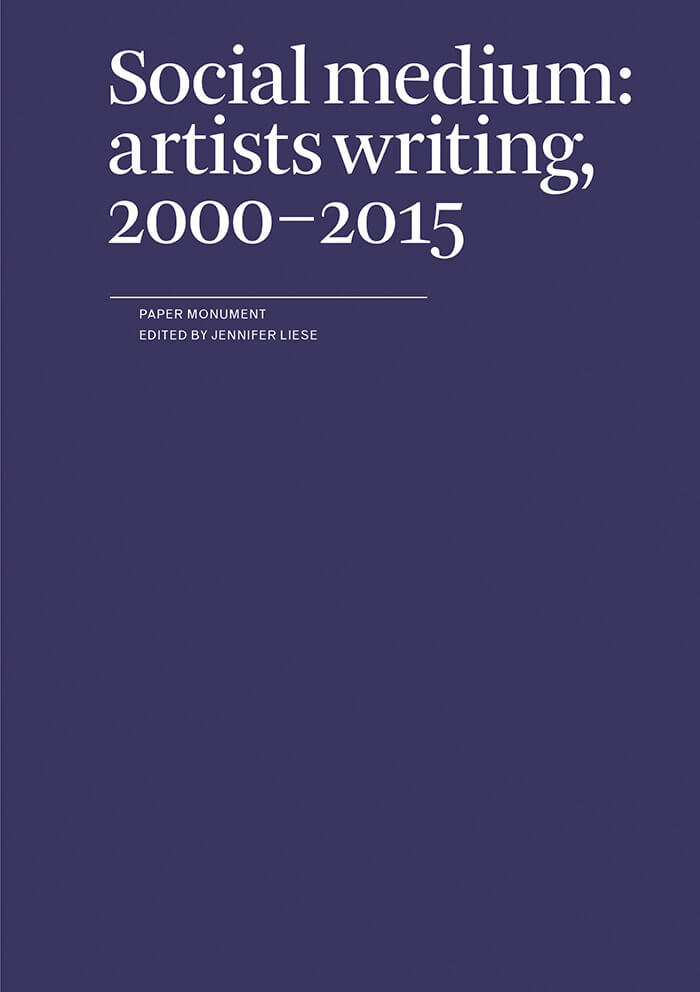

Social Medium: Artists Writing, 2000–2015 edited by Jennifer Lies

Paper Monument / n+1 Foundation, 2016

Artists’ writings proliferate the twenty-first century in an unprecedented quantity. This, according to Social Medium’s editor Jennifer Liese, is mainly due to two factors: the Internet (of course) and the focus of developing artists’ writing skills in BFA and MFA programs. Social Medium gathers seventy-five writings by artists into a beautifully printed anthology and divides them into five categories, including “Artists Writing on Art,” “Artists Writing on Their Own Art,” and “Artists Writing About the World.” These categories are sensible, but once you delve into the writings themselves, they become irrelevant. Each piece, culled from magazines, blogs, and small-press publications, is distinctive more for the artists/writers’ voices and the intelligence and inventiveness of their contributions. Favorites include Adam Pendleton’s poem/script/manifesto “Black Dada,” Emily Jacir’s diaristic “Some things I probably should not say and some things I should have said,” and Ryan Trecartin’s graphically hilarious “Excerpt from the Transcript of The Re’Search (Re’Search Waits).”

—Chelsea Weathers

Stuart Davis: In Full Swing

DelMonico Books, Prestel 2016

It’s not a coincidence that Arshile Gorky’s admiration of Davis was the link between the first American Modernists and the postwar New York School and all that jazz—an intentional nod to Davis as one of the first artists to “dig it,” this distinctly American idiom. Davis is for the post–Ashcan School what Gorky became for the New York School—an avatar for one of the two great waves of American modernism. Stuart Davis: In Full Swing traces that trajectory with beautiful color images of his work and two solid essays by Whitney and National Gallery curators, respectively, Barbara Haskell and Harry Cooper. Stuart Davis was arguably the only American painter in the early decades of the twentieth century who “got” Cubism from the 1920s. By the 1940s his painting would secure for the next generation his “double legacy” as “a precursor of both pop art and contemporary abstraction” (book jacket). In Full Swing gives full and rich narrative to an achievement that Barbara Rose concisely described in 1975, evoking the effect of jazz itself: with their syncopated rhythms, elegant tension, and nervous energy, his paintings “express Davis’ concern with ordering the frenzy he found in the American scene.”

—Richard Tobin