At Southwest Contemporary, we’ve been taking note of the way the art world is reacting to and participating in the global protests and conversations after the death of George Floyd while in police custody on May 25, viewing, listening, and compiling meaningful commentary, actions, and art.

As a small, local arts media company, we believe that engaging with the arts helps cultivate empathy, think critically about complex issues, and creates space to listen to one another more deeply and compassionately. We commit to continually aligning our efforts with the communities, organizations, and voices working towards meaningful, long-term solutions to end racism. We commit to amplifying marginalized voices, and know we have more work to do to bring greater diversity and inclusion into our publishing.

While we are currently operating at a greatly reduced capacity due to pandemic-related losses, we do have a platform on which we can share voices with something very important to say. Here, we’ve compiled a collection of distinctive articles we consider essential reading.

The Art of Social Distance in the Era of #BlackLivesMatter, ArtReview (June 10, 2020)

Richard Hylton writes about social distancing in America as a well-established practice of maintaining distance between realities in housing, education, and the judicial system, depending on your race. How can this moment, he writes, bring critical and meaningful change, as opposed to simply talking about change?

“Whatever unfolds in the coming weeks, months and years in the US, the challenge for galleries and other institutions will be how they can be true to their words and continue to push back deep-seated racism be it inside or outside the institution. However presently, as much as it is a time for action and vocality, and as counter-intuitive as it might seem, ratcheting up equality policies, scrambling to diversify trustees and staffing will miss the point. More critical reflection and less tokenism is needed. As current events graphically illustrate, from the Civil Rights Act onwards, decades of laws, policies and initiatives have not only failed to diminish racial inequity but have normalised it in everyday life. At a time riven with uncertainty, when coronavirus and protests against police brutality have challenged conceptions of normality, art institutions must also more fully consider the real implications of a ‘new normal’ in an era of Black Lives Matter.”

Floyd Case Forces Arts Groups to Enter the Fray, The New York Times (June 7, 2020)

Now in their fourth week, protests online and in-person have put pressure on arts organizations to admit wrongdoings and commit to change. This New York Times article provides a good round-up of what art institutions are doing, and the reactions they’ve garnered.

Why Colston Had to Fall, ArtReview (June 9, 2020)

In America and abroad, statues that venerate violent and racist historical figures are being taken down, either by way of protesters or mounting pressure put upon officials. A piece in ArtReview by Dan Hicks, a professor of archeology at University of Oxford, describes why removing these statues is essential to the toppling of racism itself.

“As the scholar Nicholas Mirzoeff has observed, these statues were never “just statues”, but part of an apparatus of racism. Statues were used to make racial violence persist. Today, their physical removal is part of dismantling systems of oppression.”

“Calls for action are not about iconoclasm, but about ridding our cities of the enduring infrastructures of white supremacy, tracking and tracing a disease that attacks the ability to breathe.”

Dread Scott on Confronting Racial Oppression in America, Art in America (June 10, 2020)

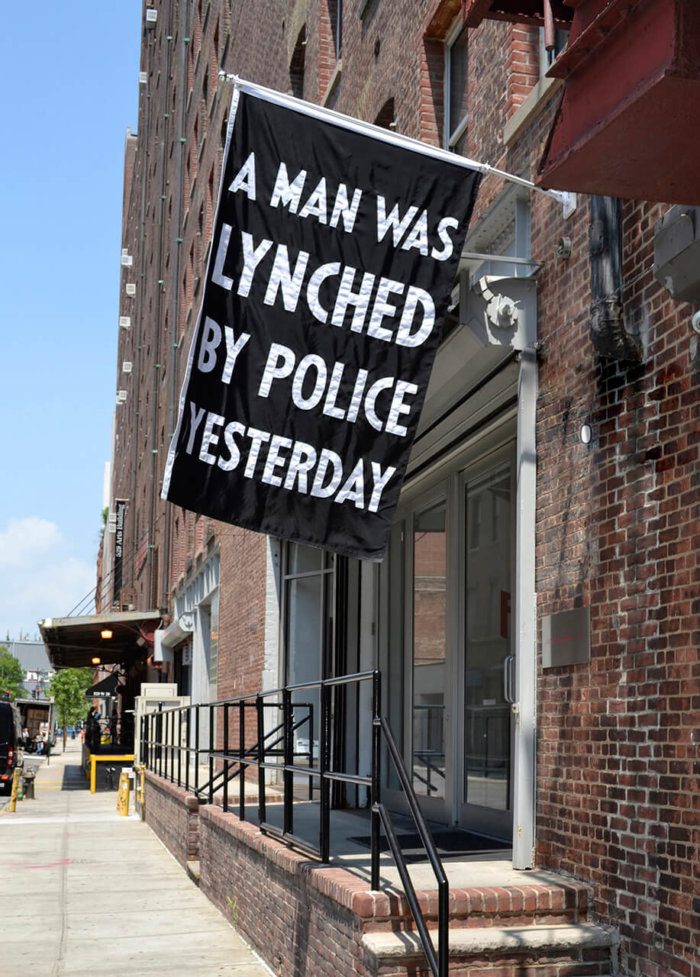

Artist Dread Scott’s 1989 work What is the Proper Way to Display a US Flag propelled conversations about oppression represented in the American flag, and eventually involved him in the 1990 Supreme Court Decision US v. Eichman. In an article published in Art in America, Scott writes of the prominence of racism in art today.

“Lynching images are also present in the work of artists Hale Woodruff, Isamu Noguchi, and Diego Rivera. It’s important to look at these images. If you don’t know that this is how the police routinely treat Black people, you need to look. You need to hear George Floyd, a man who was handcuffed after possibly passing a counterfeit $20 bill, lying face down with a cop’s knee pressed to his neck, asking for his dead mother and saying, “I can’t breathe,” as his life drains from his body. Many Americans believed that this was no longer a place where Black people were bought, sold, and hung from trees. They were surprised to learn that Black life matters no more now than it did in 1820. What is fortunate about this moment is that many people have looked and are sickened.”

He also writes about the magnitude of the protests, and why they’re not to be condemned. “I know some people have agonized about these uprisings, but they’re missing the point. These mass protests are among the most beautiful things I’ve experienced in my entire fifty-five years. People across the country—and all over the world—are heroically standing up with tremendous passion and heart to this confusion of police violence, military force, media lies and slander, and threats posed by President Trump. There’s a lot of work to do and a lot of struggle to be had, but we need to celebrate and continue to fight with determination as we figure out how to build a world where all human beings can flourish. Let’s make this count.”

Black, Queer and Holy: The Many Shapes of Black Multiplicity, Frieze (June 9, 2020)

Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung writes on the superpowers of black multiplicity—of expressing all aspects of self beyond the singular.

“Nyong’o got me thinking whether it was Little Richard’s ‘too much’ of anything that really stood in his way. Wasn’t it rather his crossroads, intersections, cuts and overlaps that were the hurdles? What if it wasn’t because he was ‘too black, too queer, too holy’ but because he dared to be queer and holy, while black, or dared to be black and queer, while holy? These are the limits to being multiple in a world that prescribes and imposes singularity.”

The Films That Understand Why People Riot, The Atlantic (June 9, 2020)

Samantha N. Sheppard, an assistant professor of performing and media arts at Cornell University, writes about the acceptance and glorification of white riots in cinema, and the critique of black riots.

“Hegemonic representations of white violence in film spectacularize riots and lionize vigilante justice. D. W. Griffith’s landmark and racist epic, The Birth of a Nation (1915), is a case in point. In its depiction of the Ku Klux Klan as American heroes, the film’s formal devices, narrative strategies, and thematic motifs sensationalize and champion white mob violence in response to enfranchised black masses. Although controversial at the time of its release, The Birth of a Nation was also hugely popular. For white critics and audiences, Griffith did not depict a riot, but a righteous cause, one that helped revive the KKK in American society and birth modern cinema at the same time. The glorification of white rage extends to more contemporary films: David Fincher’s 1999 cult film Fight Club, for example, critiques and valorizes white male violence, vandalism, and domestic terror. And the seemingly innocuous treatment of city destruction in white superhero films such as 2013’s Man of Steel suggests that, in white men’s efforts to “save the world,” cataclysmic mayhem is wholly justified.”

“Literature Can Foster And Express Our Shared Humanity”: Bernardine Evaristo On The Importance Of Inclusive Publishing, British Vogue (June 6, 2020)

Bernadine Evaristo, whose novel Girl, Woman, Other won the 2019 Booker Prize, writes about the consequences of the severe lack of diversity in publishing, and why story-telling is a vital tool for understanding and connection.

“It’s really brought home to me the way in which literature can connect us to each other and foster and express our shared humanity. Our experiences in this country might be specific, but through art we can interrogate universal truths about what it means to be human. This is why it’s so important for our arts, culture and society to be inclusive of everyone.”

Evaristo emphasizes that this movement needs to be more than a PR moment.

“It goes without saying that the industry needs to publish more novels from our communities and at this stage, it really shouldn’t need diversity campaigns to do so… The economic, cultural, creative, and moral argument for diversity was won a long time ago. It’s blindingly obvious that literature’s gatekeepers are the ones to change their culture of exclusion, and many of us are fed up of being asked for solutions to systemic racism when we are not the perpetrators of it…. Any action plan worth its salt needs to offer practical steps to ensure the industry reflects our society, without resorting to tokenism. Putting out a feel-good press release or tweet that promises a change that is never delivered is not good enough. And we’ve had enough of the culture of one-seat-at-the-table, the lone voice struggling to be heard. Top-down inclusion and true integration, from the boardroom to the basement, is the only way to go.”

Enough Already with the Statements of “Solidarity,” Arts World, Medium (June 5, 2020)

Kaisha S. Johnson, founding director of Women of Color in the Arts, writes in a letter to the arts world that the litany of solidarity statements are missing the point.

“As if moving to some syncopated symphony, arts organizations and cultural institutions across the country are parading out statements of “solidarity” in these moments. I’ve stopped counting (and reading) the endless emails I’ve received from arts organizations touting how they stand in solidarity with Black people. Statements which proclaim they’re shutting down their operations and programming—galas and town halls and education programs are “going black.” How cute. Now, all of a sudden, historically and predominantly white arts institutions want to be “in solidarity” with Black folks? I know what solidarity looks like. And it ain’t this.”