Truth to materials. Process. Site specificity.These are terms that critics and art historians have used to describe countless works of art, particularly sculptures, for over half a century. As such, they are catchphrases that might cause readers to glaze over when reading an otherwise insightful review or critique of a contemporary artist’s work. But pause for a moment, and think about what these terms are meant to conjure. Truth to materials: an artist’s obsession with the essential qualities of a specific substance—the delicate porcelain, the luminous graphite, the textured paper—that drives her desire to manipulate it while preserving its integrity. Process: the procedure necessary to wed those substances to an idea that, when conceived, did not exist in the physical world. Site specificity: the resultant object’s relationships to its environment and its immediate surroundings and how honoring those relationships might allow viewers to think about their own surroundings differently, with a more attuned consciousness.

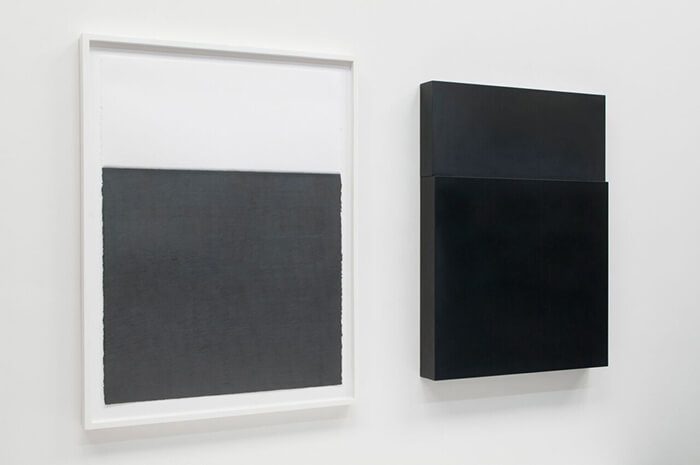

Susan York’s career has evolved over several decades and, in many ways, constitutes an ongoing investigation into materials, process, and site specificity. For the past several years, York has worked with graphite in two and three dimensions. Often, she will translate her drawings into three dimensions, or vice versa, in order to experience how perceptions of size and scale shift depending on their mode of representation. Her own brand of perfectionism has less to do with the final result of her works, which are often deliberately asymmetrical or off-center, and more to do with faithfulness to her own process. She completes a drawing every day, openly acknowledges that sacrifices are part and parcel of living an artist’s life—and yet her work and her approach to it have escaped a severity that often befalls such regimentation or austerity. We spoke to York about her practice, her plans for the future, and her forebears at her studio as she prepared for an upcoming solo exhibition.

Chelsea Weathers: You have a show opening in October at the Drawing Center in New York. Can you explain what you are planning for that show?

Susan York: It’s in the basement of the Drawing Center, and it’ll be up for at least a year. In that space, I measured the exit sign, the fire alarm pull, pipes in the ceiling, and the rocks from the foundation that come out from the wall. I actually got my daughter who lives in New York to do some of the measurements of the space for me, too. I’m really interested in the granite foundation, which holds up massive brick columns. I love the stones, and a lot of people don’t notice them, so I really want to magnify their presence. The stones are being replicated in graphite. As you go down the hallway, mine will gradually become more geometric. I’m making 1:1 scale drawings of the stones sited at the bottom of the paper, the same way the foundational stones rest on the floor. For the drawings, I’m making two versions of the stone foundation. They won’t all be shown, but one will be a replica and one will be geometric, where I’ll basically straighten it and flatten it out. I’m also working on two beams that relate to the ceiling measurements, a fire alarm pull made of graphite, and an exit sign, which I might or might not show. There’s a square plane on the floor that’s going to be replicated, along with some joists. I want the whole to be a Gesamtkunstwerk [total work of art].

For a long time I didn’t know what I was going to do. You know that period before you don’t know what you’re going to do, and it’s like being in a dark room and you’re trying to just figure out what the shape is? That lasted a really long time with this project. Not because I didn’t know what I wanted to do so much as I didn’t know how to make it, how it would happen. Everyone I spoke with told me it wasn’t possible to make the stones in graphite. But I eventually put together an amazing team. 3-D scans were made of the stones, and then they were CNC [Computer Numerical Control] milled. I worked with a 3-D modeler to draw the planes so that the graphite stones subtly transition to planar forms.

CW: I had a teacher who told me once that even when I wasn’t working, even if I didn’t know I was thinking, I was thinking. It was such a relief to hear that.

SY: Isn’t it? I think procrastination is sometimes, not always, but sometimes a misnomer. I think it should be called rumination. Because some of us need a lot of time to just absorb it and then translate it out of ourselves.

CW: I think it takes a long time to realize how you work and then to create the circumstances so that you can work.

SY: And maybe just to accept the way you work… These are my daily drawings. That’s 2015, and around the corner is in 2017. I do one every day.

Clayton Porter: Why do you do them?

SY: I was thinking that doing something every day would be a good thing. What it does for me now is, if I did it yesterday and I do it today and tomorrow, the level of risk is almost nothing. So I enter new territory in a way that I don’t with other work. My work is really prescribed, and I often know exactly what it’s going to be before a pencil touches the paper. But if you look at the daily drawings, you can see variations that you don’t usually see in my work. Like last night, I just did this table with stuff on it. And from memory. I never do stuff like that.

CP: What’s the average time that you dedicate to a daily drawing?

SY: It really varies. It’s not usually more than three hours. Sometimes it is quick. My only rule is I have to be done by midnight. I can do anything I want. I even think about that: you can do anything you want! How often in the day do you get to do that?

I think procrastination is sometimes, not always, but sometimes a misnomer. I think it should be called rumination. Because some of us need a lot of time to just absorb it and then translate it out of ourselves.

CP: When did you start the daily drawings?

SY: 2015. But then I didn’t do 2016, because I didn’t want it to be prescribed. I want it to always be me being pushed off a cliff, instead of…

CW: Getting into a routine?

SY: Yeah, kind of. A lot of times it’s like brushing my teeth, which I think is a good thing; it’s just part of a day. But I don’t want it to be too known. I may do it next year. I don’t know. I’m going to follow my instincts.

CP: Do you think you could have done the daily drawings throughout your life, including the time when you were raising a child?

SY: That’s a really good question, and I don’t know. I think I probably could have, because I’m so driven. I always tell students that if you want to be an artist you have to be willing to hang by your fingertips off a five-thousand-foot cliff a lot, because it’s not the easiest thing. So I think I probably could have. In fact, the week I gave birth I had a show open. So probably?

CW: I know that Agnes Martin was one of your mentors. Who else would you count among your mentors?

SY: I went to grad school late. I was in my forties, and I had a really dedicated studio practice during the twenty years in between undergrad and grad school. But I couldn’t quite get to what I wanted. You know when you fall asleep and you wake up, and you can’t quite remember the dream? It was like that: there was something I needed to get at, and I couldn’t quite get at it. So I really looked assiduously for the right school and the right teacher. I ended up taking a workshop with Tony Hepburn, a British sculptor/ceramicist. At that time, he was teaching at Cranbrook, so that’s why I went there. He really helped me find my own vision. I wanted to do ceramics, but he wouldn’t let me work in clay, I hardly worked in clay the whole time; I just worked in sculpture and drawing.

CW: And were you doing sculpture before?

SY: I was doing ceramic sculpture. And he said, “You know it too well.” So maybe it gets us back to the daily drawing.

CW: Not wanting to feel too comfortable.

SY: This last year has been an excellent example of that.

CW: So you went to UNM for undergrad, and then you took a break for decades?

SY: Yeah, I went to UNM in three years.

CW: Was your training there really traditional? At what point did you land on abstraction? Was that slow?

SY: That was a little bit slow. Somebody brought me something I made in undergrad that’s a flag puzzle. It’s a protest—it’s a flag that’s in pieces—and the lid says, “Do not bend, fold, spill, or mutilate. Do not hang upside down.” Something like that.

CW: The rules of the flag?

SY: The rules of the flag.

CW: When was this?

SY: The early ’70s. It was during the Vietnam War. I also did—I wish I still had this one—an army boot with blood on it, glazed ceramic.

CW: So you were doing kind of political activist representational…

SY: Apparently! I remember pushback in undergrad. They were like, “This is not what you’re supposed to be making with clay. You can’t hang it in a tree!” I went more into abstraction maybe ten years later, when I got a slab roller. I did these ceramic pieces that were pretty literal, so eventually I just rolled the pieces out flat and did color studies. And it sort of evolved.

CW: You often get associated with minimalism. Lucy Lippard, for example, has written about your associations with and departures from minimalism and post-minimalism. How much do you feel aligned with that history?

SY: I think it’s a longer legacy because—in the big Janson art history textbook there’s this [Gerrit] Rietveld chair, and that’s the only picture I remember from that entire book. And it took me more than twenty years to get to Rietveld’s home to see the chair in person. I also saw this Malevich show in the early ’80s, and I couldn’t talk for two days. I just felt like I’d met my ancestors. I mean, really, I could still cry thinking about that show. I think they’re the minimalists’ ancestors.

CW: Malevich was much more interested in spirituality than a lot of the minimalists, at least outwardly. And that’s something that’s present in your work too.

SY: There’s this amazing Malevich quote that’s something like, “My work is like a house being eaten up by termites.”

CW: What does that mean?

SY: That it’s present, and it’s appearing and disappearing at the same time. I don’t know if he would have said that, but that’s how I see it. It’s a rising and falling, constructing and deconstructing. Like this piece here, these four cubes, they kind of merge into the environment and fall away at the same time, because they take up the reflection of what’s around them. This one was actually one of the first ones I made.

CW: Is your process with graphite experimental, or do you have a clear idea of what you want before you go into it?

SY: I have a clear idea of what I want before I go into it, and then basically we cut and shape it. But some of the blocks I cast myself. It’s almost like a ceramic process, and I started in Holland, actually, because they make master molds using graphite and sulfur. It’s almost this medieval process; it smells horrible.

CW: The large column you showed at the Lannan Foundation was about a thousand pounds. And I didn’t realize graphite was that heavy—I always think of graphite as this airy, light substance, like pencils and charcoal.

SY: It weighs one hundred pounds a cubic foot. Another person I worked with in sculpture when I was casting solid aluminum at Cranbook said, “Susan, why not just make a hollow center? It’ll make everything easier.” And I couldn’t bear to. Because I just wanted them to be truthful.

CW: What do you use to fabricate the graphite works?

SY: We have two CNC machines that we got at auctions when Los Alamos and Sandia got rid of them. They’re from the ’70s. Basically it moves in four directions, and you can see the tracks as the tool moves. So that’s how the stone piece was made, and that’s how the sphere was made, too. It’s like a 3-D printer, only the opposite, because it’s subtractive.

CP: Is this intimidating, in terms of your practice?

SY: Well, [my husband] Chris Worth was a software engineer, so he was really excited about it, and until I understood it, I couldn’t have cared less. But then when I drew the circles and started modeling them in three dimensions, I realized what it could do.

CP: So it’s good having a partner who can give you help?

SY: Totally. I think also nowadays, luckily, we can have teams, if we can manage that, and that really opens things up. For instance, the pieces for the Drawing Center are being made by a robot.

CW: And you have a kid in New York who can go do measurements for you!

SY: I know, and she’s so nice about it!

CP: Will graphite remain your primary medium?

SY: I think so. I have some experiments in glass, so I’m starting to look at other materials. I think graphite’s pretty good, but I’d like it not to be the only thing I do. There are a few other things I want to try to experiment with and see if I can get them to work. The problem is that everything I do requires a lot of process.

CP: Is there any type of consideration when you movethrough mediums in terms of collectors, recognition, institutions, support? Is there a consideration of whether you should rock the boat by bringing in new mediums?

SY: I feel like I can keep doing all of them. But what I do think about is being true to what I think the materials should be, so the glass has to be solid. It has to be what it is and not anything else. When I was making porcelain pieces, I would pour these thin porcelain shards. And there’s a kind of elemental quality to that. I would say the graphite is more elemental, but bone china is pretty elemental. So that’s what I think about. I have amazing collectors, and I think they’ll come with me. It’s sort of like artists––I’m sure you have a core group of colleagues. The collectors are like that too. They get what I’m doing, and they support me, and they also speak the language.

CW: Have you done anything lately where you had high expectations and it didn’t turn out the way you wanted?

SY: I did these pieces in grad school that I formed with gravity, so they were spheres. But I did them on a latex diaphragm so they would get kind of pulled by the gravity. I wanted to do some more of those, so I did some experiments, and I couldn’t get it to work the way I wanted it to. And then I’ve been playing around with plaster a little bit. I haven’t gotten that to go where I want it to go.

CW: It’s interesting to hear about experiments.

SY: I feel like that’s what the daily drawings are, too. Every day’s an experiment.