The tone of my studio visit with Santa Fe artist Ted Larsen was set early when he declared that he would likely be both circumspect and like a blowtorch when talking about his thoughts on his studio practice, life, and work. Now fifty-five, the trained painter has been showing his art since before he graduated college. By the time he was twenty-two, he had already exhibited at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, making big strides early on in a career that has now spanned decades.

This wasn’t my first time visiting Larsen’s studio; we’ve known each other for several years. In that time, we’ve rendezvoused infrequently to discuss the commonalities we face on the sometimes-challenging journey of being an artist.

My first introduction to Larsen’s work was during my time as a freelance art installer. Over the years, I put up a few of his sculptures in group shows, but when it came time for a solo exhibition, he requested to install his art and light the gallery space himself. As odd as I thought it was, I came to realize while watching him work that he was in constant dialogue with his sculptures, intuitively hanging the show without the conventional geometry.

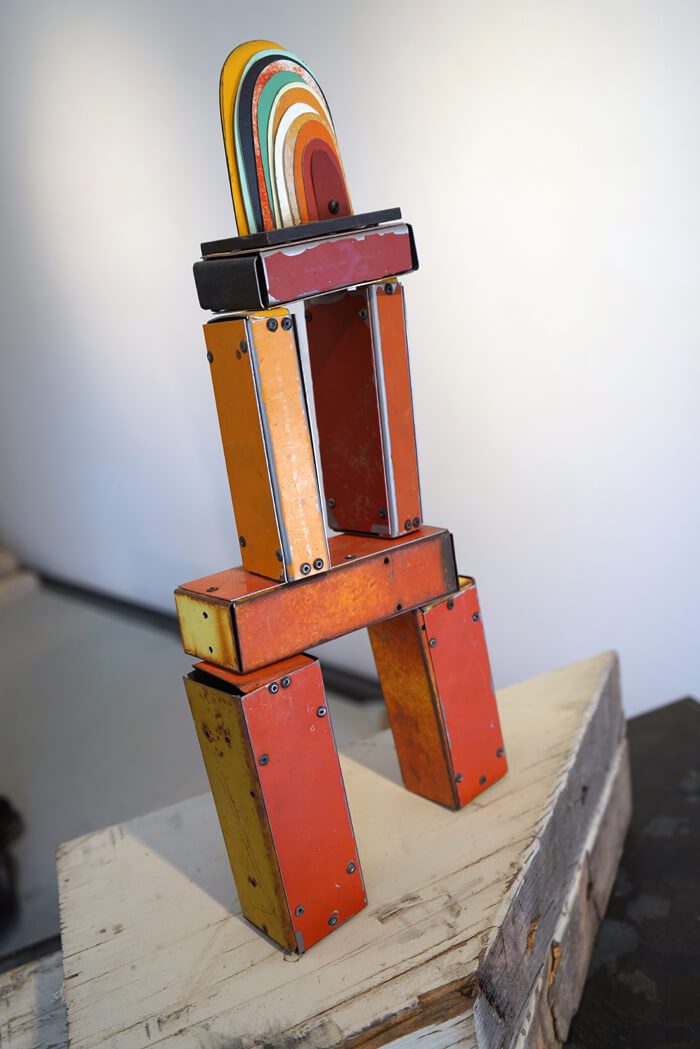

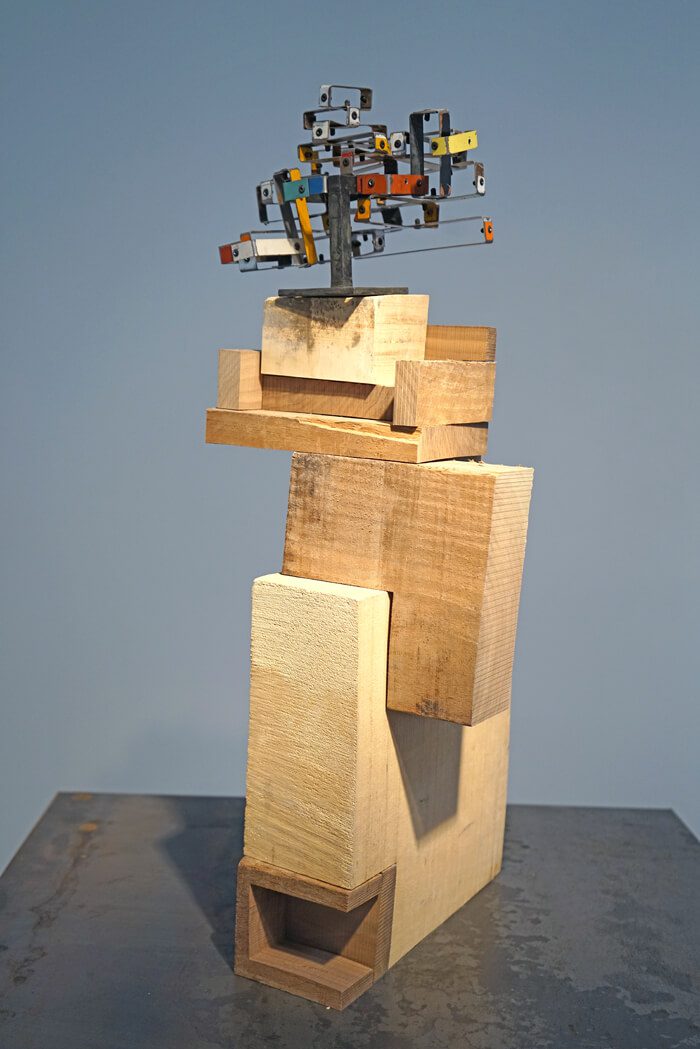

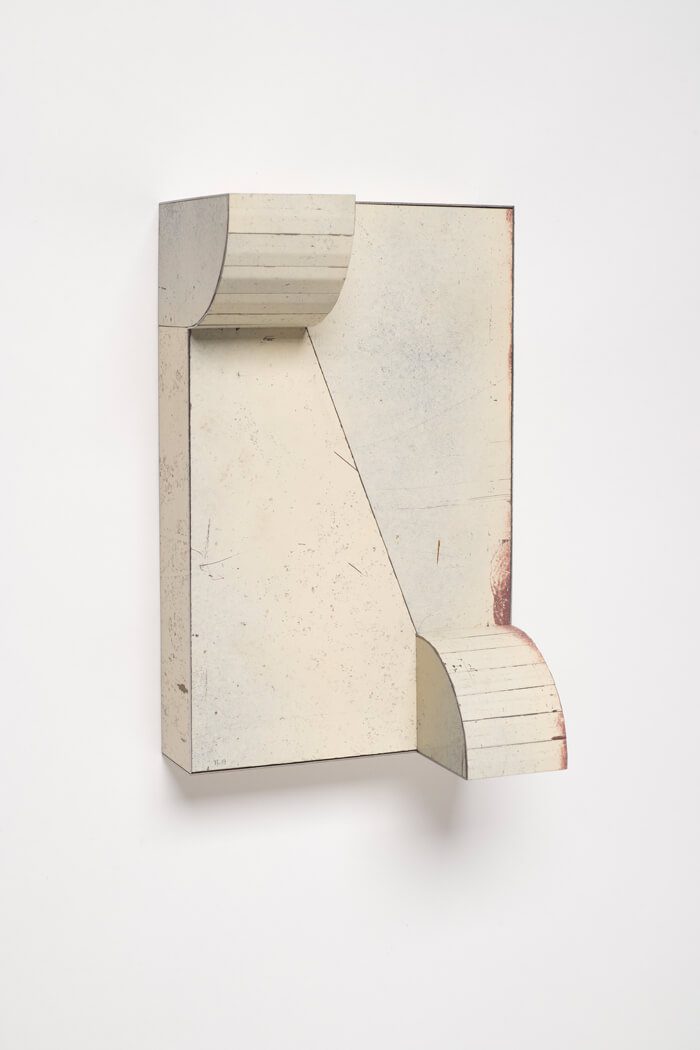

Larsen’s sculptures are generally constructed out of reclaimed metal that the artist cuts from the body panels of old cars. The paint tends to be faded and matte, the colors familiar and weathered. Many of the sculptures have a laminated wood core that is then skinned over with the metal Larsen exhumes from the scrap yard. They’re heavy in a way that makes them feel substantial when held. Though typically hung on a wall, it’s a mistake to ever assume Larsen’s work stays within the confines of what’s expected.

As often as I’ve seen the sculptures mid-process, if asked how they are put together I’d be hard-pressed to give a good explanation. I believe this is a part of Larsen’s intent. The precise and intricate ways the sculptures are assembled don’t overshadow the visual experience of the whole. When admiring the sparkles of a diamond, who stops to think about the refined labor it takes to cut each facet? Like a diamond, Larsen’s sculptures captivate and provoke contemplation from the viewer without the artist interjecting himself.

Clayton Porter: In previous conversations, you’ve said the art you made earlier in your career was different from the work you make now. However, I’ve never asked you how it was different and how that process of change came to pass.

Larsen: I was trained as a painter. I still think of my work as painting, even though it’s not. I still think of it as painting, because I approach it in the same way.

I graduated from college when I was twenty-two. I was really pretty lucky right from the very beginning. My history of making has been uninterrupted since that period of time. Between the years 1999 and 2000, I was wrestling with some things in my painting that I didn’t really understand. I was unsatisfied with something that was going on in the work. I didn’t actually know what that was, as funny as that is to say, and it took until 2001 for me to piece it together.

What was the painting like?

The kind of painting that I was involved in had a certain [quality of] simulacra to it. It was a proximal relationship to something of the real world, but it wasn’t real. There was a “faux” involved, and I didn’t want people to see certain things in the work—but if I didn’t want them to see it, maybe I shouldn’t show it. It was actually very simple, but I believe that sometimes artists are the last people to know their own work.

What was the transition from that work to this work like?

Well, when I was twenty-two, I’d already had a lot of really substantial things happen in my career, some of them happening before I graduated. So there was a certain kind of inertia and trajectory that I was on that at first was fine, but then, over time, the challenge became growth. How do you move freely, when there’s an expectation for something to be a certain way? That expectation was both internal and external. I had an expectation, and people that knew my work had an expectation, and it took me a really long time to move past that perceived duty to both myself and others and allow myself the freedom to fail. Failure is really hard. It’s hard to risk doing something poorly when you’ve come from doing something well. When I was young, as an athlete, failure is not something that you’re encouraged to have. What I learned by being willing to walk away from something that was successful and had meaning to me was an ability to be more successful, an ability to have more meaning in my work.

I don’t want my work to be prescriptive. I don’t want there to be a specific takeaway. It’s not about salvage or recycling or re-purposing or consumption, or any of those things, and yet all of those things are part of what my practice is.

What did that willingness to walk away and fail do for you and the work?

It unburdened me as a maker from having to create meaning. The work that I make now is formal, and it addresses formal issues. I don’t want my work to be prescriptive. I don’t want there to be a specific takeaway. It’s not about salvage or recycling or re-purposing or consumption, or any of those things, and yet all of those things are part of what my practice is.

Were you apprehensive about turning away from success when there was a real possibility it might not come back?

At first, it was really hard for me to walk away from something that I was known for and successful at. But walking away from it gave me a freedom that I would have never had, had I not been willing to walk away from it. I was only willing to walk away from it because of a core dissatisfaction… and a willingness to do anything to not experience that [anymore].

At what point into your career or at what age did you realize that dissatisfaction?

I was about thirty-five when I started exploring that sense of dissatisfaction. Unbeknownst to me, that dissatisfaction was not just within my studio practice; it was something that was at the core of me as a person. At age fifty-five, I feel like I’m closer now to my authenticity than I’ve ever been, but I’m still getting there, and I feel the same way about the work.

Easy answers and pristine things don’t interest me. Things that are kind of funky and rickety and cobbled together and provisional, that are provocative, are more interesting. I’m much more interested in interesting questions than good answers.

In what way do you get there?

I have an active investigation happening in the studio, [but] I don’t really know what I’m investigating. I don’t know how to describe it, probably because I want it to be mysterious to me. That keeps me engaged. Easy answers and pristine things don’t interest me. Things that are kind of funky and rickety and cobbled together and provisional, that are provocative, are more interesting. I’m much more interested in interesting questions than good answers.

How do you feel about your older paintings, during those transitional years, existing in the world now that you and your work have evolved?

It’s fine. They exist. It’s different than what this is. One of the things I try not to do in life is to be a critical hardass, because if I turn that switch on, good things don’t normally come from it. It’s important for me to be critical of my work but not critical [in life]. Knowing where one ends and the other one begins is important.

Let’s switch gears and talk about the commercial aspects of your work. You show with galleries nationally and internationally. Does that have an effect on your practice?

On one level, the people that I work with, the galleries that I work with, they have their job, and I have my job. Their job is different than my job. I try not to get involved in their job, and I don’t let them get involved in my job. I have a one-on-one relationship with them, but they don’t have a one-on-one relationship with me. I work with seven galleries, but each one of those galleries might work with ten to fifteen different artists. We share a commonality, and that’s where I have to leave it. On the other level, they have to be on board with what I do one hundred percent. There’s an existential risk to making work. A risk of great peril. If it’s done poorly or wrong, the artist suffers for that, so the gallery has to be willing to sponsor that level of risk. If they’re not willing to take on that mandate, then they have no business working with me or anybody else.

I’ve learned way more, on every level, in every possible way, when I’ve made mistakes in my life than I’ve ever learned from my successes.

Do you let anyone offer you feedback on the work inside or outside of the studio?

I have a very small group of people who I trust as second eyes, as people who can speak truth to me, who can come into my studio without bringing their own agendas. It’s hard to find true dialogue. It’s always appreciated to have an “attaboy,” but it’s not very meaningful to have somebody come in and pat me on the back and go, “I like what you’re doing.” What is meaningful is true dialogue and it can be hard to find. Funny enough, I generally don’t ever ask the galleries. They’re all friends: I mean, all the people that I work with I would love to travel with and, you know, share a meal with and talk about life and things, but what they see in something I make is generally not something I ask them.

Why not?

I think it’s a little bit of a conflict of interest. It would be getting into the more commercial aspect of things. It’s about commerce for galleries. That’s what they do: they sell things. And I do sell my work, but that’s not why I make it. I make it for myself. It’s a bit of a tightrope walk, a balancing act, and it’s not always easy. You can misstep, and I have misstepped. I’m not always perfect. I don’t want to be perfect. Actually, I’ve learned way more, on every level, in every possible way, when I’ve made mistakes in my life than I’ve ever learned from my successes. I don’t relish making mistakes. I’m never happy that I’ve made one, but I always look for ways to understand myself more fully having made them.