Visiting Stuart Arends’s studio was no quick jaunt. We drove one and a half hours from Santa Fe to Willard, New Mexico, past the town, further down the highway, and just before a specified mile marker where we were to rendez-vous with the artist at an unmarked wire gate.

Arends met us in his Jeep, and we followed him down a long stretch of white dirt road, finally arriving at his live/work studio, a small slant-roof metal building, with cleverly elevated sliding patio doors repurposed as oversized windows.

The artist has been living on the ranch for the past thirteen years. I asked how he felt being in such a remote location. “I feel safer out here than in the city,” he said. “When a friend of mine learned I was coming out to New Mexico, he told me that there is a saying—when you take someone, put them in the desert, and make them live there for a year, they’ll never live anywhere else.”

Arends is no stranger to living in isolated communities. He grew up in Iowa farm country, lived in several sparsely populated towns in Canada, and—after a year at the Roswell Artist-in-Residence Program—built a house in the Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge. He describes isolation as feeding his work.

Walking into his studio outside of Willard, I thought I’d entered a minimalist décor catalogue, or as Lauren put it, “very Instagram-able.” As unexpected as it was, being in ranch country, it seemed all too familiar. At the end of so many art pilgrimages—Willard, Marfa, Naoshima, Beacon—there tend to be unexpected art spaces and artworks, but in these unique locations they end up completing one another, like setting a diamond in a ring. Artists have long sought out the American Southwest for its isolation and the solace of the hinterlands, and Arends is cut from the same cloth.

Stuart Arends: Generally, I work really small. I went through a period after graduate school where I did really, really large things, but at one point, working that large stopped making sense. I started making small things during graduate school, but thought a person couldn’t have a career making little things, so I did really big things. One day I was looking at them, and I said to myself, “They have a lot of wow factor—really big, really bright—but it didn’t go much beyond that.” So I found out that things don’t necessarily have to be big to draw people in and have them focus on the same things that they should be focusing on in the big works, but can’t because they never get close enough. So I destroyed all that work.

Lauren Tresp: You destroyed them?!

Yeah, I destroyed five years of work. They were sitting in storage in LA, and I thought one day when I’m famous, that work is going to be worth a lot of money, but after a few years of paying for the work to sit and collect dust, I decided instead to hire a guy with a big truck and load it all into a dumpster.

Clayton Porter: Was that regrettable?

Oh no, it’s like a weight comes off. I used to have a lot of stuff, and I got tired of moving it, especially when I was moving a lot, and so the same goes for my studio. I’m a real severe editor: I throw away a lot more than I keep. I don’t have kids; I live alone. So when I go, do I want to curse somebody with all this stuff? No. I just keep it pared down to the best, just the best stuff.

Clayton: Did that sensibility take time to develop?

Living in Canada, I set up a studio and painted two watercolors every day for a couple of years. When it was time to leave, I had an old van, and whatever didn’t fit in the van had to go. I went through my studio and went through all the works on paper. I built a fire in the backyard, I tore the artworks into pieces, and fed them into the fire. I saved twenty pieces out of more than three hundred works. Destroying the first one was painful, but as you go through them, the load starts getting lighter, and it’s like taking back every bad thing that you’d ever said about anybody; keeping the work becomes like a ball and chain. I knew I could make more and that they’d be better. It was a liberating experience to get rid of all that stuff.

Clayton: When do you know when to get rid of a piece?

When I finish something and I don’t like it, I hesitate before throwing it away. If, after a while, I come around to it, it’s usually one of the better things that I’ve done. If it takes me a while to like it, that usually means that I have to stretch my boundaries, and the definition of what my work can be. I never pitch something too quickly, but when I decide the piece is no good, it’s gone. I always need firewood.

I knew I could make more and that they’d be better. It was a liberating experience to get rid of all that stuff.

Clayton: Do you do anything else for income besides art?

After coming back to New Mexico, from LA, I was asked to run the residency program in Roswell, which I did for a few years. That was twenty years ago, and it was the last job I had. One of the reasons I like living out here is because it’s off the grid and I don’t have any bills. There are years when you do really well, and there are years when you don’t. Making the work is important to me: it’s one of those things that I need to do, not something that I want to do. Why would anybody want to do this? So I understood, many years ago, that there would be good years and there would be bad years, and I’d have to be able to survive those bad years.

Clayton: You said, “Why would anybody want to do this?” What do you mean?

It’s not just the business end of it that’s challenging, but it’s a difficult thing, to go into that empty space and be confronted by these materials. Every time I put a new support on the wall, I don’t know if I can do it again. It’s like I’m confined to all the knowledge I have to give to that piece in order to make it meaningful for somebody to be able to respond to it. That’s tough. It’s very intimidating to face it.

The money thing doesn’t mean that much to me, otherwise I would’ve done something else. Being out here is like heaven. It’s all I need.

I always say you make the work because it needs to be made. I made a body of work called Celadon because they were painted celadon green. They were really difficult for me because they were outside of anything I knew how to do. It took me a couple of years, and I knew there was something there, but they were the most pared-down things I had done up to that point. I had a show of the Celadon works with my gallery in LA at the time [1990], and after installing the work, they told me that a lady came into the gallery the day of the opening. Looking around, expecting to see the show, she asked when they were going to hang it. The show was hung. She had missed the work.

So that show went up, and I didn’t know what to make of it. It was even too weird for me. I got a curious review in the LA Times, and my gallery didn’t sell a thing. I came back to New Mexico and I got a call from my gallerist and she said not to worry. She said, “We’re a gallery and we have to make money, but sometimes we have to do what we think is important and what we believe in.” A week later, she called back and she asks if I’m sitting down. “Should I be?” I said. The Panza Collection had come in and bought the whole exhibition.

So you’ve got to follow those drives; when you’ve got to make something, you gotta make it.

Lauren: How did you get from working in two-dimensional to three-dimensional work?

I went to Western Colorado University, and the art department was really all about the basic fundamentals; it wasn’t about creative thinking. So I came out of there as a fairly facile, fairly proficient, traditional watercolorist. After that, I started a gallery and business with a friend and kept painting, but I started to get frustrated with things. I started thinking, there’s got to be something more than just doing landscapes. So I started doing some more abstract things, looking at artists like [J. M. W.] Turner.

When I was living in Canada, making two paintings a day, I painted a piece called Sienna Splash, put it in a frame, and was looking at it in the studio, when—I kid you not—the painting disappeared. It just disappeared. It became a window and I was looking into an alternate reality. The illusion of picture space totally took over; it lost any sense of surface and any sense of marks on it. It weirded me out, and I thought, “That’s not right: the artist’s hand, the artist’s touch has to be there.”

I went back into the studio and started over. I tried to make a mark on a surface that would stand as the mark and not be open to interpretation. I worked on that for a long time. I didn’t know where I was trying to get to, but I knew that wherever it was—that I was—it wasn’t it.

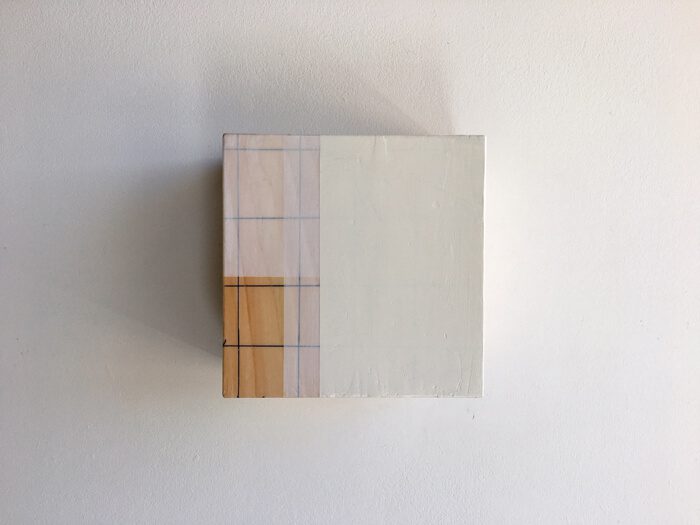

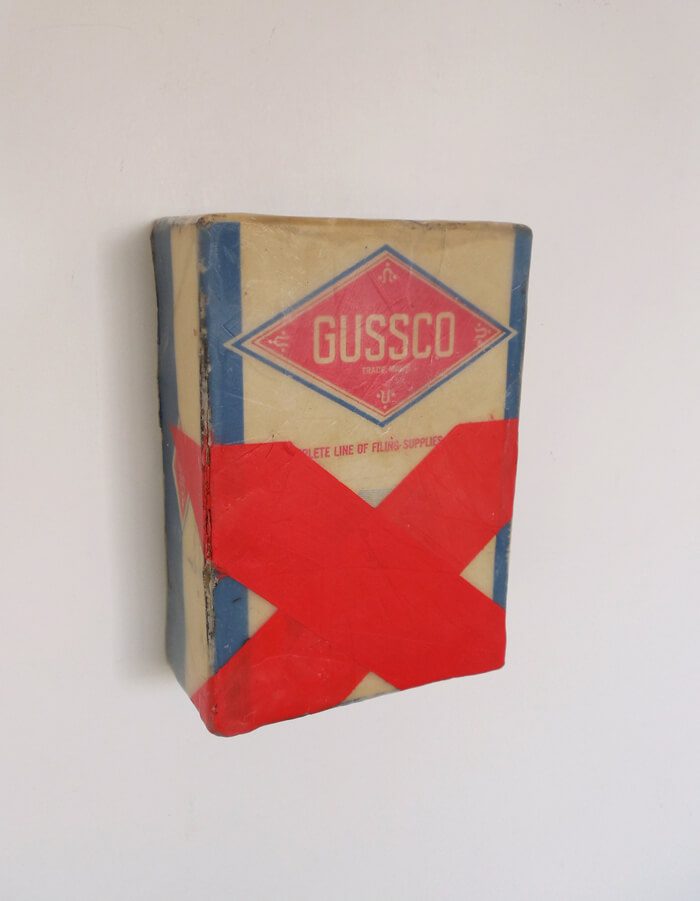

After moving to LA, my canvases started getting smaller, and I started working monochromatically, but the paintings could still look like something else: you could still look at it and interpret it as something other than paint on a surface. I was getting really frustrated. So there was this cardboard box on the floor of the studio. I picked it up. I had red paint on my palette; I painted it red and put it on the wall, and that was it! There was no way that you could look at that box with paint on it and think of it any other way than a box that has been painted red.

That was the start. That was when I started dealing with paintings as objects.