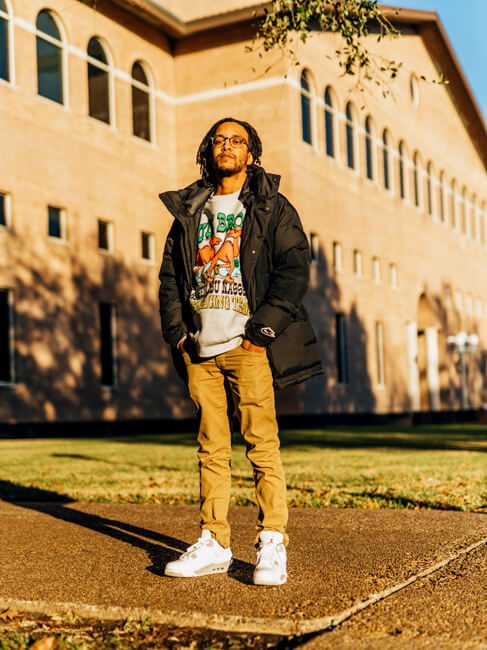

Houston-based artist and graphic designer Phillip Pyle, II upholds a tradition of collaboration in the historic Third Ward neighborhood.

Houston’s historically Black Third Ward neighborhood is known for its inclination for collaboration in the visual arts. From the midcentury founding of the art department at Texas Southern University by painter and muralist John Biggers to the establishment of Project Row Houses in 1993, socially engaging artwork from decades of talent has provided cultural enrichment to the local community. Artist and graphic designer Phillip Pyle, II, resident of Third Ward, carries on this legacy of collaboration in his current practice. Using the language of graphic design, Pyle questions the changing landscape of a neighborhood increasingly losing its historical landmarks and character due to gentrification.

Most recently exhibited in the 2021 Texas Biennial, Pyle has been showing his work for nearly a decade at Houston art institutions such as Project Row Houses, Art League of Houston, Houston Museum of African American Culture, Lawndale Art Center, and DiverseWorks, as well as contributing to public works throughout his Third Ward neighborhood.

Currently completing his master of fine art in photography and digital media at the University of Houston, Pyle credits early formative experiences available to him through his community. “A lot of my early art education was done right at Project Row Houses, so social practice and community-engaged art falls into the foundation of everything I do,” Pyle says.

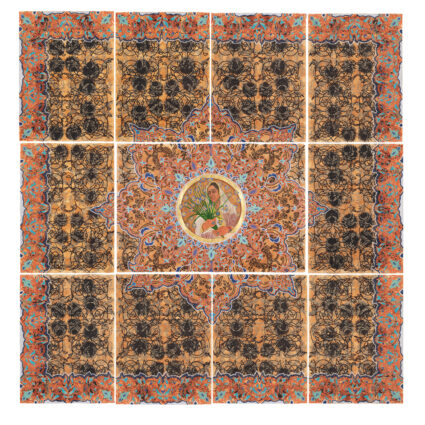

Two of his earliest projects that bring attention to Third Ward’s changing landscape include Third Ward Monopoly Club from 2012—a group of artists and community members gathering to share ideas and play the board game—and an installation in a Third Ward vacant lot called Beauty Box (2013) created in partnership with fellow Houston artist Robert Hodge. With his strengths in graphic design, Photoshop, and quick wit akin to freestyle rap, Pyle is confident in the abilities he brings to his artistic alliances.

“I was twelve years old when I heard Wu-Tang for the first time—so I would say that they have a great influence on my drive to collaborate and bring people together to build on things,” he says. “I know what I’m good at artistically, and then I’m friends with somebody that’s good at something else artistically. So, I just never overlook the notion that this can be even better if we work together on this project.”

Drawing from artist Fred Wilson’s brand of conceptual art, Pyle often mines archives for imagery and libraries for history books that overlook or do not elaborate enough on the voices and histories of Black people and people of color. For example, Beauty Box (2013) brings attention to a specific moment in Third Ward’s history of a thriving and proud neighborhood with green lawns and maintained homes, reflected in found photographs from the 1960s.

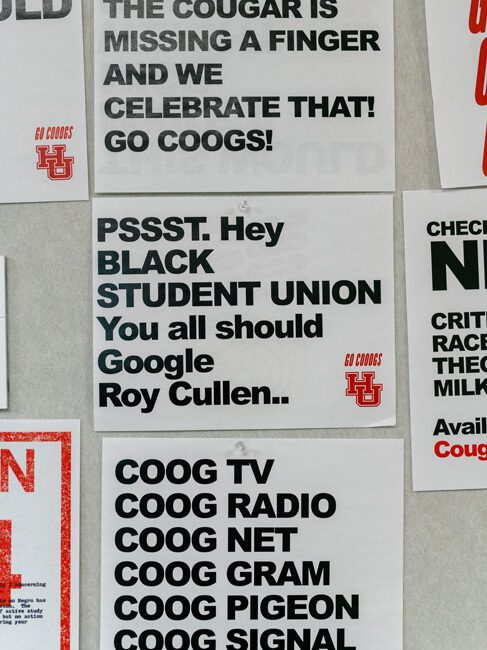

Historical documentation continues to influence Pyle’s oeuvre. During the pandemic, Pyle teamed up with fellow Houstonian and archive enthusiast Jamal Cyrus for an Instagram takeover of the Blaffer Art Museum’s profile. Pulling images of leaders in local civil rights demonstrations on the University of Houston’s campus and throughout the city such as Gene Locke, who advocated for the desegregation of the campus, and Lynn Eusan, the first African American homecoming queen and Black liberation leader, Pyle and Cyrus shed light on significant historical figures in local Black histories and exposed the contentious nature of hegemonic historiographies.

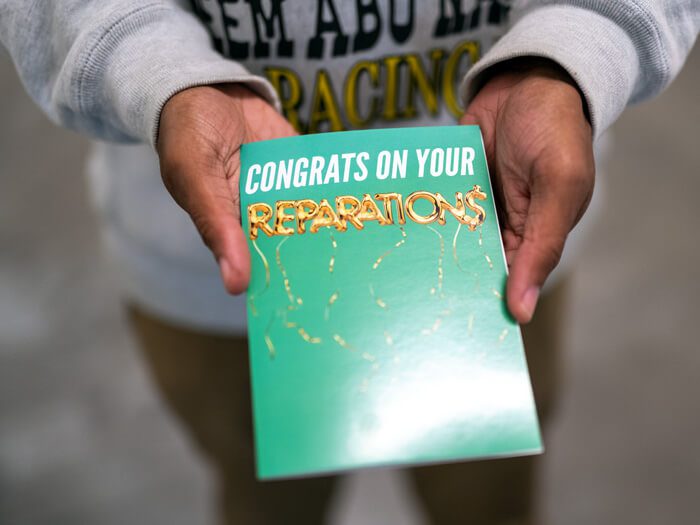

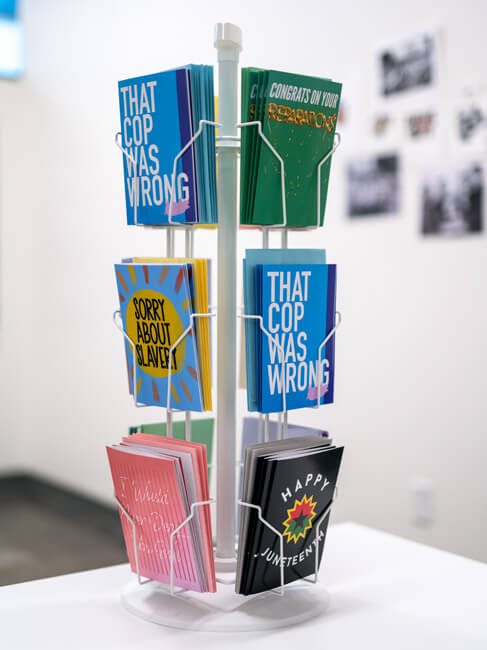

As a full-time graphic designer working at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Pyle is proficient in the language of design and its need to make an immediate impact. Through his position at the museum, he has spearheaded collaborative projects that pull in other Houston artists. Most recently, this includes merchandise for The Dirty South exhibition and a partnership with the Houston Rockets on limited-edition posters that paired local artists with legendary athletes.

His space at the newly constructed Elgin Street Studios on the University of Houston campus provides him a quiet space to brainstorm and bring concepts to life. “I use my studio space primarily to hang in-progress work, sort of like a huge vision board,” Pyle says. “Since most of my work is on the computer, I have the flexibility of creating anywhere, but the studio is where things move from the computer to tangible works.”

Whether in his artistic or professional practice, Pyle’s approach to collaboration is a means of communicating and cataloguing the multifaceted experiences of his family and friends. “When community-engaged art is your bedrock, you aren’t just making art but trying to make different sorts of things that will appeal not only to the community but African Americans and people of color at large,” he says. “I try to make art that the community may not necessarily like, but that will address their concerns and things that they see.”