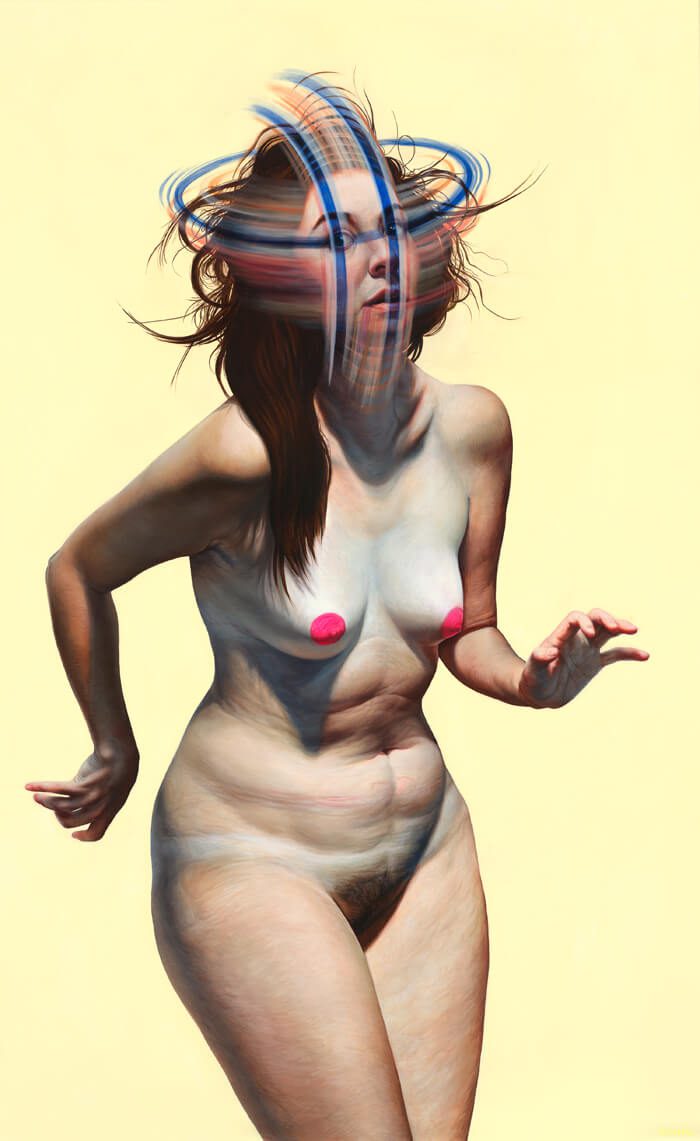

Dorielle Caimi’s paintings have been described as absurd, humorous, truthful, and empowered. Those adjectives adequately describe Dorielle the painter, too, though I would add that she is extremely funny, smart as a whip, and masterful in her execution and rendering of the female figure. Both articulate and open in speaking about her work, Dorielle effectively integrates her emotional and physical experiences into her studio practice. Balancing expressive and brutally honest portrayals of the female form with jarring pop-surrealist color, animal characters, and cartoonish elements, she offers viewers something vibrant and complex. At the heart of her work is an effort to elucidate a specific feeling or experience. Though each painting is deeply autobiographical, Dorielle is able to directly transmit the emotional content of her subject matter, making each painting surprisingly—even arrestingly—relatable. With a well-earned national and international show record, Dorielle lives and works in Santa Fe and is currently represented by Gallery Fritz.

Kate Wood: You paint the nude female form in a non-sexualized way.

Dorielle Caimi: Correct.

What experiences, emotions, or expressions are you trying to access within and beyond the female form?

The work is challenging because most of my figures are naked, but they’re not sexualized. The way I like to describe it to people is, it’s like they’re standing in the bathroom, having a dialogue with themselves in the mirror about something completely not related to their bodies, to their image, or to gender roles or stereotypes. It’s completely childlike in a way, and I like to play with that idea, because we all went through puberty and then you start to notice, like, “Jesus, everyone is sexualizing me and my friends, and they’re hardly taking into account my sense of humor and the fact that I love anchovies, and I’m being seen so one-dimensionally.” So I like to paint women that way, and I also like to paint them as children in their skin, just sort of standing around being in their skin, comfortable in their skin. Or not comfortable.

What relationship do you have to have with your own body in order to make this work? How has your relationship with your body changed since making this work?

That is such a great question! And it is something I think about. I have to have a very positive relationship with my body. I used to have a very negative relationship with my body, and everything was gross. I don’t know; maybe it’s that I’m getting older, but I think it’s because I paint myself that I’m so appreciative of the way my body is built and is formed and the way it moves. And, you know, I love to paint it, so it has taught me to love my body. That’s something I get a lot, especially from female viewers—that they have felt that they’ve seen their body in a new way. Before they thought it was ugly, and now they see it as beautiful.

You mentioned skin and there’s a tremendous departure from your earlier paintings to how you’re able to render skin now. What potential did you realize you were missing in skin? Or what potential did you recognize in giving more to skin as subject matter?

I think the realization that I needed to learn how to do skin better came from seeing, particularly, women’s bodies rendered in a very simplified and conventionally smooth way. And that’s fine. I just think we have a lot of it; we have enough of it. So I wanted to paint more realistic skin—and curves and pockmarks and holes and things that made skin real, like seeing veins underneath the skin. So for me that became an important tool in my language, because I needed to talk about women. I’ve been doing work surrounding women, women’s issues, and my personal issues for fifteen years. I wanted to really represent realistic bodies, so I decided it was worth it to paint skin more realistically. It was hard, but it was fruitful. I had to really focus, because I only had a little bit of formal training when it came to figurative painting. I didn’t want to go get formal training from an atelier or a program where there are a lot of artists going and learning one method of painting the figure, because I didn’t want it to look that way; I wanted it to be my own. There are a lot of people who go to these classical ateliers, and they come out and they know how to paint the figure really well because they were given a specific way of building up the figure. My way is chaos.

The authenticity and honesty with which you depict the female form pushes the figure to a point of genderlessness, where the bodies exceed their anatomical classification in a moment that is relatable beyond anatomy.

Exactly. My work has a lot to do with life experiences and emotions and trauma and grief and things that transcend gender completely. The mermaid painting [Surface Tension] over there, she’s female. I painted this at a time in my life when everything seemed to fall apart. My parents got divorced, and my husband and I almost divorced, and I was really sick. I had back problems from repetitive-use injuries. And, I mean, it was bad, and there were lots of other things at play, and I had to learn how to swim. I thought, “I can’t let life bulldoze me over like this. I’m going to drown if I don’t grow a pair of fins or something right now and learn how to swim.” So I painted this angst-ridden mermaid growing fins, and she’s fighting with them. Each of the scales has little smiley faces on them to illustrate the benevolence of learning how to grow up and take care of yourself. To me that is not something that is applicable to just women; it’s anybody growing up and coming into the tough waters of life. I’m dealing with emotion, which I think more than just women can relate to. In fact, I know so, because I have a lot of male fans and followers who will write me, and they’ll say, “Thank you. This painting really spoke to me. I’ve been there. I know what it means to feel this.” That’s really great, when I’m really able to transcend and leap out of gender.

How are you intentionally challenging yourself in the studio right now?

My m.o. is that every single painting that I start needs to have something new that challenges me and scares me. For example, I did a painting of my friend’s husband [Forgiveness], and I painted him as a genie, and I stabbed the painting in the back. That’s supposed to be an act of forgiveness, allowing yourself to feel anger. And I had a lot of anger with the male figures in my life, and I realized that they’re just mortal men. They’re not wish-granters. They’re not genies. So I had a cathartic process of punching holes in the canvas [as though] with a knife, relieving and acknowledging my anger and my grief and allowing myself to come into a space of forgiveness. That was really scary for me. So each of the paintings has to do something that’s new and exciting or scary.

A lot of your work strikes me as very funny and humorous in a self-aware way. What is humor for you as a device? What do you hope to bring through with the humorous elements in your work?

When I was a kid I loved comedy, and I wanted to be a stand-up comedian. I don’t know if I’m ever going to do that, but I’ve found that it is a very important tool of mine, making people laugh. My mom deals with chronic pain, and my ability to make her laugh was very important because it sort of eased her pain, and her ability to be a mother was better because of it. I’ve found that humor is a very universal and disarming way of talking about very tough stuff. I didn’t make it onto the stage of any stand-up comedy place, so I decided I wanted to use it in my work. I gotta use some kind of sense of humor here. I actually got a little bit of criticism from a woman who told me it’s not my responsibility to make people laugh at my pain—or the pain of women. And I remember that.

Do you feel that you’re using humor as a way to make your content more digestible?

Yes. Humor is a very interesting thing. Laughter can be “you’re laughing with me” or “you’re laughing at me,” and the best way I’ve heard comedy or laughter defined is as the relief of tension. It disarms. Once you can make someone laugh, they’re more open to what you have to say. It’s a very powerful tool, and in that way, I think she thought I was trying to make a joke and make it funny or trivialize it. And that’s not what I was doing. I work a lot with satire, and it can be kind of dark, but it also does make the work more digestible for people.

Do you ever have the desire to move beyond relying on humor in that way?

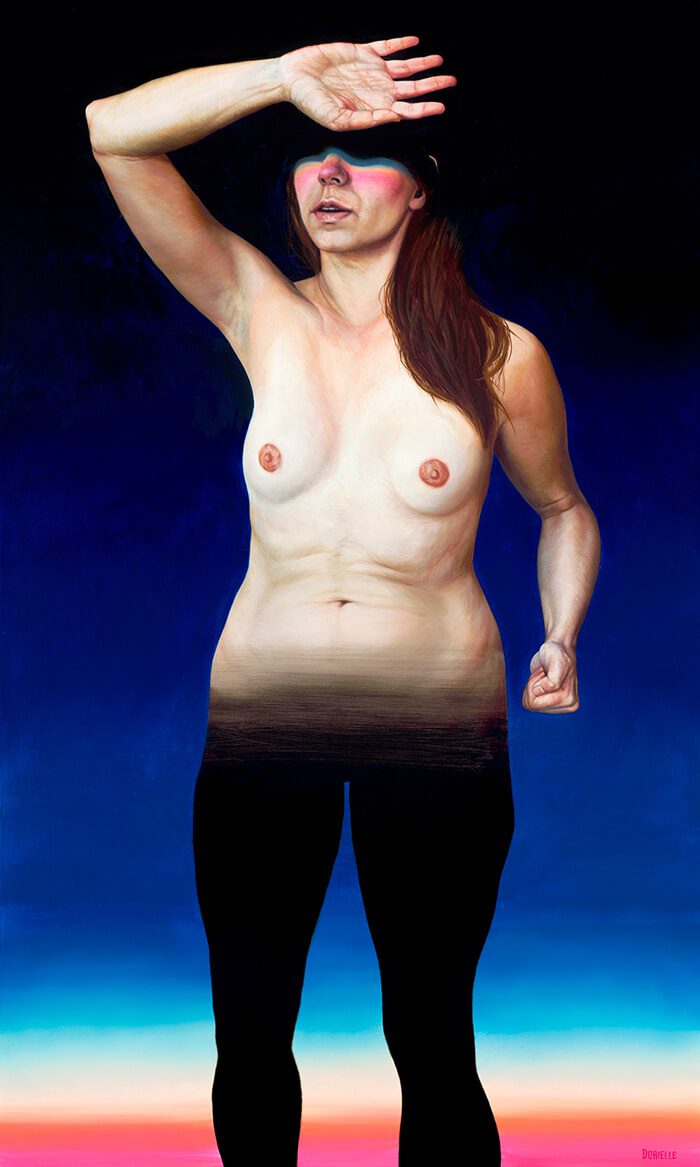

I do. I’ve already moved out of humor in some of my works, but for me, humor allows me to wade out into deep water, and the humor is like my floaties or my buoy. It helps me to get into the work but not get too heavy. It also serves as visual juxtaposition, which is an important tool when creating good writing or good acting. If I compare something very difficult with something lighthearted, it somehow disarms it, and it can create understanding. I still like to be able to laugh at my work or laugh with my work. That’s important to me when I’m here by myself; it keeps me coming back and keeps me doing the work. Having said that, I am moving into works that aren’t really terribly funny or tongue-in-cheek. Like the painting After a Long Night: it’s just basically me standing there, slowly being illuminated, as if I was on the dark side of a planet that’s turning, and eventually the sun is coming up. When my health was really bad a few years ago and all that shit hit the fan, I fell into a really dark place. I was diagnosed with severe PTSD and chronic situational depression. And I was being treated for all of that. I had a lot of friends and family come out and say, “You just gotta stick with it. You’re gonna get better. You’re healing.” But it just felt like the world was spinning and it was dark. Eventually I started to see more and more light, and it was like I was becoming more illuminated. So in this painting, she’s got her hand over her face, because she hasn’t quite realized that the light is coming back, but she’s about to move into a new era. I was gonna put little stars with little happy faces and stuff, but really the only person I trust with my ideas is my little sister. I told her about that, and she said, “No, Dorielle. I think in this case that would cheapen the work, and I think the black serves as a more powerful tool than black with stars, because the stars aren’t actually illuminating the concept. And the concept is that you’re coming out of darkness.”