UNM Art Museum, Albuquerque

Oct 28, 2016 – March 11, 2017

Worldwide, we take a lot of pictures—over one trillion per year, in fact. Many of them, snapped with smartphone cameras, earn only seconds of our attention before being deleted or forgotten, replaced by the next “grammable” moment. Whether you believe that photo sharing trends are popularizing photography or destroying it, it is clear that this glut of amateur picture taking is changing our relationship with images. From social media sites to digital frames, new technologies aimed at making our images more immediately available may also threaten to devalue them. Arguing against this casual consumption of pictures is a new exhibition at the University of New Mexico Art Museum, which instead highlights the rewards gained from a more mindful study of actual, physical photographs. On view now through March 11, 2017, Stories from the Camera features works from the museum’s phenomenal collection. The selected works are the visual iteration of a recent, and similarly titled, publication, Stories from the Camera: Reflections on the Photograph (2015, University of New Mexico Press). Both the exhibition and the book were conceived by former UNM Art Museum Curator of Prints and Photographs, Michele M. Penhall, and are as much a celebration of the medium as of the symbiotic relationship between the museum, its collection, and the university community.

As one of the first universities in the nation to acknowledge the academic and artistic value of photography, offering both an MFA in photography and a PhD in the history of photography, UNM earned a reputation as one of the top schools for studying the medium. This reputation has garnered an impressive list of faculty and alumni over the program’s nearly sixty-year history, and it is this enviable resource that Penhall turned to when developing the project. The book contains twenty-one essays by artists and scholars, each invited to write about works that have particularly resonated with them. Their individual accounts serve as the basis for the exhibition, and this personal—rather than academic—curatorial approach makes the exhibition feel warmly nostalgic and intimate.

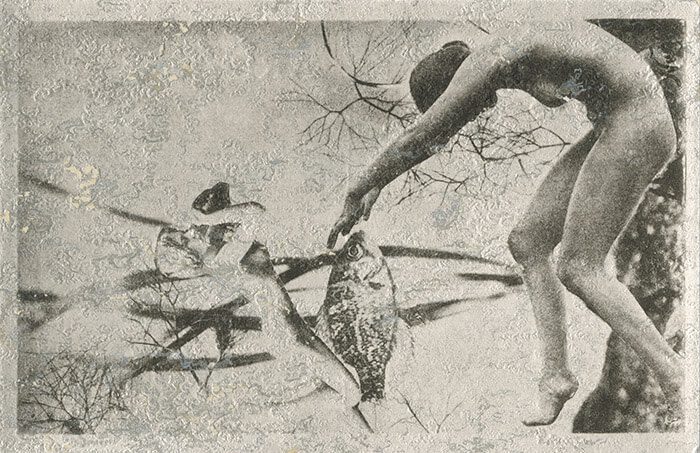

While the text aids in telling the history of the displayed images, the exhibition stands strongly on its own as a visual manifestation of the text’s secondary premise: regard for the photograph as a physical object, as well as an image. In her introductory essay for the exhibition’s corresponding publication, Penhall writes of the value of experiencing photographs outside the dimensions of a screen or textbook, “the size and scale of a work, the particular characteristics and nuances of canvas, paper, or metal, and sometimes even the faint scent of an object, are conveyed only in person.” This statement, which so eloquently describes the character of the printed photograph, is reinforced by the physicality and dimensionality of many of the works on display. Betty Hahn’s Greenhouse Portrait (Bea Nettles) (1973), printed on fabric, literally pierces through the picture plane with embroidered stitches. On view in the center of the gallery are richly textured, pocket-sized nineteenth century portrait daguerreotypes, encircled with golden fillets and nestled in red velvet-lined cases. One of the more unique pieces in the exhibition is a series of postcards created by a veritable “who’s who” of the surrealist art movement. This curious collection of shiny silver collotypes is a delight to examine, as one connects the bizarre images to the list of their famous creators including Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, and André Breton.

After being exposed to a daily deluge of snapshots, it is a pleasure to feel so intimately engaged with images and to remember why we take pictures.

Other well-known and well-loved works are on display that will be—and should be—a draw for visitors. Alfred Stieglitz’s celebrated image, The Steerage (1907), one of Eadweard Muybridge’s groundbreaking studies of a horse in motion (1884-1886), and a selection from Carrie Mae Weems’s seminal series, From the Kitchen Table (1990), are just a few examples of the pioneering images sharing space with lesser-known, but no less captivating, works in the gallery. Experiencing their material details is a compelling enough argument to visit the Stories from the Camera exhibition, but perhaps more so, after being exposed to a daily deluge of snapshots, it is a pleasure to feel so intimately engaged with images and to remember why we take pictures. The good ones invite us to pause, ask questions, and investigate, as if unpacking a mystery—and through our own wondering, create new stories of our own.