In this essay, Tyler Stallings pens a letter to the University of Arizona Museum of Art regarding Willem de Kooning’s stolen painting Woman-Ochre.

To the Board of Trustees and Director of the University of Arizona Museum of Art,

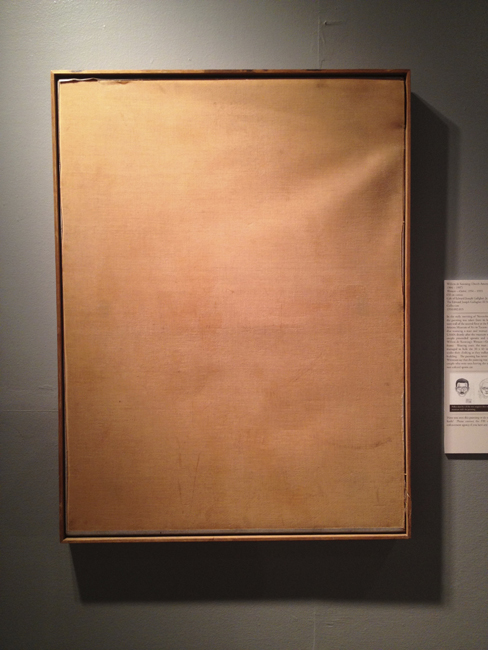

I am writing to share with you my deep disappointment and frustration regarding Willem de Kooning’s painting, Woman-Ochre (1954-55). As you know, this iconic masterpiece was stolen from the University of Arizona Museum of Art in 1985 by an innocuous couple—a man and woman who entered one morning, cut the painting off its stretcher bars, and exited with it under their coats. It remained missing for a span of thirty years until it was recovered in 2017.

Like many others, I had followed the story, wondering if the painting would ever resurface. But now that the painting—restored and repaired after a lengthy process—is finally back on view at the museum, I’m overcome with a sense of loss and sadness.

You see, I had become very attached to the empty frame that had hung on the museum’s wall for so long, where Woman-Ochre used to be. I was drawn to its elegant lines and the way it seemed to command attention even in its emptiness. I saw the empty frame for what it was—something unique from all the other works in the museum: an absence of image.

Contemplating the empty frame where Woman-Ochre once hung, my mind drifted to another famous work of art: Robert Rauschenberg’s collaboration with de Kooning. In 1953, Rauschenberg approached de Kooning and asked for a drawing to erase. After much persuasion, de Kooning finally gave Rauschenberg a drawing of one of his women, not unlike the figure in Woman-Ochre.

The erasure took Rauschenberg over a month to complete, but eventually, he succeeded in erasing all traces of de Kooning’s drawing, leaving only a blank sheet of paper behind.

Thinking of the Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953), the empty frame around the missing de Kooning took on a new significance. Just like the blank sheet of paper that Rauschenberg had created by erasing de Kooning’s drawing, the empty frame at the museum now had a history of its own—a history of longing and loss.

The frame became a work of art in its own right—a testament to the enduring power of absence and imagination. It was an invitation to imagine, to dream, to participate in the creative process.

But now that Woman-Ochre has been returned to the museum, the empty frame is no longer empty. It is no longer a blank page waiting to be filled.

Of course, the theft of Woman-Ochre was a tragedy—a selfish act of desire (on the part of the thieves) against a work of art. When the day came to return it, I was overjoyed—until I realized that it meant the end of my own personal connection to the empty frame on what I had come to think of as “my wall.”

Maybe I should consider becoming an art thief myself, or maybe start a museum of empty frames, so that people can fill them in with their imaginations? As you can see, I miss the possibilities of beauty coming from the power of absence and loss.

Sincerely,

An Art Lover