Species In Peril Along the Rio Grande

September 28–December 28, 2019

516 Arts, Albuquerque

Silhouettes of small fish swim out from the frame of a silver-white screen. I watch as they emerge from the white and then dive back into it, as into and out of water. After some time, they morph in my mind’s eye, become tiny airplanes, crisscrossing a white void above the outline of a river that is drawn and erased and redrawn in the center of the screen.

The river—a hint of a river, like the faint line on an atlas—is the Rio Grande. The fish—or are they ghosts?—is the Rio Grande silvery minnow. The work’s makers, Jennifer Owen-White and Mary Tsiongas, are two of twenty-three artists featured at 516 Arts for Species in Peril Along the Rio Grande. The exhibition is part of a regional collaboration featuring talks, exhibitions, and performances throughout the southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico, all focused on local examples of the mass species loss that continues to be documented at a global scale.

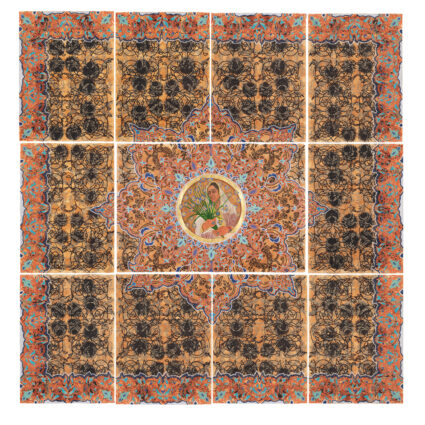

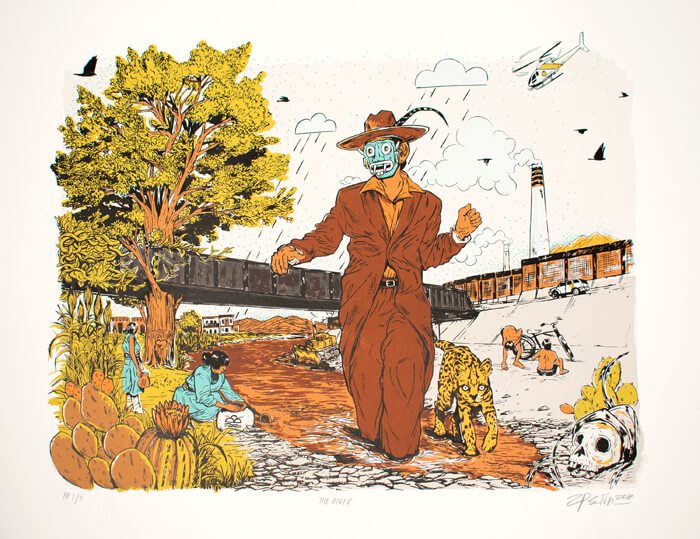

Many of the works here study a single threatened species. There are great, mythic creatures—Cannupa Hanska Luger’s majestic buffalo, Catalina Delgado-Trunk’s papel picado jaguars, Jaque Fragua’s Wolf Xing (2019)—and there are smaller, yet still familiar players, like the beaver whose skull floats ominously above a gorge in Nina Elder’s Interrupted Ecosystem: Beaver and Rivers(2019).

Then there are the invisible.

Across the room from the shadowy minnows, a long list of microbial species is projected on the wall. Part of an installation by Agnes Chavez, the list was compiled through the DNA sequencing of a water sample collected in northern New Mexico, representing the microbiome of the river. It’s a reminder that the life of the river eludes our senses, is beyond us even as we feign to master it.

Its Vitality Comes Through Fluctuation (2019) speaks to another aspect of the river that, for me and many New Mexicans, is purely conceptual: the ecological role of flooding, needed for cottonwood seedlings to grow into new trees. (The Rio Grande’s flow has been controlled by humans since the 1940s, when the aging cottonwoods of today’s imperiled bosque were born.) Created by Kaitlyn Bryson and Hollis Moore, the installation is a sort of diorama of riparian habitat. Animal tracks are sewn into handmade cottonwood paper embedded with native seeds. On my first visit, the pale green sprouts were barely perceptible. On my second, they are taller, thicker, and joined by leafier seedlings. I returned for this—to see organic change unfold within the confines of the gallery—but what pleases me now, as I bend over the grow lights, is the surprising scent of dirt.

Last year, I backpacked through the Weminuche Wilderness in southern Colorado, setting off from a trailhead within sight of the Rio Grande Reservoir, held in by the oldest of the many dams that fragment and domesticate the Rio Grande. It was September in another drought year, and the water was so low that the reservoir resembled a meadow. The aspens were at the peak of their blaze. A mile or so in, the yellows and oranges gave way to black and brown. The landscape was a vast graveyard for Engelmann spruce, hillsides and aisles of deadwood, whole forests lost to the spruce beetle to which trees are more vulnerable in times of drought. Wildlife was sparse in these grim stands.

I think about that hike as I eye some dead spruce in Michael Berman’s Binary Codex – The Habitat (2019). For anyone who has traveled much of the river, Berman’s photographs are like family snapshots: many scenes are familiar, some are distressing, some look like accidents, and so many are nearly forgotten or almost missed. The series, printed in carbon pigment on three tall sheets of kozo washi housed in rectangular frames, follows the Rio Grande from the Gulf to the headwaters. I squint to read the no trespassing signs, see the yucca, the lonely old cottonwood. A pair of mannequin legs hangs near an abandoned bag of clothing. There are shots of the border wall, blocking the migration of land-bound animals. In one photo, a notice of sea turtle nesting foregrounds a fenced lot full of semi-trucks. The ordering of the photos suggests a timeline, but then again, there is looping, fluctuation. I take it in in bits and pieces. I am part of this fragmentation.

I come home, drink a glass of water from the tap. Later, I read in the catalogue that ninety-five percent of the Rio Grande’s annual flow goes to municipal water and agriculture. It’s not wild beauty, I realize, but an elaborate web of engineering projects that most intimately connects us.