Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

February 3–April 23, 2018

Brooklyn Museum, New York

Sept. 7, 2018–Feb. 3, 2019

In a recent interview in Artforum, the artist Howardena Pindell recalls her first efforts toward protesting the oppressive and exclusionary practices of art institutions in the 1970s: “Because I was a curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, I needed to remain anonymous, so I would just send little notes of complaint to magazines, to museum boards, and to the city signed ‘The Black Hornet.’ I have never told anyone about these, and I had almost forgotten that period. I was frustrated because I was so voiceless.” As an African American woman, part of Pindell’s frustration stemmed from pervasive omissions of women and people of color—from exhibitions, from museum collections, and from the critical discourse around contemporary art. Although some black artists did receive recognition, their inclusion in that discourse often served a version of contemporary art that did not take into account the many creative, intellectual, and political concerns of the African American artistic communities thriving during the 1960s and 1970s.

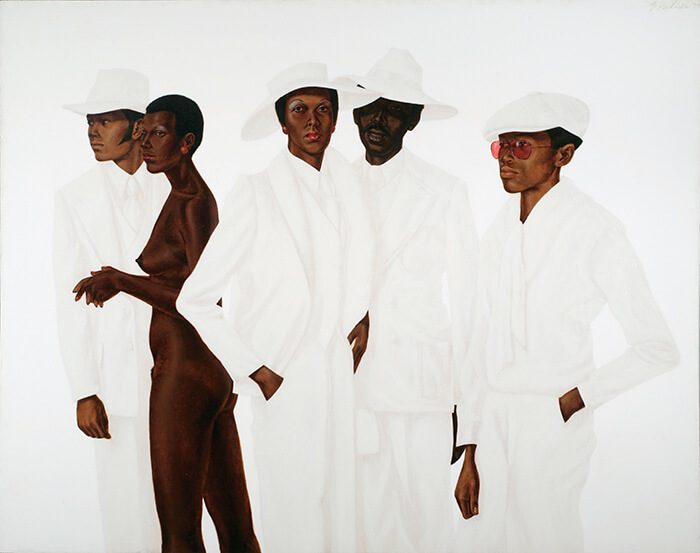

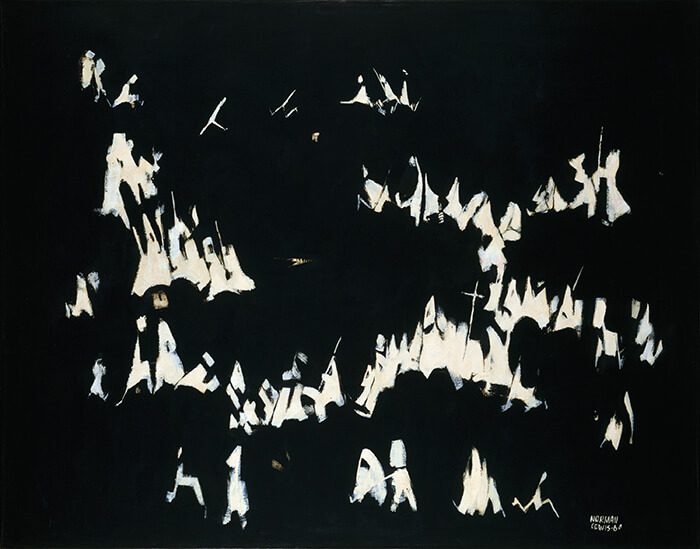

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power creates a space for an array of African American artists who were deeply engaged in the aesthetic and social justice issues that emerged from the civil rights and Black Power movements. Collectives like Spiral and AfriCOBRA mined African American history and culture and incorporated contemporary techniques of painting, printmaking, and fashion design to create a unique iconography for this vital political era. Norman Lewis’s painting America the Beautiful (1960) appears to be a typical mid-twentieth-century abstract, gestural painting, but on closer inspection, the expressive white brushstrokes crystallize into the familiar hoods and crosses of the Ku Klux Klan. Jae Jarrell’s Revolutionary Suit (1969) adopts the mod style of the 1960s and incorporates a woven and colorful ammunition belt across the suit’s shoulder, with one crucial difference: the belt holds pastel chalks, not bullets. The paintings of Barkley L. Hendricks represent and celebrate the black body, from the nearly life-size painting of a group of figures dressed in white to contrast a single nude in What’s Going On (1974), to a portrait of Black Panther founder Bobby Seale, to a fully frontal nude self-portrait.

Not all of the works in Soul of a Nation overtly address the Black Power movement or civil rights. In a gallery devoted to abstraction, a monumental, prismatic swath of stained canvas hangs in draped folds attached directly to an entire wall. With Carousel Change (1970), Sam Gilliam questions the essential nature of both painting and sculpture, thus engaging in a crucial debate that raged in 1960s formalist circles. As such, Gilliam’s explorations rival the formal breakthroughs of Frank Stella’s shaped canvases of the 1960s. But to compare Gilliam to Stella would be to miss the point; Soul of a Nation accesses a history completely autonomous from its white counterpart. Within this context, even artists who will likely be familiar to most viewers, such as Faith Ringgold, Bettye Saar, David Hammons, and Pindell, engage in a broader narrative of empowerment and the preservation of a history that was constantly under attack by political and artistic institutions during the 1960s and 1970s.